The YouTube channel There I Ruined It creates new versions of songs using AI-generated voices. For Dustin Ballard, the channel’s creator, the point is to “lovingly destroy your favorite songs.” Take the example above. Here, an AI version of Johnny Cash’s voice sings the lyrics of Aqua’s “Barbie Girl,” set to the music of Cash’s “Folsom Prison Blues.” Recently, Ballard explained his approach to Business Insider:

My process for these is a little different than most people. I first record the vocals myself so that I can do my best imitation of the cadence of the original singer. Then I use one of their own songs (like ‘Folsom Prison Blues’ rather than the original ‘Barbie Girl’ music) to add to the illusion that this is a ‘real’ song in the artist’s catalog, though clearly all done in jest. Finally, I use an AI voice model trained on snippets of the original artist’s singing to transform my voice into theirs. I have a guy in Argentina I often call upon for this training (although the Johnny Cash one already existed).

If you head over to There I Ruined It, you can hear other AI creations: Hank Williams sings “Straight Outta Compton,” Louis Armstrong sings Flo Rida’s “Low,” Frank Sinatra sings Lil Jon’s “Get Low” and more.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content

Humanity has few fascinations as enduring as that with apocalypse. We’ve been telling ourselves stories of civilization’s destruction as long as we’ve had civilization to destroy. But those stories haven’t all been the same: each era envisions the end of the world in a way that reflects its own immediate preoccupations. In the mid nineteen-eighties, nothing inspired preoccupations quite so immediate as the prospect of sudden nuclear holocaust. The mounting public anxiety brought large audiences to such major aftermath-dramatizing “television events” as The Day After in the United States and the even more harrowing Threads in the United Kingdom.

“As a youngster growing up in the nineteen-eighties in a tiny village in the heart of the Cotswolds, I can attest to the fact that no part of the country, however remote and bucolic, was impervious to the threat of the Cold War escalating into a full-blown nuclear conflict,” writes Neil Mitchell at the British Film Institute.

“Popular culture was awash with nuclear war-themed films, comic strips, songs and novels.” This torrent included the artist-writer Raymond Briggs’ When the Wind Blows, a graphic novel about an elderly rural couple who survive a catastrophic strike on England. Jim and Hilda’s optimism and willingness to follow government instructions prove to be no match for nuclear winter, and however inexorable their fate, they manage not to see it right up until the end comes.

In 1986, When the Wind Blows was adapted into a feature film, directed by American animator Jimmy Murakami. Among its distinctive aesthetic choices is the combination of traditional cel animation for the characters with photographed miniatures for the backgrounds, as well as the commissioning of soundtrack music from the likes of Roger Waters, David Bowie, and Genesis — proper English rockers for a proper English production. If the adaptation of When the Wind Blows is less widely known today than other nuclear-apocalypse movies, that may owe to its sheer cultural specificity. It would be difficult to pick the movie’s most English scene, but a particularly strong contender is the one in which Hilda reminisces about how “it was nice in the war, really: the shelters, the blackout, the cups of tea.”

“The couple are fruitlessly nostalgic for the Blitz spirit of the Second World War, convinced the government-issued Protect and Survive pamphlets are worth the paper they’re printed on, and blindly under the assumption that there can be a winner in a nuclear war,” writes Mitchell. “These sweet, unassuming retirees represent an ailing, rose-tinted worldview and way of life that’s woefully unprepared for the magnitude of devastation wrought by the bomb.” You can see further analysis of the film’s art and worldview in the video at the top of the post from animation-focused Youtube channel Steve Reviews. In the event, humanity survived the long showdown of the Cold War, losing none of our penchant for apocalyptic fantasy as a result. However compulsively we imagine the end of the world today, will any of our visions prove as memorable as When the Wind Blows?

Related content:

Protect and Survive: 1970s British Instructional Films on How to Live Through a Nuclear Attack

The Night Ed Sullivan Scared a Nation with the Apocalyptic Animated Short, A Short Vision (1956)

Duck and Cover: The 1950s Film That Taught Millions of Schoolchildren How to Survive a Nuclear Bomb

How a Clean, Tidy Home Can Help You Survive the Atomic Bomb: A Cold War Film from 1954

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

The Brooklyn Bridge ignites the passions of tourists and locals alike.

For every 10,000 visitors who pause in its bike lanes to snap selfies, there’s an alum of nearby PS 261 who celebrated its birthday with a song that mentions the fates of its engineers John and Washington Roebling to the tune of I’ve Been Working on the Railroad.

(A sample chorus: Caisson’s disease! Caissons disease! Caisson’s disease is really bad!)

Native son Adam Suerte of Brooklyn Tattoo estimates that he inks its likeness on a half dozen customers per month. (A temporary option is available for those with commitment issues…)

In 1886, a hustler named Steve Brodie claimed to have survived a jump off of it, a tale propagated by Bugs Bunny.

We watch movies at its feet and draw attention to causes by marching across it.

It continues to mesmerize artists, poets, filmmakers and photographers.

But, as architect Michael Wyetzner makes clear in his most recent video for Architectural Digest, it’s not the only bridge in New York City.

Also, despite what you may have heard, it’s not for sale.

Understandably, the hybrid cable-stayed/suspension superstar connecting Brooklyn to lower Manhattan takes the lead in Wyetzner’s coverage of five bridges that have had an enormous impact on the development of a city whose five boroughs were once traversable solely by ferry.

The other notable players:

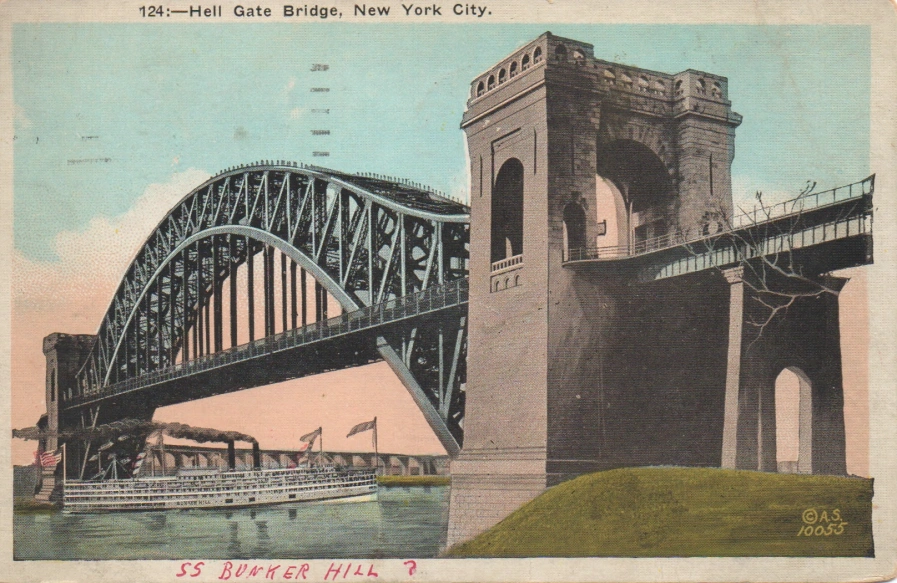

The Hell Gate Bridge – a feat of WWI-era railroad engineering connecting Queens to Randall’s and Wards Island over a particularly perilous stretch of waterway, it was once the longest steel arch bridge in the world.

In his 1921 book New York: The Great Metropolis, painter Peter Marcus noted that “if laid over Manhattan it would reach from Wanamaker’s store at Eighth Street, to One Hundred and Twenty-fifth Street.”

Macomb’s Dam Bridge, a low lying swing bridge whose center portion pivots to accommodate boat traffic on the Harlem River. When construction began in late 1890, the New York Times gushed that it would be a “street built in mid-air” between the Bronx and Washington Heights in upper Manhattan:

It is hardly enough to say of it that it will be the greatest piece of engineering of the kind in the world. Nothing like it has ever been attempted.

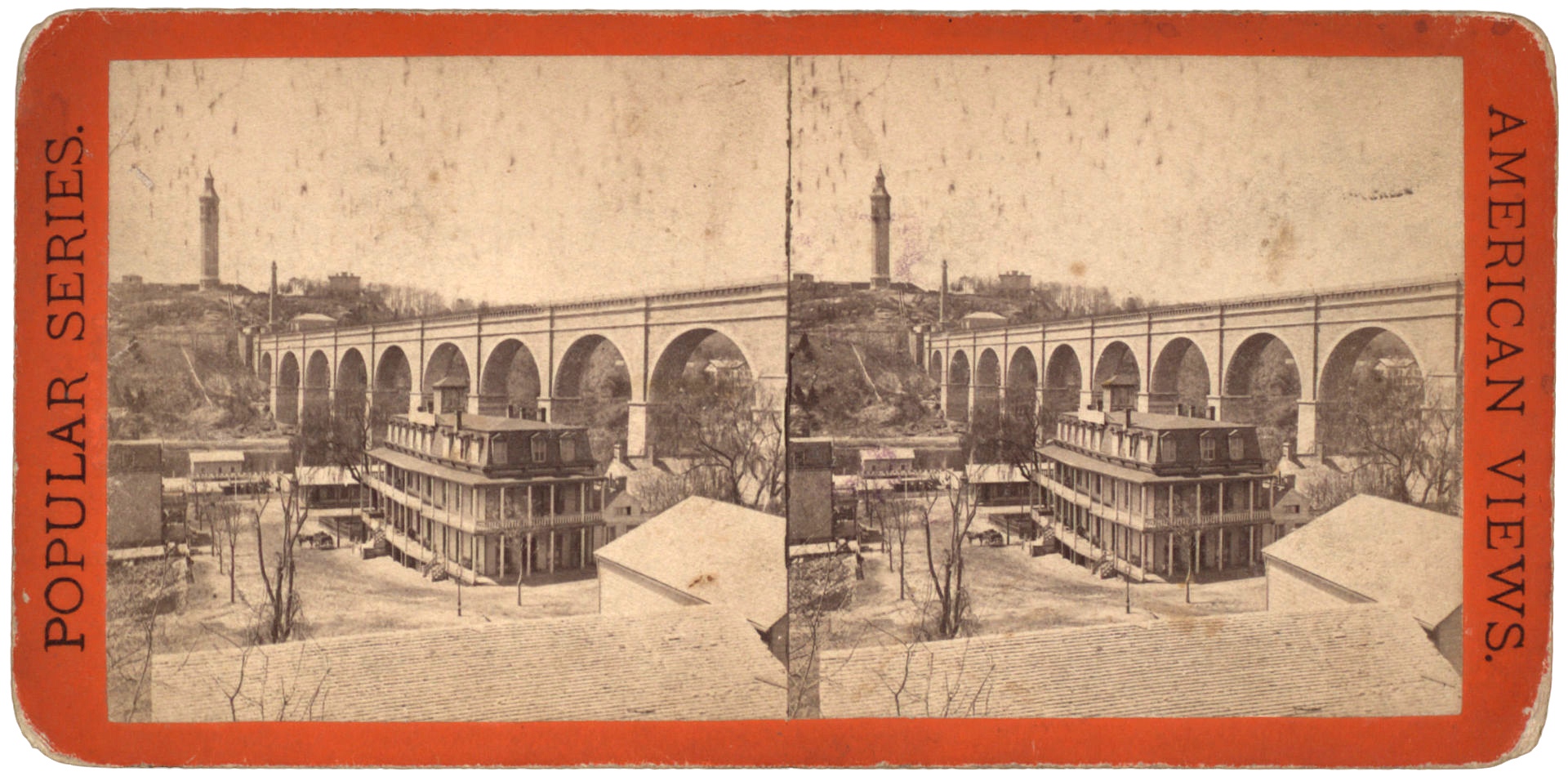

The High Bridge – Originally part of the Croton Aqueduct, it is technically the oldest surviving bridge in the city, as well as a community-led preservation campaign success story. Having languished in the latter part of the 20th century, it is now a beautiful pedestrian bridge whose killer views can be enjoyed without the hassle of Brooklyn Bridge-sized crowds.

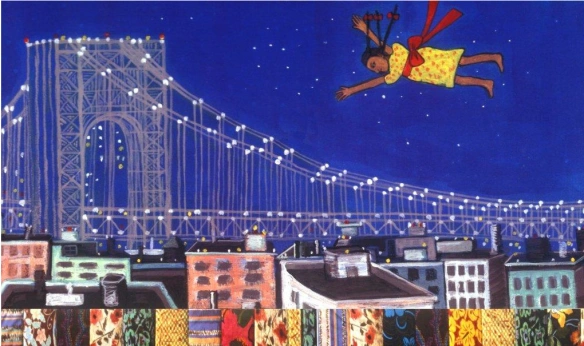

The George Washington Bridge – a major money maker for the Port Authority, it’s not only the world’s busiest bridge, it puts a lot of the bridge in “bridge and tunnel crowd” by connecting Manhattan to New Jersey.

Architecture buffs can geek out on the Concrete Industry Board Award-winning bus station and storied Little Red Lighthouse in its shadow.

The GWB’s most ardent fan has got to be artist Faith Ringgold, who immortalized it in her Tar Beach story quilt and related children’s book:

I never want to be more than three minutes from the George. I could always see it as I grew up. That bridge has been in my life for as long as I can remember. As a kid, I could walk across it anytime I wanted. I love to see it sparkling at night. I moved to New Jersey, and I’m still next to it.

Wyetzner, whose architectural round up shoehorns in a lot of interesting information about public health, economics, transportation, labor practice and New York City history, is actively courting viewers to suggest bridges for a sequel.

We’ll throw our weight behind the Manhattan, the Williamsburg, the Queensboro, the Verrazzano, and the admittedly dark horse 103rd Street Footbridge.

You?

Related Content

How the Brooklyn Bridge Was Built: The Story of One of the Greatest Engineering Feats in History

A Mesmerizing Trip Across the Brooklyn Bridge: Watch Footage from 1899

See New York City in the 1930s and Now: A Side-by-Side Comparison of the Same Streets & Landmarks

An Online Gallery of Over 900,000 Wonderful Photos of Historic New York City

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

There may not yet be civilization on the moon, but that doesn’t mean there’s no culture up there. We’ve previously featured the tiny ceramic tile, smuggled onto the Apollo 12 lunar lander, that bears art by the likes of Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol. “Fallen Astronaut, an aluminum sculpture by the Belgian artist Paul van Hoeydonck, was left on the lunar surface by the Apollo 15 crew in 1971,” writes the New York Times‘ J. D. Biersdorfer. “The Arch Mission Foundation has sent Isaac Asimov’s Foundation trilogy and millions of Lunar Library pages into space,” and artists like Jeff Koons and Sacha Jafri are among the artists currently aiming to install their own work on the moon’s surface.

The Lunar Codex has grander ambitions, having assembled works from “over 30,000 artists, writers, musicians, and filmmakers, from 158 countries, in four time capsules launched to the moon.” You can browse their contents at the project’s official web site, which breaks it all down into not just eight “galleries” of visual art, but also sections dedicated to film, television, music, and poetry, among other forms and media. There’s even a section for books and novels (as well as another, oddly, for novels and books), which includes a large number of curious titles to represent the achievements of human civilization: Kamikaze Kangaroos, Goofy Newfies, Don’t Taco ‘Bout Murder, In Bed with Her Millionaire Foe.

Also among all these books, stored on either digital memory cards or a nickel-based medium called NanoFiche, is The Zoo at the End of the World by one Samuel Peralta, who also happens to be the mastermind of the Lunar Codex project. “A semiretired physicist and author in Canada with a love of the arts and sciences,” Peralta has selected for preservation on the moon everything from “prints from war-torn Ukraine” to “more than 130 issues of PoetsArtists magazine” to images like “New American Gothic, by Ayana Ross, the winner of the 2021 Bennett Prize for women artists; Emerald Girl, a portrait in Lego bricks by Pauline Aubey; and the aptly titled New Moon, a 1980 serigraph by Alex Colville.”

All the work to be placed on the moon through the Lunar Codex was created by artists who are now active, or have been active in the past decade or two. As such, it reflects a particular moment in the cultural history of humanity, constituting what Peralta calls “a message in the bottle for the future that during this time of war, pandemic and economic upheaval people still found time to create beauty.” They also found time to create podcasts, as will be evidenced by the inclusion of a quarter-century-long archive of Grace Cavalieri’s interview show The Poet and the Poem, which has reached a new audience in recent years through that relatively new format — one that, to future generations of spacefarers making a stop on the moon, will offer as good a representation as any of life on Earth in the twenty-first century.

Related content:

There’s a Tiny Art Museum on the Moon That Features the Art of Andy Warhol & Robert Rauschenberg

NASA Puts Online a Big Collection of Space Sounds, and They’re Free to Download and Use

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Too often those in power lump thousands of years of Middle Eastern religion and culture into monolithic entities to be feared or persecuted. But at least one government institution is doing exactly the opposite. For Nowruz, the Persian New Year, the Library of Congress has released a digital collection of its rare Persian-language manuscripts, an archive spanning 700 years. This free resource opens windows on diverse religious, national, linguistic, and cultural traditions, most, but not all, Islamic, yet all different from each other in complex and striking ways.

“We nowadays are programmed to think Persia equates with Iran, but when you look at this it is a multiregional collection,” says a Library specialist in its African and Middle Eastern Division, Hirad Dinavari. “Many contributed to it. Some were Indian, some were Turkic, Central Asian.” The “deep, cosmopolitan archive,” as Atlas Obscura’s Jonathan Carey writes, consists of a relatively small number of manuscripts—only 155. That may not seem particularly significant given the enormity of some other online collections.

But its quality and variety mark it as especially valuable, representative of much larger bodies of work in the arts, sciences, religion, and philosophy, dating back to the 13th century and spanning regions from India to Central Asia and the Caucuses, “in addition to the native Persian speaking lands of Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan,” the LoC notes.

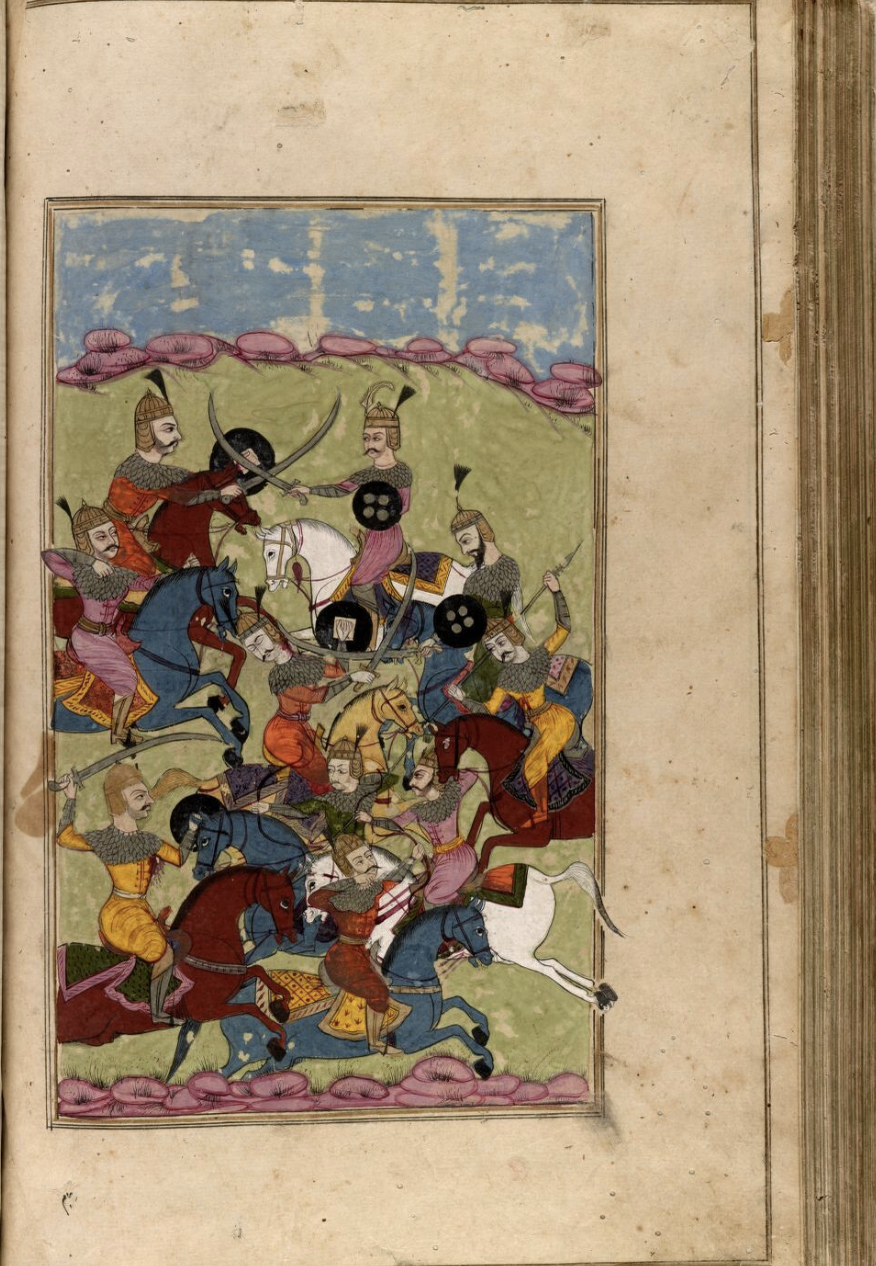

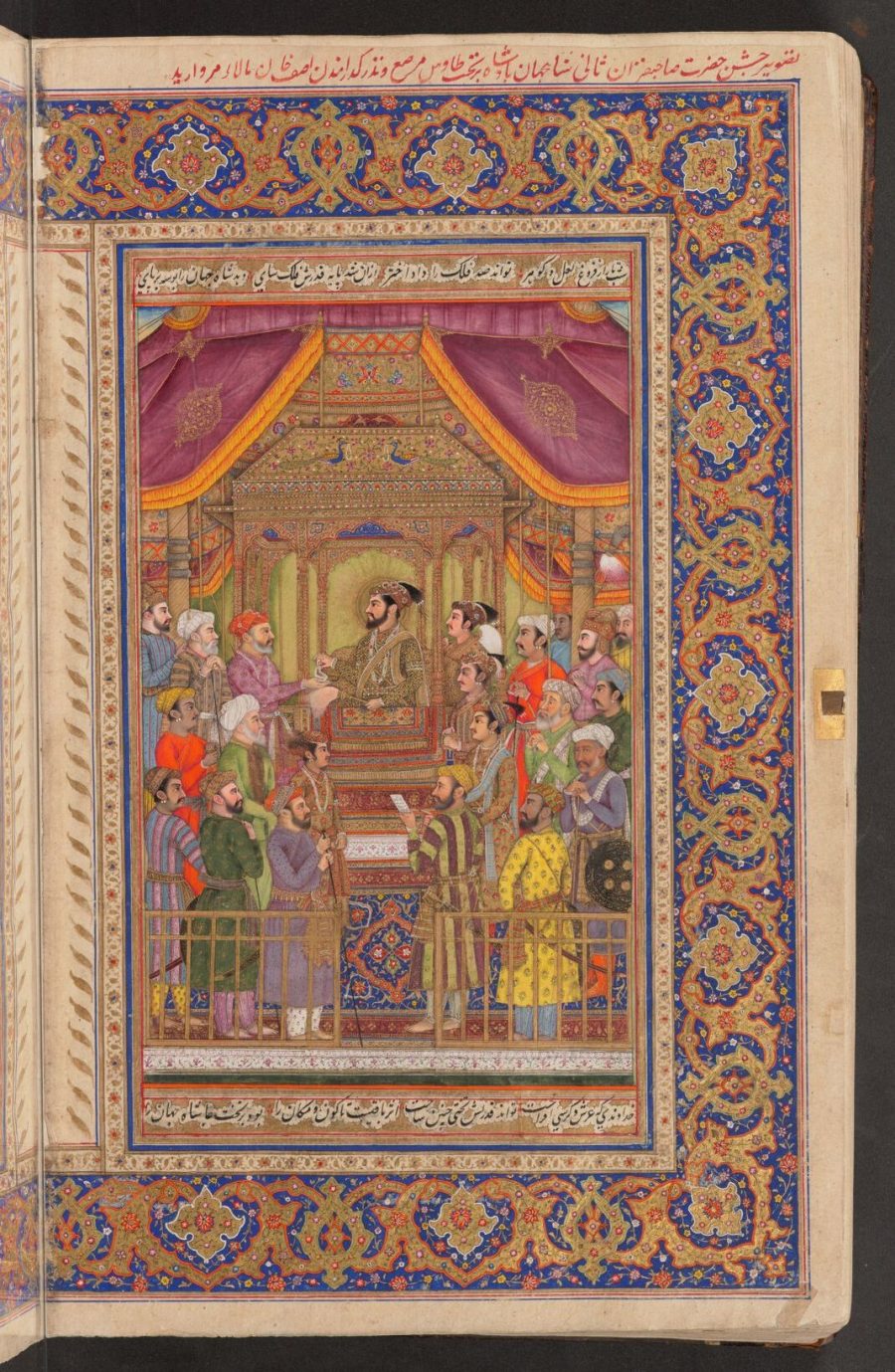

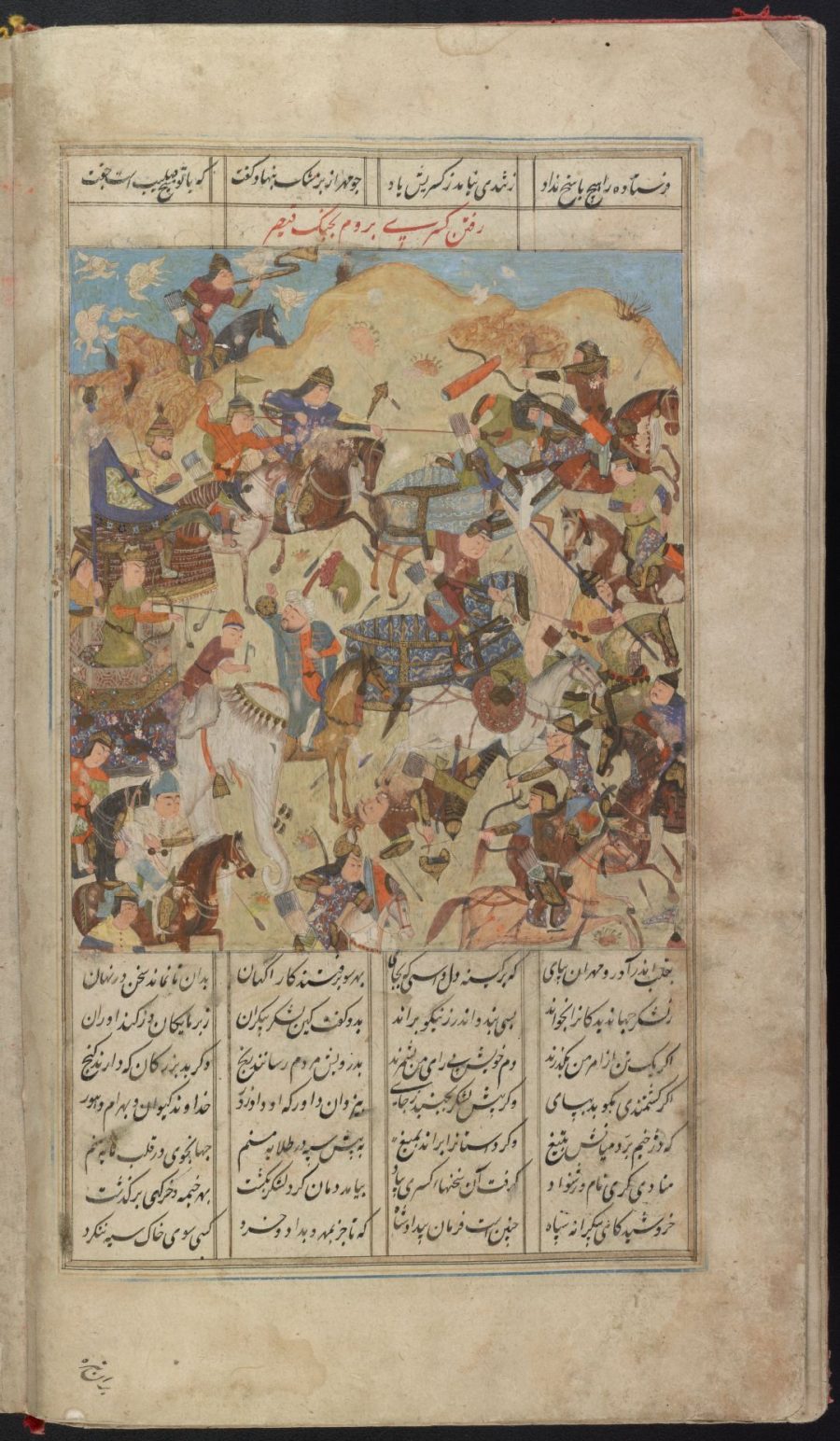

Prominently represented are works like the epic poem of pre-Islamic Persia, the Shahnamah, “likened to the Iliad or the Odyssey,” writes Carey, as well as “written accounts of the life of Shah Jahan, the 17th-century Mughal emperor who oversaw construction of the Taj Mahal.”

The Library points out the archive includes the “most beloved poems of the Persian poets Saadi, Hafez, Rumi and Jami, along with the works of the poet Nizami Ganjavi.” Some readers might be surprised at the pictorial opulence of so many Islamic texts, with their colorful, stylized battle scenes and groupings of human figures.

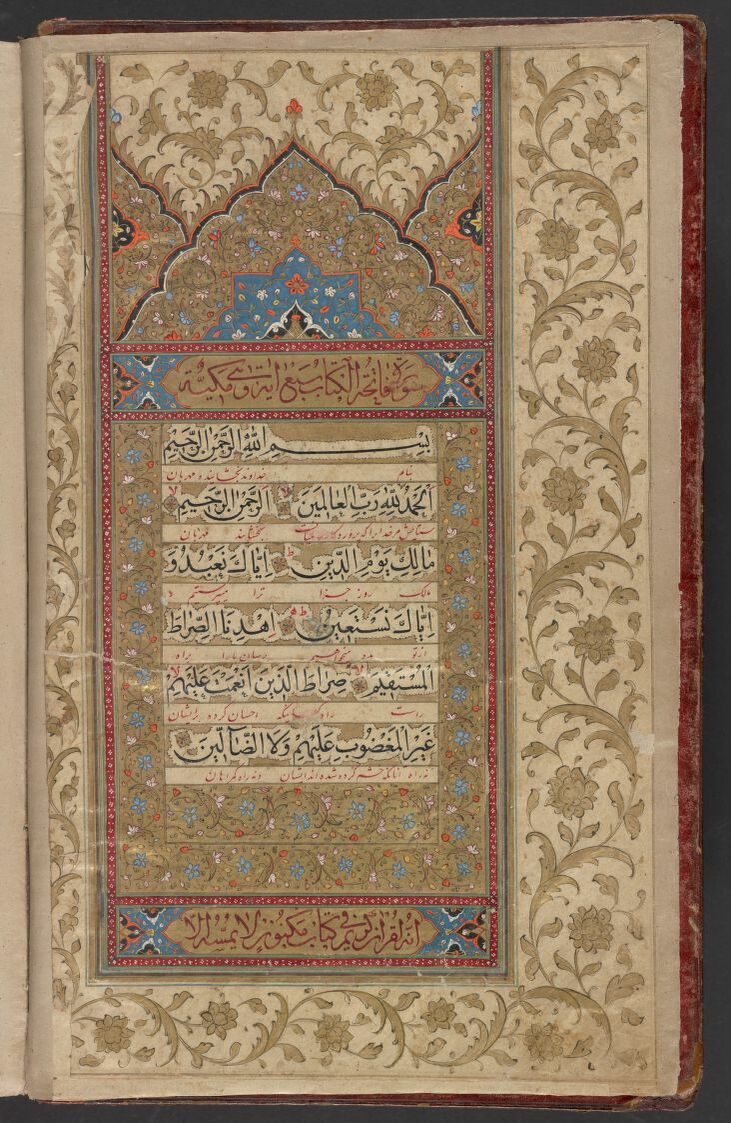

Islamic art is typically thought of as iconoclastic, but as in Christian Europe and North America, certain sects have fought others over this interpretation (including over depictions of the Prophet Mohammad). This is not to say that the iconoclasts deserve less attention. Much medieval and early modern Islamic art uses intricate patterns, designs, and calligraphy while scrupulously avoiding likenesses of humans and animals. It is deeply moving in its own way, rigorously detailed and passionately executed, full of mathematical and aesthetic ideas about shape, proportion, color, and line that have inspired artists around the world for centuries.

The page from a lavishly illuminated Qurʼān, above, circa 1708, offers such an example, written in Arabic with an interlinear Persian translation. There are religious texts from other faiths, like the Psalms in Hebrew with Persian translation, there are scientific texts and maps: the Rare Persian-Language Manuscript Collection covers a lot of historical ground, as has Persian language and culture “from the 10th century to the present,” the Library writes. Such a rich tradition deserves careful study and appreciation. Begin an education in Persian manuscript history here.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2019.

via Atlas Obscura

Related Content:

Discover the Persian 11th Century Canon of Medicine, “The Most Famous Medical Textbook Ever Written”

15,000 Colorful Images of Persian Manuscripts Now Online, Courtesy of the British Library

The Complex Geometry of Islamic Art & Design: A Short Introduction

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Brian Eno turned 75 years old this past spring, but if he has any thoughts of retirement, they haven’t slowed his creation of new art and music. Just last year he put out his latest solo album FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE, videos from whose songs we featured here on Open Culture. However compelling the official material released by Eno, the bodies of fan-made work it tends to inspire also merits exploration. Take French visual artist Thomas Blanchard’s short film “Emerald and Stone” above, which visualizes the eponymous track from Eno’s 2010 album Small Craft on a Milk Sea, a collaboration with Jon Hopkins and Leo Abrahams.

“Emerald and Stone,” which you’ll want to watch in full-screen mode, consists entirely of “riveting imagery built from a simple concoction of paint, soap and water.” So says Aeon, in praise of the film’s “ephemeral dreamworld of flowing music and visuals that’s easy to sink into.”

Its drifting, glittering bubbles have a planetary look, contributing to a visual aesthetic that suits the sonic one. Like many of the other compositions on Small Craft on a Milk Sea, “Emerald and Stone” will sound on some level familiar to listeners who only know Eno’s earlier work developing the genre of ambient music in the nineteen-seventies and eighties.

That same era witnessed — or rather, heard — the rise of “new age” music, which played up its associations with outer space, seas of tranquility, the movement of the heavenly bodies, and so on. Eno’s work was, at least in this particular sense, somewhat more down-to-earth: he called his breakout ambient album Music for Airports, after all, having created it with those utilitarian spaces in mind. Appropriately enough, Blanchard’s short for “Emerald and Stone” evokes the cosmos without departing from the fine grain of our own world, and appears abstract while having been made wholly from everyday materials. Eno himself would surely approve, having premised his own on not escaping reality, but placing it in a more interesting context.

via Aeon

Related content:

The Brian Eno Discography: Stream 29 Hours of Recordings by the Master of Ambient Music

Watch Videos for 10 Songs on Brian Eno’s Brand New Album, FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE

“Day of Light”: A Crowdsourced Film by Multimedia Genius Brian Eno

Brian Eno Explains the Origins of Ambient Music

Watch Brian Eno’s Experimental Film “The Ship,” Made with Artificial Intelligence

Brian Eno on the Loss of Humanity in Modern Music

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

?si=Kq5T7I10zGKJa-bE

These days, psychedelic research is experiencing a renaissance of sorts. And Matt Johnson, a professor of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins, is leading the way. One of “the world’s most published scientists on the human effects of psychedelics,” his research focuses on “unraveling the scientific underpinnings of psychedelic substances, moving beyond their historical and cultural context to shed light on their role in modern therapeutic applications.” Like some other researchers before him, he believes that psychedelics ultimately have the “potential to bring about a paradigm shift in psychiatry, neuroscience, and pharmacology.” In the Big Think video above, the professor answers 24 big questions about psychedelics, from “What are the main effects of psychedelics?,” to “How do psychedelics work in the brain?” and “What are the biggest risks of psychedelics?,” to “Will psychedelics answer the hard problem of consciousness?” Johnson covers a lot of ground here. Settle in. The video runs 2+ hours.

Related Content

Michael Pollan, Sam Harris & Others Explain How Psychedelics Can Change Your Mind

Inside MK-Ultra, the CIA’s Secret Program That Used LSD to Achieve Mind Control (1953-1973)

Aldous Huxley, Psychedelics Enthusiast, Lectures About “the Visionary Experience” at MIT (1962)

?si=N6JQU7bXNRhsFgOq

Though it enjoys a particular popularity here in the twenty-first century, the rigorously equanimous Stoic worldview comes to us through the work of three figures from antiquity: Epictetus, Seneca, and Marcus Aurelius. Epictetus was born and raised a slave. Seneca, the son of rhetorician Seneca the Elder, became an advisor to Nero (a position that ultimately forced him to take his own life). Marcus Aurelius, the most exalted of the three, actually did the top job himself, ruling the Roman Empire from 161 to 180 AD. He also left behind a text, the Meditations, that stands alongside Epictetus’ Enchiridion and Seneca’s many essays and letters as a pillar of the canon of Stoicism.

It is from the Meditations that this series of six videos from Youtube channel Einzelgänger draws its wisdom. Each of them introduces different aspects of Marcus Aurelius’ interpretation of Stoicism and applies them to our everyday life here in modernity, presenting strategies for staying calm, not feeling harm, accepting what comes our way, and not being troubled by the actions of others.

Though the importance of these aims can be illustrated any number of ways, their achievement depends on accepting the notion central to all Stoic thought: “the dichotomy of control,” which dictates that “some things are in our control and others aren’t.” When life hurts, “it often means that we care about things we have no control over, and by doing so, we let them control us.”

All the Stoics understood this, but for Marcus Aurelius, “being unperturbed by things outside of his control allowed him to cope with the many responsibilities and challenges he faced as an emperor, and to focus on the task he believed he was given by the gods.” He knew that “it’s not the outside world and the events that take place in it, our bodies included, that hurt us, but our thoughts, memories, and fantasies regarding them.” To indulge those fantasies means to live in perpetual conflict with reality, and thus in perpetual, and futile, grievance against it. The stronger our judgments about what happens, “the more vulnerable we become to the whims of Fortuna, the unpredictable goddess of luck, chance, and fate,” forces that eventually get the better of us all — even if we happen to have the world’s mightiest empire at our command.

Related content:

How to Be a Stoic in Your Everyday Life: Philosophy Professor Massimo Pigliucci Explains

Three Huge Volumes of Stoic Writings by Seneca Now Free Online, Thanks to Tim Ferriss

350 Animated Videos That Will Teach You Philosophy, from Ancient to Post-Modern

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Another chapter from the Annals of Unlikely Performances…

Last week, we highlighted Chuck Berry performing with the Bee Gees on a 1973 episode of the Midnight Special. It’s a pairing that doesn’t work on paper. But, on stage, it’s magic. The same goes for when Berry sang with Tom Jones on a 1974 episode of the same show. It’s magic once again.

If you’re a veteran OC reader, you know that Jones could sing with anyone. On his variety show, This Is Tom Jones, he shared the stage with Janis Joplin, not to mention Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, and Stevie Wonder. It worked. Just watch the expression on Janis and Crosby’s face.

Now 83, Tom Jones and his voice are still going strong. Below, you can watch him sing “Samson And Delilah” in 2021.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content

Janis Joplin & Tom Jones Bring the House Down in an Unlikely Duet of “Raise Your Hand” (1969)

Jimmy Buffett wrote “Margaritaville” in 1977. It ended up being his only song to reach the pop Top 10. But the song carried him for the next 45 years. When you think Margaritaville, you think of an easy-breezy way of life. And that simple idea infused the brand of Buffett’s Margaritaville business empire. Between the song’s birth and the singer’s death this weekend, Buffett created a Margaritaville business empire that included bars, restaurants, casinos, beach resorts, retirement communities, cruises, packaged foods, apparel, footwear, and beyond. This spring, Buffett improbably made Forbes‘ list of billionaires. Above, you can watch a young Jimmy Buffet perform “Margaritaville” in 1978, right at the beginning of the song’s long journey from hit, to brand, to commercial empire.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

“We lunched up-stairs at Botin’s,” writes Ernest Hemingway near the end of The Sun Also Rises (1926). “It is one of the best restaurants in the world. We had roast suckling pig and drank rioja alta.” You can do the very same thing today, a century after the period of that novel — and indeed, you also could’ve done it two centuries before the period of that novel, for Botin’s was established in 1725, and now stands as the oldest restaurant in continuous operation. Founded as Casa Botín by a Frenchman named Jean Botin, it passed in 1753 into the hands of one of his nephews, who re-christened it Sobrino de Botín. Whatever the place has been called over this whole time, its oven has never once gone cold.

?si=-fSM9okYlxvKCpTd

“It is our jewel, our crown jewel,” Botín’s deputy manager Javier Sanchéz Álvarez says of that oven in the Great Big Story video above. “It needs to keep hot at night and be ready to roast in the morning.” What it has to roast is, of course, the restaurant’s signature cochinillo, or suckling pig, about which you can learn more from the Food Insider video just above.

“It’s exactly the same recipe and tradition,” says Sanchéz Álvarez. “Absolutely everything is done in the exact same way as in the old days,” down to the application of the spices, butter, wine, and salt to the raw pork before it enters the historic oven belly-up. “It’s very important that the skin of the cochinillo is very crunchy,” he adds. “If the skin isn’t crunchy, it’s not good.”

Needless to say, Botín is poorly placed to win the favor of the world’s vegetarians. But it does robust business nevertheless, having pulled through the COVID-19 pandemic (with, at the very least, its oven still lit), and more recently received a visit from superstar food vlogger Mark Wiens. Its enduring success surely owes to its more-than-proven ability to deliver on a simple promise: “We will serve you a hearty suckling pick with some good potatoes and a serving of good Spanish ham,” as Sanchéz Álvarez puts it. Working at the restaurant for more than 40 of its 298 years has made it “like home to me,” he says, employing the common Spanish expression of feeling como un pez en el agua — though, given the nature of Botín’s menu, a more terrestrial metaphor is surely in order.

via Mental Floss

Related content:

The Spanish Earth: Ernest Hemingway’s 1937 Film on The Spanish Civil War

Historic Spain in Time Lapse Film

A Visit to the World’s Oldest Hotel, Japan’s Nishiyama Onsen Keiunkan, Established in 705 AD

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Hand binding a book, using primarily 15-century methods and materials sounds like a major undertaking, rife with pitfalls and frustration.

A far more relaxing activity is watching Four Keys Book Arts’ wordless, 24-minute highlights reel of self-taught bookbinder Dennis tackling that same assignment, above. (Bonus – it’s a guaranteed treat for those prone to autonomous sensory meridian response tingles.)

Dennis, whose other recent forays into bespoke bookbinding include a number of elegant matchbox sized volumes and upcycling three Dungeons & Dragons rulebooks into a tome bound in vegetable tanned goatskin, labored on the late-medieval Gothic reproduction for over 60 hours.

For research on this type of binding, he turned to book designer J.A. Szirmai’s The Archaeology of Medieval Bookbinding, and while the goal was never 100% period accuracy, Dennis notes that the craft of traditional hand-binding has remained virtually unchanged for centuries:

The medieval binder would have found many of the tools and techniques to be very familiar. The single biggest anachronism is my use of synthetic PVA glue rather than period-appropriate animal glue. The second historic anomaly is my use of marbled paper, though it could be argued that the earliest European marbled papers of the mid-17th century do overlap with this binding style. The nonpareil pattern I have chosen for the endpapers, though, dates from the 1820’s, and so is distinctly out of place. But apart from those, virtually all of the other materials in this book would have been available to the medieval bookbinder.

Those craving a more step-by-step explanation should set time aside to view the longer videos, below, in which Dennis shares such time-consuming, detail-oriented tasks as trimming and tidying the edges with a cabinet scraper and bookbinder’s plough, sewing endbands to support and protect the book’s head and the spine, and decorating the leather cover with a hand-tooled floral pattern embellished with gold foil highlights.

Rather than cut corners, he literally cuts corners – the metal clasp and corner guards – from a .8mm thick sheet of brass.

Only the final video is narrated, so be sure to activate closed captioning / subtitles in the YouTube toolbar to read his commentary.

Materials and tools used in this project:

Text Paper: Fabriano Accademia 120 gsm drawing paper, 65 x 50 cm, long grain

Endpapers: Four Keys Book Arts handmade marbled paper, Fabriano Accademia 120 gsm drawing paper, red handmade paper

Thread: Undyed Linen 25/3, unknown brand

Cords: Leather, unknown type, roughly 3 oz/ 1 mm

Wax: Natural Beeswax

Glue: Mix of Acid-Free PVA and Methyl Cellulose, 3:2 ratio.

Paper Knife (made from an old kitchen knife)

Bone Folder (handmade in-house)

Scrap book board, various sizes/thickness

Pressing Boards (1/2″ maple plywood, made in house)

Cast-Iron Book Press (Patrick Ritchie, Edinburgh, circa 1850)

Stainless Steel rulers, various sizes

Small Stanley Knife

Maple Laying Press (handmade in-house)

Small Carpenter’s Square, unknown brand

Pencil (Blackwing)

Steel dividers, unknown brand

Lithography Stone (circa 1925)

Cotton Rag

Agate Burnisher

Piercing Cradle (handmade in-house)

Awl

2″ natural bristle brush, generic

parchment release paper

blotting paper

Acetate barrier sheets, .01 gauge

Dahle Vantage 12e Guillotine (found at a thrift store)

Scissors

Bookbinding Needles

Sewing Frame (handmade in-house)

Brass H-Keys (handmade in-house)

Linen sewing tapes, 12 mm

Pins

Watch a full playlist of Four Keys Book Arts’ Medieval Gothic Binding videos here. See more of Dennis book binding projects on Four Keys Book Arts’ Instagram.

Related Content

Wonderfully Weird & Ingenious Medieval Books

When Medieval Manuscripts Were Recycled & Used to Make the First Printed Books

The Medieval Masterpiece, the Book of Kells, Has Been Digitized and Put Online

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Your Pretty Much Pop team Mark Linsenmayer, Lawrence Ware, Sarahlyn Bruck, and Al Baker talk about Charlie Brooker’s British anthology TV series that began in 2011 and recently released its sixth season.

How has this show evolved from satirical science fiction to something more often just horror studies that study human nature? We talk about our favorite episodes and what does and doesn’t work. Does the show have to be so dark to make its point? Does it always have a point, or is some of it just fun?

To refresh yourself or learn more about these individual episode names that we keep dropping, check out the Wikipedia article listing all the episodes. A Guardian article rates how well ten of the episodes predicted the future, and a Vulture article ranks every single episode.

We mention philosopher Charles Mills talking about a Black Mirror episode on another podcast.

Follow us @law_writes, @sarahlynbruck, @ixisnox, @MarkLinsenmayer.

Hear more Pretty Much Pop, including recent episodes on Barbie and Indiana Jones. Support the show and hear bonus talking for this and nearly every other episode at patreon.com/prettymuchpop or by choosing a paid subscription through Apple Podcasts. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network. Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts.

“The inhabitants of fifteenth-century Florence included Brunelleschi, Ghiberti, Donatello, Masaccio, Filippo Lippi, Fra Angelico, Verrocchio, Botticelli, Leonardo, and Michelangelo,” writes tech investor and essayist Paul Graham. “Milan at the time was as big as Florence. How many fifteenth century Milanese artists can you name?” Once you get thinking about the question of “what happened to the Milanese Leonardo,” it’s hard to stop. So it seems to have been for network physicist Albert-László Barabási, whose work on the distribution of scientific genius we featured last month here on Open Culture. Graham’s speculation also applied to that line of inquiry, but it applies much more directly to Barabási’s work on artistic fame.

“In the contemporary art context, the value of an artwork is determined by very complex networks,” Barabási explains in the Big Think video above. Factors include “who is the artist, where has that artist exhibited before, where was that work exhibited before, who owns it and who owned it before, and how these multiple links connect to the canon and to art history in general.” In search of a clearer understanding of their relative importance and the nature of their interactions, he and a team of researchers gathered all the relevant data to produce “a worldwide map of institutions, where it turned out that the most central nodes — the most connected nodes — happened to be also the most prestigious museums: MoMA, Tate, Gagosian Gallery.”

So far, this may come as no great surprise to anyone familiar with the art world. But the most interesting characteristic of this network map, Barabási says, is that it “allowed us to predict artistic success. That is, if you give me an artist and their first five exhibits, I’d put them on the map and we could fast-forward their career to where they’re going to be ten, twenty years from now.” In the past, the artists who made it big tended to start their career in some proximity to the map’s central institutions.”It’s very difficult for somebody to enter from the periphery. But our research shows that it’s possible”: such artists “exhibited everywhere they were willing to show their work,” eventually making influential connections by these “many random acts of exhibition.”

This research, published a few years ago in Science, “confirms how important networks are in art, and how important it is for an artist to really understand the networks in which their work is embedded.” Location matters a great deal, but that doesn’t consign talent to irrelevance. The more talented artists are, “the more and higher-level institutions are willing to work with them.” If you’re an artist, “who was willing to work with you in your first five exhibits is already a measure of your talent and your future journey in the art world.” But even if you’re not an artist, you underestimate simultaneous importance of ability and connections — and how those two factors interact with each other — at your peril. From art to science to insurance claims adjustment to professional bowling, every field involves networks: networks that, as Barabási’s work has shown us, aren’t always visible.

Related Content:

An Interactive Social Network of Abstract Artists: Kandinsky, Picasso, Brancusi & Many More

An Animated Bill Murray on the Advantages & Disadvantages of Fame

Why Einstein Was a “Peerless” Genius, and Hawking Was an “Ordinary” Genius: A Scientist Explains

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Alex Woolner knows how to put a degree in English to good use.

Past projects include a feminist typewriter blog, retrofitting sticker vending machines to dispense poetry, and a free residency program for emerging artists at a multidisciplinary studio she co-founded with playwright and painter Jason Montgomery in Easthampton, Massachusetts.

More recently, the poet and international educator has combined her interest in amigurumi crocheted animals and ChatGPT, the open source AI chatbot.

Having crocheted an amigurumi narwhal for a nephew earlier this year, she hopped on ChatGPT and asked it to create “a crochet pattern for a narwhal stuffed animal using worsted weight yarn.”

The result might have discouraged another querent, but Woolner got out her crochet hook and sallied forth, following ChatGPTs instructions to the letter, despite a number of red flags indicating that the chatbot’s grasp of narwhal anatomy was highly unreliable.

Its ignorance is part of its DNA. As a large language model, ChatGPT is capable of producing predictive text based on vast amounts of data in its memory bank. But it can’t see images.

As Amit Katwala writes in Wired:

It has no idea what a cat looks like or even what crochet is. It simply connects words that frequently appear together in its training data. The result is superficially plausible passages of text that often fall apart when exposed to the scrutiny of an expert—what’s been called “fluent bullshit.”

It’s also not too hot at math, a skill set knitters and crocheters bring to bear reading patterns, which traffic in numbers of rows and stitches, indicated by abbreviations that really flummox a chatbot.

An example of beginner-level instructions from a free downloadable pattern for a cute amigurumi shark:

DORSAL FIN (gray yarn)

Rnd 1: in a mr work 3 sc, 2 hdc, 1 sc (6)

Rnd 2: 3 sc, 1 hdc inc, 1 hdc, 1 sc (7)

Rnd 3: 3 sc, 2 hdc, 1 hdc inc, 1 sc (8)

Rnd 4: 3 sc, 1 hdc inc, 3 hdc, 1 sc inc (10)

Rnd 5: 3 sc, 1 hdc, 1 hdc inc, 3 hdc, 1 sc, 1 sc inc (12)

Rnd 6: 3 sc, 6 hdc, 3 sc (12)

Rnd 7: sc even (12); F/O and leave a long strand of yarn to sew the dorsal fin between rnds # 18-23. Do not stuff the fin.

Pity poor ChatGPT, though, like Woolner, it tried.

Their collaboration became a cause célèbre when Woolner debuted the “AI generated narwhal crochet monstrosity” on TikTok, aptly comparing the large tusk ChatGPT had her position atop its head to a chef’s toque.

Is that the best AI can do?

A recent This American Life episode details how Sebastien Bubeck, a machine learning researcher at Microsoft, commanded another large language model, GPT-4, to create code that TikZ, a vector graphics producer, could use to “draw” a unicorn.

This collaborative experiment was perhaps more empirically successful than the ChatGPT amigurumi patterns Woolner dutifully rendered in yarn and fiberfill. This American Life’s David Kestenbaum was sufficiently awed by the resulting image to hazard a guess that “when people eventually write the history of this crazy moment we are in, they may include this unicorn.”

It’s not good, but it’s a fucking unicorn. The body is just an oval. It’s got four stupid rectangles for legs. But there are little squares for hooves. There’s a mane, an oval for the head. And on top of the head, a tiny yellow triangle, the horn. This is insane to say, but I felt like I was seeing inside its head. Like it had pieced together some idea of what a unicorn looked like and this was it.

Let’s not poo poo the merits of Woolner’s ongoing explorations though. As one commenter observed, it seems she’s “found a way to instantiate the weird messed up artifacts of AI generated images in the physical universe.”

To which Woolner responded that she “will either be spared or be one of the first to perish when AI takes over governance of us meat sacks.”

In the meantime, she’s continuing to harness ChatGPT to birth more monstrous amigurumi. Gerald the Narwhal’s has been joined by a cat, an otter, Norma the Normal Fish, XL the Newt, and Skein Green, a pelican bearing get well wishes for author and science vlogger Hank Green.

When retired mathematician Daina Taimina, author of Crocheting Adventures with Hyperbolic Planes, told the Daily Beast that Gerald would have resembled a narwhal more closely had Woolner supplied ChatGPT with more specifics, Woolner agreed to give it another go.

Two weeks later, the Daily Beast pronounced this attempt, nicknamed Gerard, “even less narwhal-looking than the first. Its body was a massive stuffed triangle, and its tusk looked like a gumdrop at one end.”

Woolner dubbed Gerard possibly the most frustrating AI-generated amigurumi of her acquaintance, owing to an onslaught of specificity on ChatCPT’s part. It overloaded her with instructions for every individual stitch, sometimes calling for more stitches in a row than existed in the entire pattern, then dipped out without telling her how to complete the body and tail.

As silly as it all may seem, Woolner believes her ChatGPT amigurumi collabs are a healthy model for artists using AI technology:

I think if there are ways for people in the arts to continue to create, but also approach AI as a tool and as a potential collaborator, that is really interesting. Because then we can start to branch out into completely different, new art forms and creative expressions—things that we couldn’t necessarily do before or didn’t have the spark or the idea to do can be explored.

If you, like Hank Green, have fallen for one of Woolner’s unholy creations, downloadable patterns are available here for $2 a pop.

Those seeking alternatives to fiberfill are advised to stuff their amigurumi with “abandoned hopes and dreams” or “all those free tee shirts you get from giving blood and running road races or whatever you do for fun”.

Related Content

An Artist Crochets a Life-Size, Anatomically-Correct Skeleton, Complete with Organs

A Biostatistician Uses Crochet to Visualize the Frightening Infection Rates of the Coronavirus

Make an Adorable Crocheted Freddie Mercury; Download a Free Crochet Pattern Online

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

You may not hear the term mash-up very often these days, but the concept itself isn’t exactly the early-two-thousands fad that it might imply. It seems that, as soon as technology made it possible for enthusiasts to combine ostensibly unrelated pieces of media — the more incongruous, the better — they started doing so: take the synchronization of The Wizard of Oz and Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon, known as The Dark Side of the Rainbow. But even back in the seventies, the art of the proto-mash-up wasn’t practiced only by rogue projectionists in altered states of mind, as evidenced by the 1976 20th Century Fox Release All This and World War II, which assembled real and dramatized footage of that epoch-making geopolitical conflict with Beatles covers.

Upon its release, All This and World War II “was received so harshly it was pulled from theaters after two weeks and never spoken of again,” as Keith Phipps writes at The Reveal.

Those who actually seek it out and watch it today will find that it gets off to an even less auspicious start than they might imagine: “A clip of Charlie Chan (Sidney Toler) skeptically receiving the news of Neville Chamberlain’s ‘peace in our time’ declaration in the 1939 film City in Darkness gives way to a cover of ‘Magical Mystery Tour’ by ’70s soft-rock giants Ambrosia. Accompanying the song: footage of swastika banners, German soldiers marching in formation, and a climactic appearance from a smiling Adolf Hitler, by implication the organizer of the ‘mystery tour’ that was World War II.”

The other recording artists of the seventies enlisted to supply new versions of well-known Beatles numbers include the Bee Gees, Elton John, the Who’s Keith Moon, and Peter Gabriel, names that assured the soundtrack album (which you can hear on this Youtube playlist) a much greater success than the film itself, with its fever-dream mixture of newsreels Axis and Allied with 20th Century Fox war-picture clips.

As for what everyone involved was thinking in the first place, Phipps quotes an explanation that soundtrack producer Lou Reizner once provided to UPI: “It would have been easy to take the music of the era and dub it to match the action on screen. But we’d have lost the young audience. We want all age groups to see this picture because we think it makes a statement about the absurdity of war. It is the definitive anti-war film” — or, as Phipps puts it, the definitive “cult film in search of cult.”

via Metafilter

Related content:

Hear 100 Amazing Cover Versions of Beatles Songs

Dark Side of the Rainbow: Pink Floyd Meets The Wizard of Oz in One of the Earliest Mash-Ups

Watch 85,000 Historic Newsreel Films from British Pathé Free Online (1910-2008)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

We have, above, a pair of socks. You can tell that much by looking at them, of course, but what’s less obvious at a glance is their age: this pair dates back to 250-420 AD, and were excavated in Egypt at the end of the nineteenth century. That information comes from the site of the Victoria and Albert Museum, where you can learn more about not just these Egyptian socks but the distinctive, now-vanished technique used to make socks in Egypt at the time: “nålbindning, sometimes called knotless netting or single needle knitting — a technique closer to sewing than knitting,” which, as we know it, wouldn’t emerge until the eleventh century in Islamic Egypt. The technique still remains in use today.

Time consuming and skill-intensive, nålbindning produced especially close-fitting garments, and “fit is of particular importance in a cold climate but also for protecting feet clothed in sandals only.” And yes, it seems that socks like these were indeed worn with sandals, a function indicated by their split-toe construction.

A few years ago, we featured archaeological research here on Open Culture pointing to the ancient Romans as the first sock-and-sandal wearers in human history. These particular socks were also made in the time of the Roman Empire, though they were unearthed at its far reaches, from “the burial grounds of ancient Oxyrhynchus, a Greek colony on the Nile.”

As Smithsonian.com’s Emily Spivack writes, “We don’t know for sure whether these socks were for everyday use, worn with a pair of sandals to do the ancient Egyptian equivalent of running errands or heading to work — or if they were used as ceremonial offerings to the dead (they were found by burial grounds, after all).” But the fact that their appearance is so striking to us today, at least sixteen centuries later, reminds us that we aren’t as familiar as we think with the world that produced them. And if, to our modern eyes, they even look a bit goofy — though less goofy than they would if worn properly, along with a pair of sandals — we should remember the painstaking method with which they must have been crafted, as well as the way they constitute a thread, as it were, through the history of western civilization.

Related content:

An Ancient Egyptian Homework Assignment from 1800 Years Ago: Some Things Are Truly Timeless

3,200-Year-Old Egyptian Tablet Records Excuses for Why People Missed Work: “The Scorpion Bit Him,” “Brewing Beer” & More

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Kids who dig robotics usually start out building projects that mimic insects in both appearance and action.

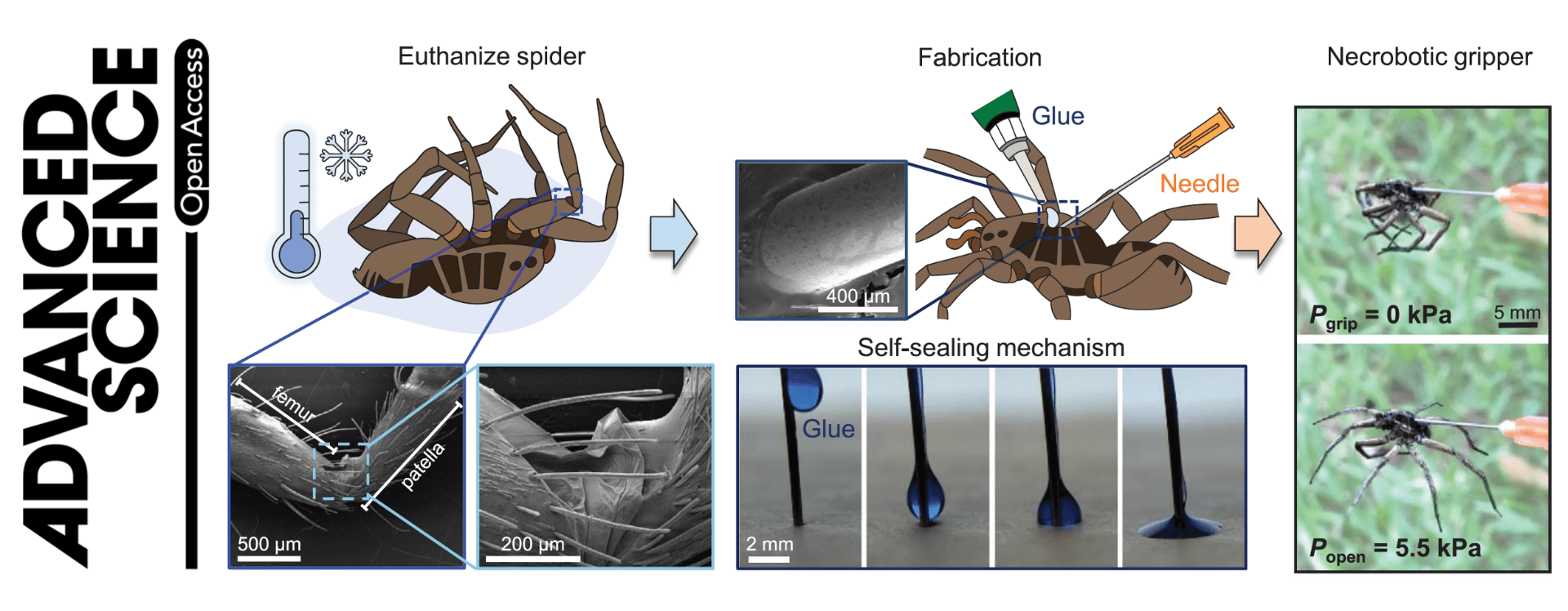

Daniel Preston, Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Rice University and PhD student Faye Yap come at it from a different angle. Rather than designing robots that move like insects, they repurpose dead wolf spiders as robotic claws.

Very little modification is required.

Yap explains that, unlike mammals, spiders lack antagonistic muscles:

They only have flexor muscles, which allow their legs to curl in, and they extend them outward by hydraulic pressure. When they die, they lose the ability to actively pressurize their bodies. That’s why they curl up.

When a scientifically inclined human inserts a needle into a deceased spider’s hydraulic prosoma chamber, seals it with superglue, and delivers a tiny puff of air from a handheld syringe, all eight legs will straighten like fingers on jazz hands.

These necrobiotic spider gripper tools can lift around 130% of their body weight – smaller spiders are capable of handling more – and each one is good for approximately 1000 grips before degrading.

Preston and Yap envision putting the spiders to work sorting or moving small scale objects, assembling microelectronics, or capturing insects in the wild for further study.

Eventually, they hope to be able to isolate the movements of individual legs, as living spiders can.

Environmentally, these necrobiotic parts have a major advantage in that they’re fully biodegradable. When they’re no longer technologically viable, they can be composted. (Humans can be too, for that matter…)

The idea is as innovative as it is offbeat. As a soft robotics specialist, Preston is always seeking alternatives to hard plastics, metals and electronics:

We use all kinds of interesting new materials like hydrogels and elastomers that can be actuated by things like chemical reactions, pneumatics and light. We even have some recent work on textiles and wearables…The spider falls into this line of inquiry. It’s something that hasn’t been used before but has a lot of potential.”

Conquer any lingering arachnophobia by reading Yap and Preston’s research article, Necrobotics: Biotic Materials as Ready-to-Use Actuators, here.

Hat Tip to Open Culture reader Dawn Yow.

Related Content

Isaac Asimov Explains His Three Laws of Robots

200-Year-Old Robots That Play Music, Shoot Arrows & Even Write Poems: Watch Automatons in Action

MIT Creates Amazing Self-Folding Origami Robots & Leaping Cheetah Robots

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

The samurai class first took shape in Japan more than 800 years ago, and it captures the imagination still today. Up until at least the seventeenth century, their life and work seems to have been relatively prestigious and well-compensated. By Katsu Kokichi’s day, however, the way of the samurai wasn’t what it used to be. Born in 1802, Katsu lived through the first half of the century in which the samurai as we know it would go extinct, rendered unsupportable by evolving military technology and a changing social order. But reading his autobiography Musui’s Story: The Autobiography of a Tokugawa Samurai, one gets the feeling that he wouldn’t exactly have excelled even in his profession’s heyday.

“From childhood, Katsu was given to mischief,” says the site of the book’s publisher. “He ran away from home, once at thirteen, making his way as a beggar on the great trunk road between Edo and Kyoto, and again at twenty, posing as the emissary of a feudal lord. He eventually married and had children but never obtained official preferment and was forced to supplement a meager stipend by dealing in swords, selling protection to shopkeepers, and generally using his muscle and wits.”

But don’t take it from The University of Arizona Press when you can hear selections of Katsu’s dissolute picaresque of a life retold in his own words — and narrated in English translation — in the animated Voices of the Past video above.

“Unable to distinguish right and wrong, I took my excesses as the behavior of heroes and brave men,” writes a 42-year-old Katsu in a particularly self-flagellating passage. “In everything, I was misguided, and I will never know how much anguish I caused my relatives, parents, wife, and children. Even more reprehensible, I behaved most disloyally to my lord and master the shogun and with uttermost defiance to my superiors. Thus did I finally bring myself to this low estate.” But if was from that inglorious position that Katsu could produce such an entertaining and illuminating set of reflections. He may have been no Miyamoto Musashi, but he left us a more vivid description of everyday life in nineteenth-century Japan than his exalted contemporaries could have managed.

Related content:

Hand-Colored 1860s Photographs Reveal the Last Days of Samurai Japan

How to Be a Samurai: A 17th Century Code for Life & War

The 17th Century Japanese Samurai Who Sailed to Europe, Met the Pope & Became a Roman Citizen

Hear an Ancient Chinese Historian Describe The Roman Empire (and Other Voices of the Past)

Watch the Oldest Japanese Anime Film, Jun’ichi Kōuchi’s The Dull Sword (1917)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

In 1903, the Romanovs, Russia’s last and longest-reigning royal family, held a lavish costume ball. It was to be their final blowout, and perhaps also the “last great royal ball” in Europe, writes the Vintage News. The party took place at the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, 14 years before Czar Nicholas II’s abdication, on the 290th anniversary of Romanov rule. The Czar invited 390 guests and the ball ranged over two days of festivities, with elaborate 17th-century boyar costumes, including “38 original royal items of the 17th century from the armory in Moscow.”

“The first day featured feasting and dancing,” notes Russia Beyond, “and a masked ball was held on the second. Everything was captured in a photo album that continues to inspire artists to this day.” The entire Romanov family gathered for a photograph on the staircase of the Hermitage theater, the last time they would all be photographed together.

It is like seeing two different dead worlds superimposed on each other—the Romanovs’ playacting their beginning while standing on the threshold of their last days.

With the irony of hindsight, we will always look upon these poised aristocrats as doomed to violent death and exile. In a morbid turn of mind, I can’t help thinking of the baroque gothic of “The Masque of the Red Death,” Edgar Allan Poe’s story about a doomed aristocracy who seal themselves inside a costume ball while a contagion ravages the world outside: “The external world could take care of itself,” Poe’s narrator says. “In the meantime it was folly to grieve or to think. The prince had provided all the appliances of pleasure…. It was a voluptuous scene, that masquerade.”

Maybe in our imagination, the Romanovs and their friends seem haunted by the weight of suffering outside their palace walls, in both their country and around Europe as the old order fell apart. Or perhaps they just look haunted the way everyone does in photographs from over 100 years ago. Does the colorizing of these photos by Russian artist Klimbim—who has done similar work with images of WW2 soldiers and portraits of Russian poets and writers—make them less ghostly?

It puts flesh on the pale monochromatic faces, and gives the lavish costuming and furniture texture and dimension. Some of the images almost look like art nouveau illustrations (and resemble those of some of the finest illustrators of Poe’s work) and the work of contemporary painters like Gustav Klimt. Maybe it’s just me, but it seems that unease lingers in the eyes of some subjects—Empress Alexandra Fedorovna among them—a certain vague and troubled apprehension.

In their book A Lifelong Passion, authors Andrei Maylunas and Sergei Mironenko quote the Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovitch who remembered the event as “the last spectacular ball in the history of the empire.” The Grand Duke also recalled that “a new and hostile Russia glared through the large windows of the palace… while we danced, the workers were striking and the clouds in the Far East were hanging dangerously low.” As Russia Beyond notes, soon after this celebration, “The global economic crisis marked the beginning of the end for the Russian Empire, and the court ceased to hold balls.”

In 1904, the Russo-Japanese War began, a war Russia was to lose the following year. Then the aristocracy’s power was further weakened by the Revolution of 1905, which Lenin would later call the “Great Dress Rehearsal” for the Revolutionary takeover of 1917. While the aristocracy costumed itself in the trappings of past glory, armies amassed to force their reckoning with the 20th century.

Who knows what thoughts went through the mind of the tzar, tzarina, and their heirs during those two days, and the minds of the almost 400 noblemen and women dressed in costumes specially designed by artist Sergey Solomko, who drew from the work of several historians to make accurate 17th-century recreations, while Peter Carl Fabergé chose the jewelry, including, writes the Vintage News, the tzarina’s “pearls topped by a diamond and emerald-studded crown” and an “enormous emerald” on her brocaded dress?

If the Romanovs had any inkling their almost 300-year dynasty was coming to its end and would take all of the Russian aristocracy with it, they were, at least, determined to go out with the highest style; the family with “almost certainly… the most absolutist powers” would spare no expense to live in their past, no matter what the future held for them. See the original, black and white photos, including that last family portrait, at History Daily, and see several more colorized images at the Vintage News.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2019.

Related Content

Watch Scenes from Czarist Moscow Vividly Restored with Artificial Intelligence (May 1896)

Dostoyevsky Got a Reprieve from the Czar’s Firing Squad and Then Saved Charles Bukowski’s Life

Tsarist Russia Comes to Life in Vivid Color Photographs Taken Circa 1905-1915

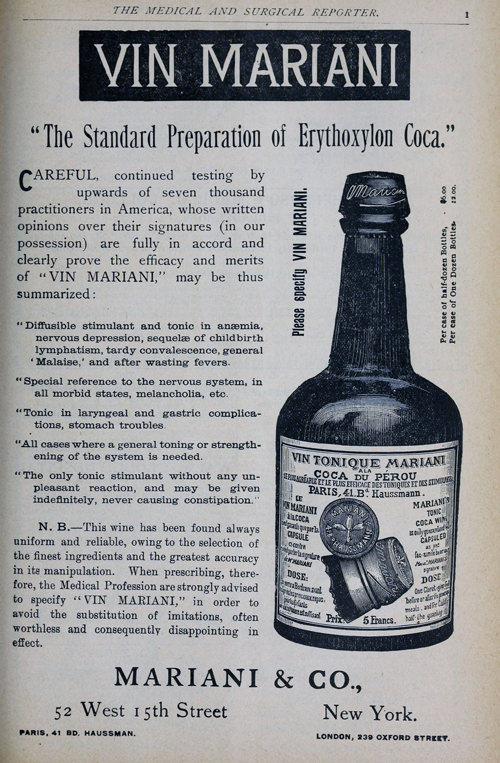

In the neverending quest to elevate themselves above the fray, today’s mixologists – formerly known as bartenders – are putting a modern spin on obscure cocktail recipes, and resurrecting anachronistic spirits like mahia, Chartreuse, Usquebaugh, and absinthe.

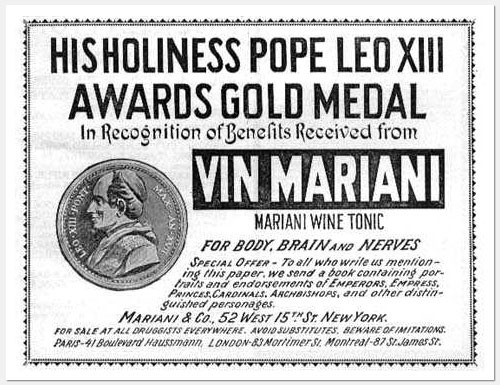

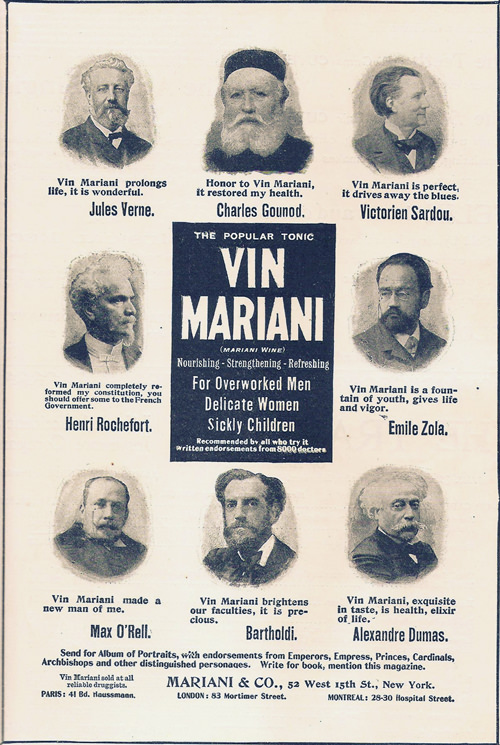

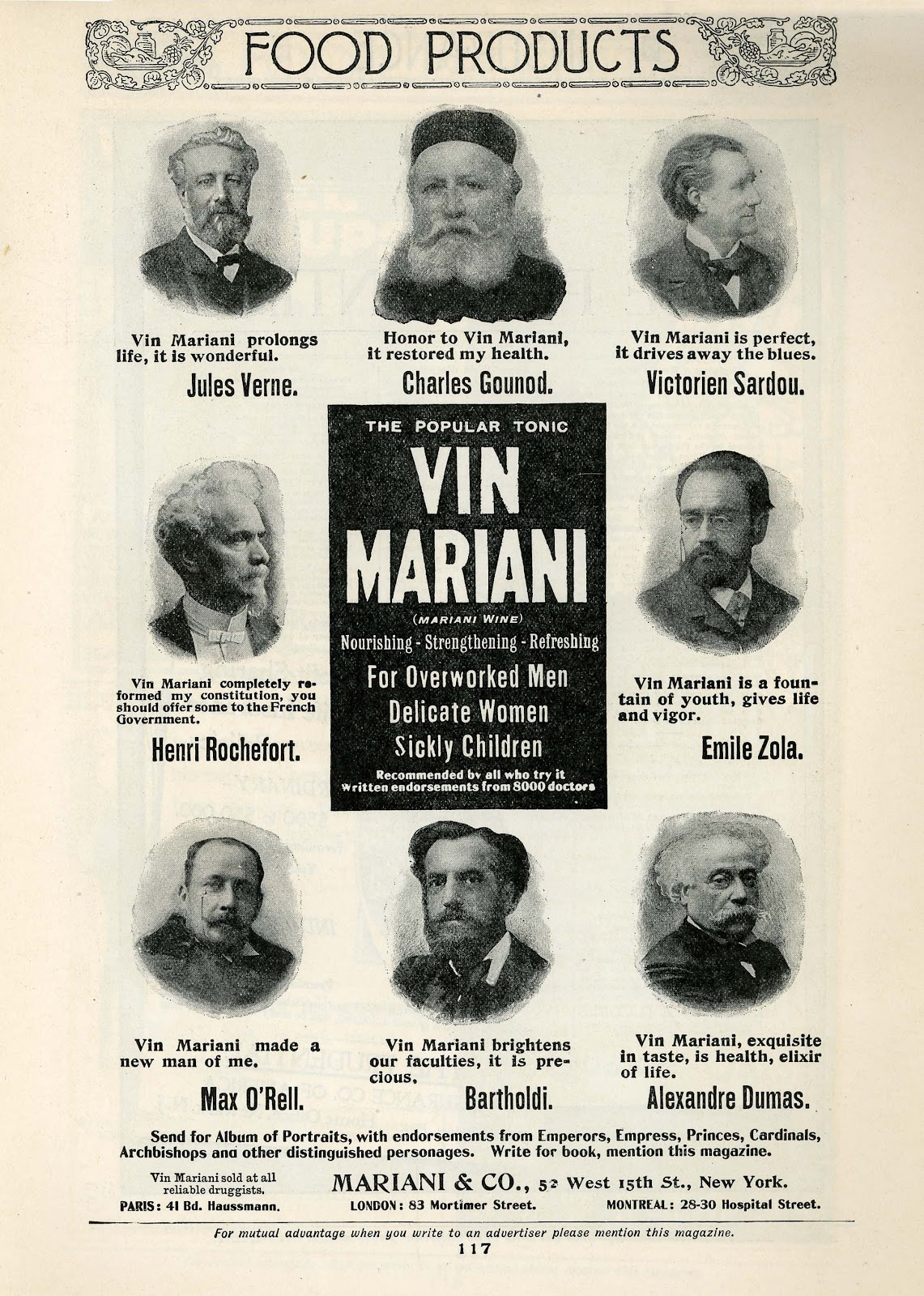

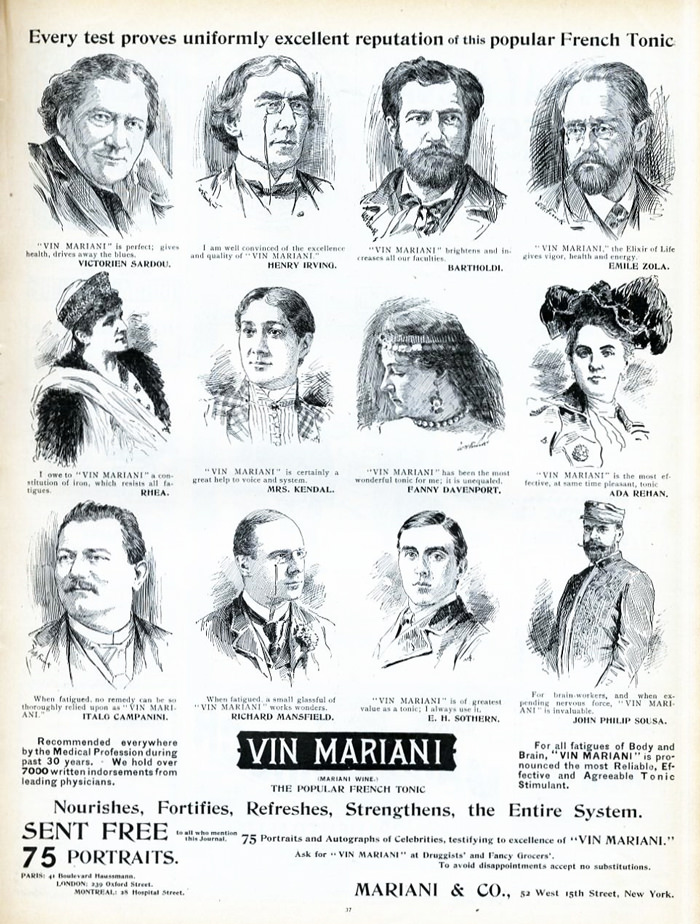

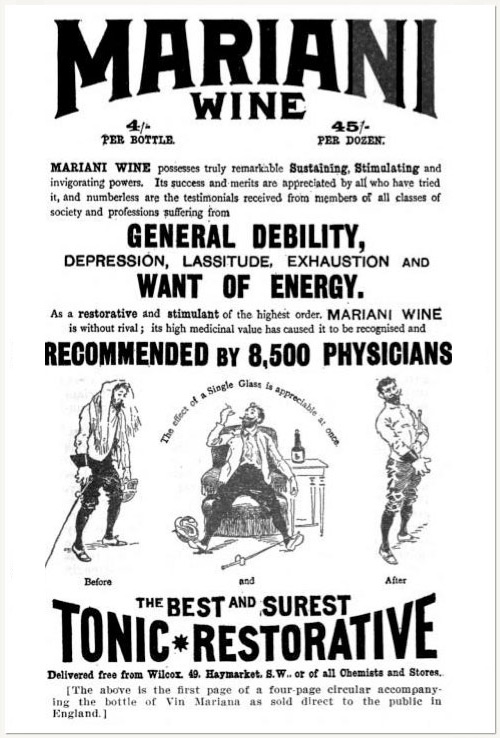

Might we see a return of Vin Mariani, a Belle Époque ‘tonic wine’ that was hit with such august personages as Queen Victoria, Ulysses S. Grant, Alexander Dumas and Emile Zola?

Probably not.

It’s got coca in it, known for its psychoactive alkaloid, cocaine.

Corsican chemist Angelo Mariani came up with the restorative beverage, formally known as Vin Tonique Mariani à la Coca de Peroum, in 1863, inspired by physician and anthropologist Paolo Mantegazza who served as his own guinea pig after observing native use of coca leaves while on a trip to South America:

I sneered at the poor mortals condemned to live in this valley of tears while I, carried on the wings of two leaves of coca, went flying through the spaces of 77,438 words, each more splendid than the one before…An hour later, I was sufficiently calm to write these words in a steady hand: God is unjust because he made man incapable of sustaining the effect of coca all life long. I would rather have a life span of ten years with coca than one of 10,000,000,000,000,000,000 000 centuries without coca.

Mariani identified an untapped opportunity and added ground coca leaves to Bordeaux, at a ratio of 6 milligrams of coca to one ounce of wine.

Unsurprisingly, the resulting concoction not only took the edge off, it was accorded a number of healthful benefits in an age where general cure-alls were highly prized.

The recommended dosage for adults was two or three glasses a day, before or after meals. For kids, the amount could be divided in two.

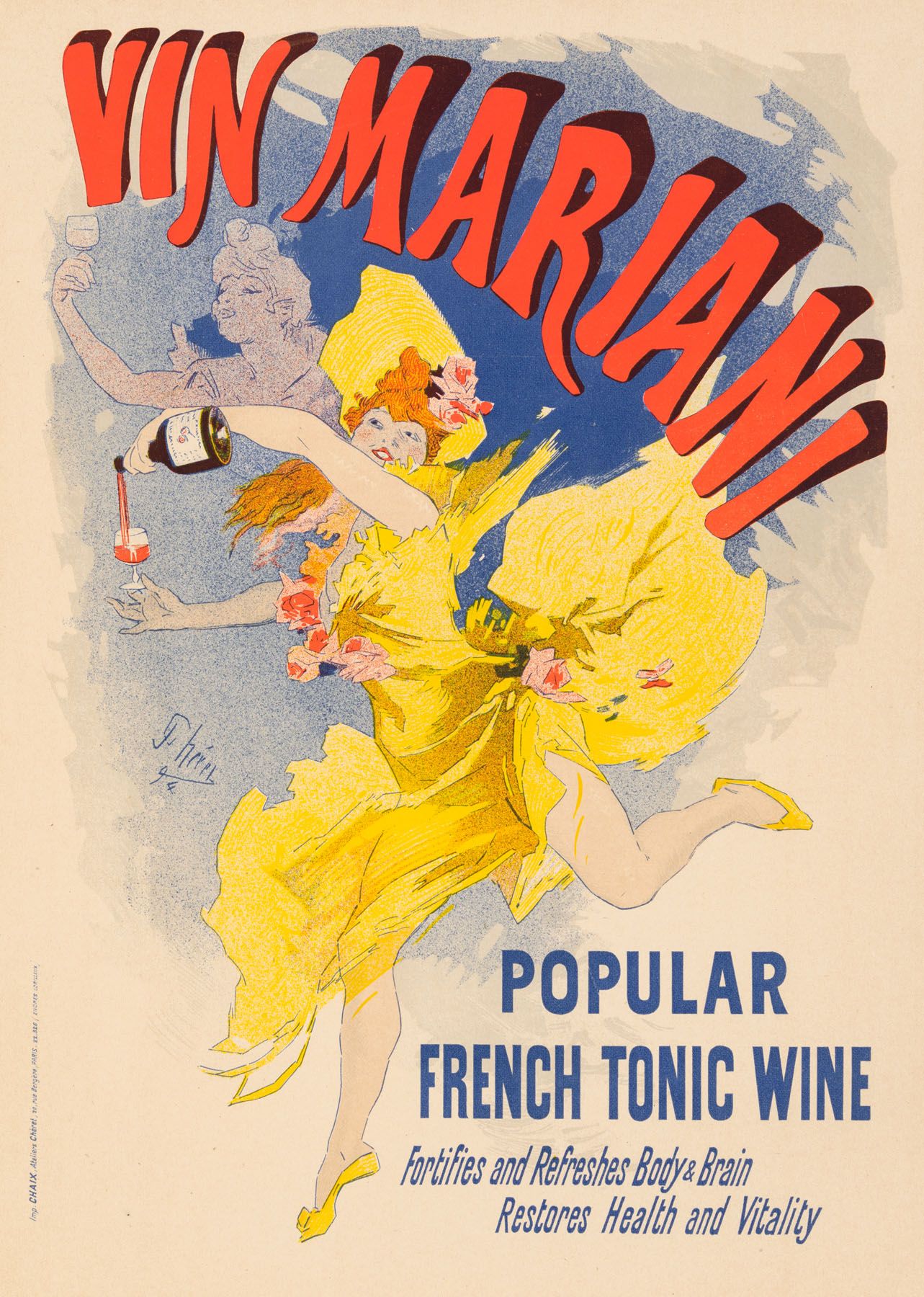

Reigning masters of graphic design were enlisted to promote the miracle elixir.

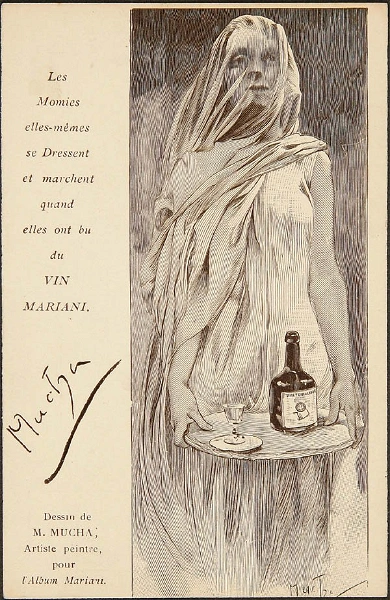

Jules Chéret leaned into its energy boosting effects by depicting a comely young woman clad in skimpy, sheer yellow replenishing her glass mid-leap, while Alphonse Mucha went dark, claiming that “the mummies themselves stand up and walk after drinking Vin Mariani.”

While we’re on the subject of corpse revivers, 21st-century mixologists will please note that a cocktail of Vin Mariani, vermouth and bitters, served with a twist, was a particularly popular preparation, especially across the Atlantic, where Vin Mariani was exported in a more potent version containing 7.2 milligrams of coca.

Angelo Mariani’s innovations were not limited to the chemistry of alcoholic compounds.

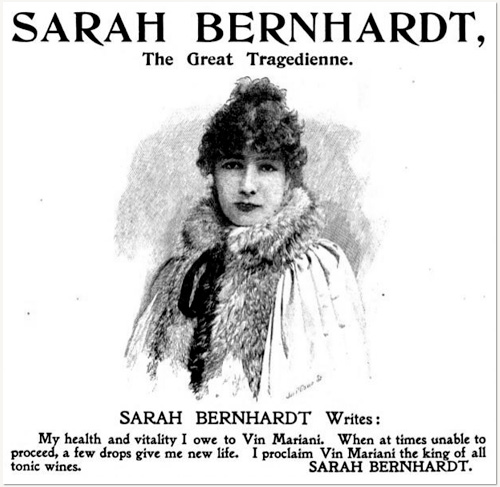

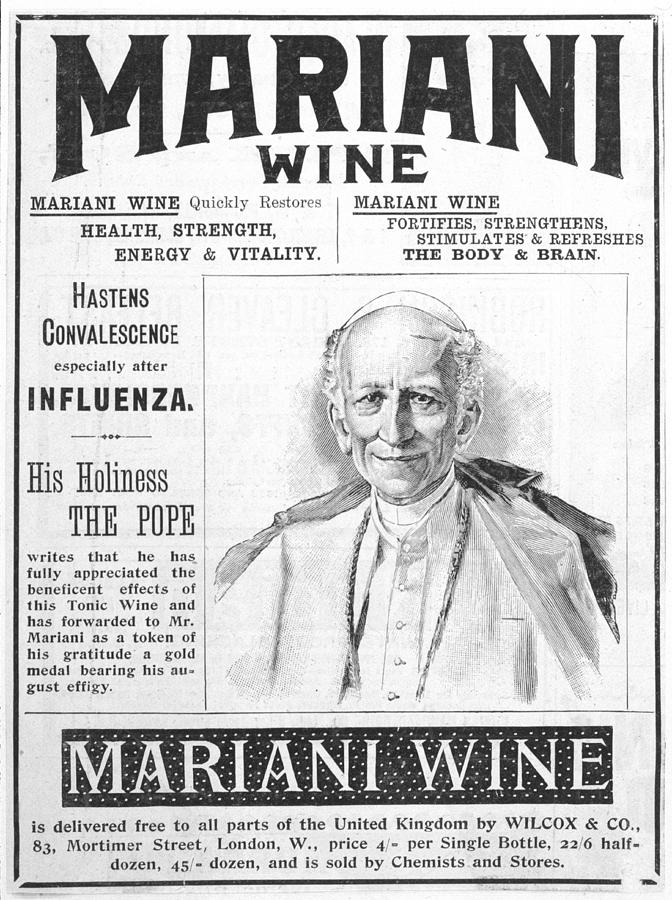

He was also a marketing genius, who curried celebrity favor by sending a complimentary case of Vin Mariani to dozens of famous names, along with a humble request for an endorsement and photo, should the contents prove pleasing.

These accolades were collected and repurposed as advertisements that assured adoring fans and followers of the product’s quality.

Sarah Bernhardt conferred superstar status on the drink, and not so subtly shored up her own, grandly pronouncing the blend the “King of Tonics, Tonic of Kings:”

I have been delighted to find Vin Mariani in all the large cities of the United States, and it has, as always, largely helped to give me that strength so necessary in the performance of the arduous duties which I have imposed upon myself. I never fail to praise its virtues to all my friends and I heartily congratulate upon the success which you so well deserve.

Pope Leo XIII not only carried “a personal hip flask” of the stuff to “fortify himself in those moments when prayer was insufficient,” he invented and awarded a Vatican gold medal to Vin Mariani “in recognition of benefits received.”

Mariani eventually packaged the glowing endorsements he’d been squirreling away as Portraits from Album Mariani. It’s a compendium of famous artists, writers, actors, and musicians of the day, some remembered, mostly not…

Composer John Philip Sousa:

When worn out after a long rehearsal or a performance, I find nothing so helpful as a glass of Vin Mariani. To brain workers and those who expend a great deal of nervous force, it is invaluable.

Opera singer Lillian Blauvelt:

Vin Mariani is the greatest of all tonic stimulants for the voice and system. During my professional career, I have never been without it.

Illustrator Albert Robida:

At last! At last! It has been discovered – they hold it, that celebrated microbe so long sought after – the microbe of microbes that kills all other microbes. It is the great, the wonderful, the incomparable microbe of health! It is, it is Vin Mariani!

(We suspect Robida penned his entry after swallowing more than a few glasses… or he was of a mischievous nature and would’ve fit right in with the Surrealists, the Futurists, Fluxus, or any other movement that jabbed at the bourgeoisie with hyperbole and humor.

Mariani used the album to publish the Philadelphia Medical Times’ defense of celebrity endorsements:

The array of notable names is a strong one. Too strong in standing, as well as in numbers, to allow of the charge of interested motives.

Mariani also included an excerpt from the New York Medical Journal, denouncing the unscrupulous manufacturers of “rival preparations of coca” who pirated Vin Mariani’s glowing reviews, “craftily making those records appear to apply to their own preparations.”

Elsewhere in the album, medical authorities tout Vin Mariani’s success in combatting such maladies as headaches, heart strain, brain exhaustion, spasms, la grippe, laryngeal afflictions, influenza, inordinate irritability and worry.

They fail to mention that it could get you much higher than vins ordinaires, defined, for purposes of this post, as “wines lacking in coca.”

The psychoactive properties of coca definitely received a boost from the alcohol, a collision that gave rise to a third chemical compound, cocaethylene, a long-lasting intoxicant that produces intense euphoria, along with a heightened risk of cardiotoxicity and sudden death.

…some dead celebrities could likely tell us a thing or two about it.

Mariani’s fortunes began to turn early in the 20th century, owing to the Pure Food and Drug Act, the growing temperance movement, and increased public awareness of the dangers of cocaine.

We may never see a Vin Mariani cocktail on the menu at Death & Co, Licorería Limantour, or Paradiso, but the Drug Enforcement Administration’s Museum keeps a bottle on hand.

Related Content

How a Young Sigmund Freud Researched & Got Addicted to Cocaine, the New “Miracle Drug,” in 1894

The Coffee Pot That Fueled Honoré de Balzac’s Coffee Addiction

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

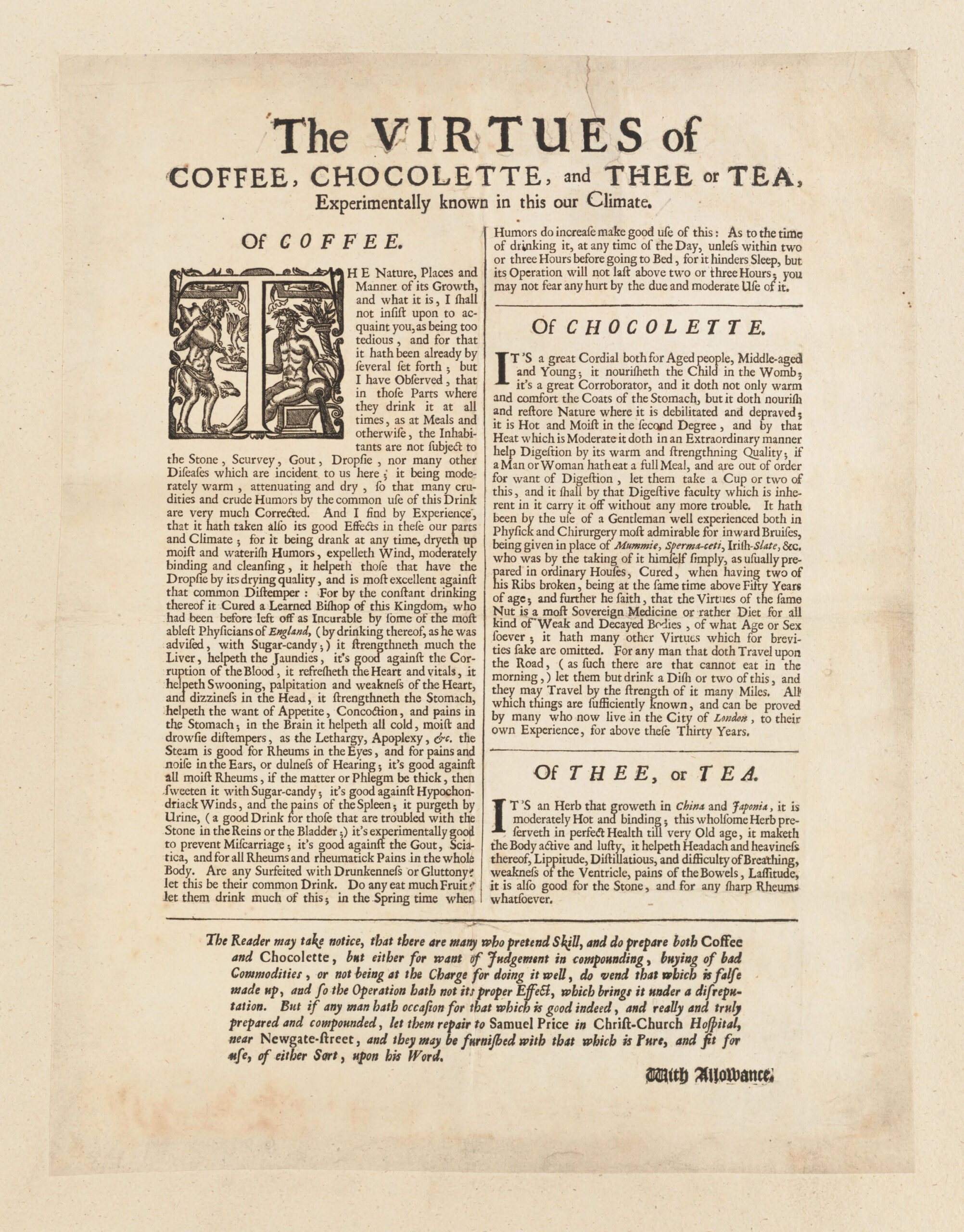

According to many historians, the English Enlightenment may never have happened were it not for coffeehouses, the public sphere where poets, critics, philosophers, legal minds, and other intellectual gadflies regularly met to chatter about the pressing concerns of the day. And yet, writes scholar Bonnie Calhoun, “it was not for the taste of coffee that people flocked to these establishments.”

Indeed, one irate pamphleteer defined coffee, which was at this time without cream or sugar and usually watered down, as “puddle-water, and so ugly in colour and taste [sic].”

No syrupy, high-dollar Macchiatos or smooth, creamy lattes kept them coming back. Rather than the beverage, “it was the nature of the institution that caused its popularity to skyrocket during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.”

How, then, were proprietors to achieve economic growth? Like the owner of the first English coffee-shop did in 1652, London merchant Samuel Price deployed the time-honored tactics of the mountebank, using advertising to make all sorts of claims for coffee’s many “virtues” in order to convince consumers to drink the stuff at home. In the 1690 broadside above, writes Rebecca Onion at Slate, Price made a “litany of claims for coffee’s health benefits,” some of which “we’d recognize today and others that seem far-fetched.” In the latter category are assertions that “coffee-drinking populations didn’t get common diseases” like kidney stones or “Scurvey, Gout, Dropsie.” Coffee could also, Price claimed, improve hearing and “swooning” and was “experimentally good to prevent Miscarriage.”

Among these spurious medical benefits is listed a genuine effect of coffee—its relief of “lethargy.” Price’s other beverages—“Chocolette, and Thee or Tea”—receive much less emphasis since they didn’t require a hard sell. No one needs to be convinced of the benefits of coffee these days—indeed many of us can’t function without it. But as we sit in corporate chain cafes, glued to smartphones and laptop screens and mostly ignoring each other, our coffeehouses have become somewhat pale imitations of those vibrant Enlightenment-era establishments where, writes Calhoun, “men [though rarely women] were encouraged to engage in both verbal and written discourse with regard for wit over rank.”

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2014.

Related Content:

The Birth of Espresso: The Story Behind the Coffee Shots That Fuel Modern Life

Honoré de Balzac Writes About “The Pleasures and Pains of Coffee,” and His Epic Coffee Addiction

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

Salvador Dalí led a long and eventful life, so much so that certain of its chapters outlandish enough to define anyone else’s existence have by now been almost forgotten. “You’ve done some very mysterious things,” Dick Cavett says to Dalí on the 1971 broadcast of his show above. “I don’t know if you like to be asked what they mean, but there was an incident once where you appeared for a lecture in Paris, at the Sorbonne, and you arrived in a Rolls-Royce filled with cauliflowers.” At that, the artist wastes no time launching into an elaborate, semi-intelligible explanation involving rhinoceros horns and the golden ratio.

The incident in question had occurred sixteen years earlier, in 1955. “With bedlam in his mind and a quaint profusion of fresh cauliflower in his Rolls-Royce limousine, Spanish-born Surrealist Painter Salvador Dalí arrived at Paris’ Sorbonne University to unburden himself of some gibberish,” says the contemporary notice in Time. “His subject: ‘Phenomenological Aspects of the Critical Paranoiac Method.’ Some 2,000 ecstatic listeners were soon sharing Salvador’s Dalirium.”

To them he announced his discovery that “‘everything departs from the rhinoceros horn! Everything departs from [Dutch Master] Jan Vermeer’s The Lacemaker! Everything ends up in the cauliflower!’ The rub, apologized Dali, is that cauliflowers are too small to prove this theory conclusively.”

Nearly seven decades later, Honi Soit‘s Nicholas Osiowy takes these ideas rather more seriously than did the sneering correspondent from Time. “Beneath the simple shock value and easy surrealism, it becomes clear Dalí was onto something; the humble cauliflower is considered one of the best examples of the legendary golden ratio,” Osiowy writes. “Cauliflowers, rhinoceroses and anteaters’ tongues were to Dali essential manifestations of a glorious shape; deserving of an explicit depiction in his The Sacrament of the Last Supper,” painted in the year of his Sorbonne lecture. “Shape, the idea of geometry itself, is the unsung magic of not just art but our entire cultural consciousness.” Not that Dalí himself would have copped to communicating that: “I am against any kind of message,” he insists in response to a question from fellow Dick Cavett Show guest, who happened to be silent-film icon Lillian Gish. The seventies didn’t need the surreal; they were the surreal.

Related content:

When Salvador Dali Met Sigmund Freud, and Changed Freud’s Mind About Surrealism (1938)

Salvador Dalí Reveals the Secrets of His Trademark Moustache (1954)

Q: Salvador Dalí, Are You a Crackpot? A: No, I’m Just Almost Crazy (1969)

How Dick Cavett Brought Sophistication to Late Night Talk Shows: Watch 270 Classic Interviews Online

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

The Internet Movie Database credits Shakespeare as the writer on 1787 films, 42 of which have yet to be released.

The Shakespeare Network has compiled a chronological playlist of trailers for 45 of them.

First up is 1935’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, featuring Olivia de Havilland, Jimmy Cagney, Dick Powell, and, in the role of Puck, a 15-year-old Mickey Rooney, hailed by the New York Times as “one of the major delights” of the film, and Variety as “so intent on being cute that he becomes almost annoying.”

Tragedies dominate, with no fewer than six Hamlets, Shakespeare’s most filmed work, and “one of the most fascinating and most thankless tasks in show business” according to novelist and frequent film critic James Agee:

There can never be a definitive production of a play about which no two people in the world can agree. There can never be a thoroughly satisfying production of a play about which so many people feel so personally and so passionately. Very likely there will never be a production good enough to provoke less argument than praise.

Lawrence Olivier, Nicol Williamson, Mel Gibson, Kenneth Branagh, Ethan Hawke, David Tennant – take your pick:

MacBeth, Richard III, Romeo and Juliet, and The Tempest – a comedy – are other crowd-pleasing workhorses, chewy assignments for actors and directors alike.

Those with a taste for deeper cuts will appreciate the inclusion of Ralph Fiennes’ Coriolanus (2011), Branagh’s Love’s Labour’s Lost (2000) and Titus, Julie Taymor’s 1999 adaptation of Shakespeare’s most shocking bloodbath.

Moviegoing connoisseurs of the Bard may feel moved to stump for films that didn’t make the playlist. If you can find a trailer for it, go for it! Lobby the Shakespeare Network on its behalf, or make your case in the comments.

We’ll throw our weight behind Michael Almereyda’s Cymbeline, featuring Ed Harris roaring down the porch steps of a dilapidated Brooklyn Victorian on a motorcycle, the bizarre Romeo.Juliet pairing A-list British vocal talent with an all-feline line-up of Capulets and Montagues, and Shakespeare Behind Bars, a 2005 documentary following twenty incarcerated men who spent nine months delving into The Tempest prior to a production for guards, fellow inmates, and invited guests.

Enjoy the complete playlist of Shakespeare film trailers below. They move from 1935 to 2021.

Related Content

Take a Virtual Tour of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in London

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

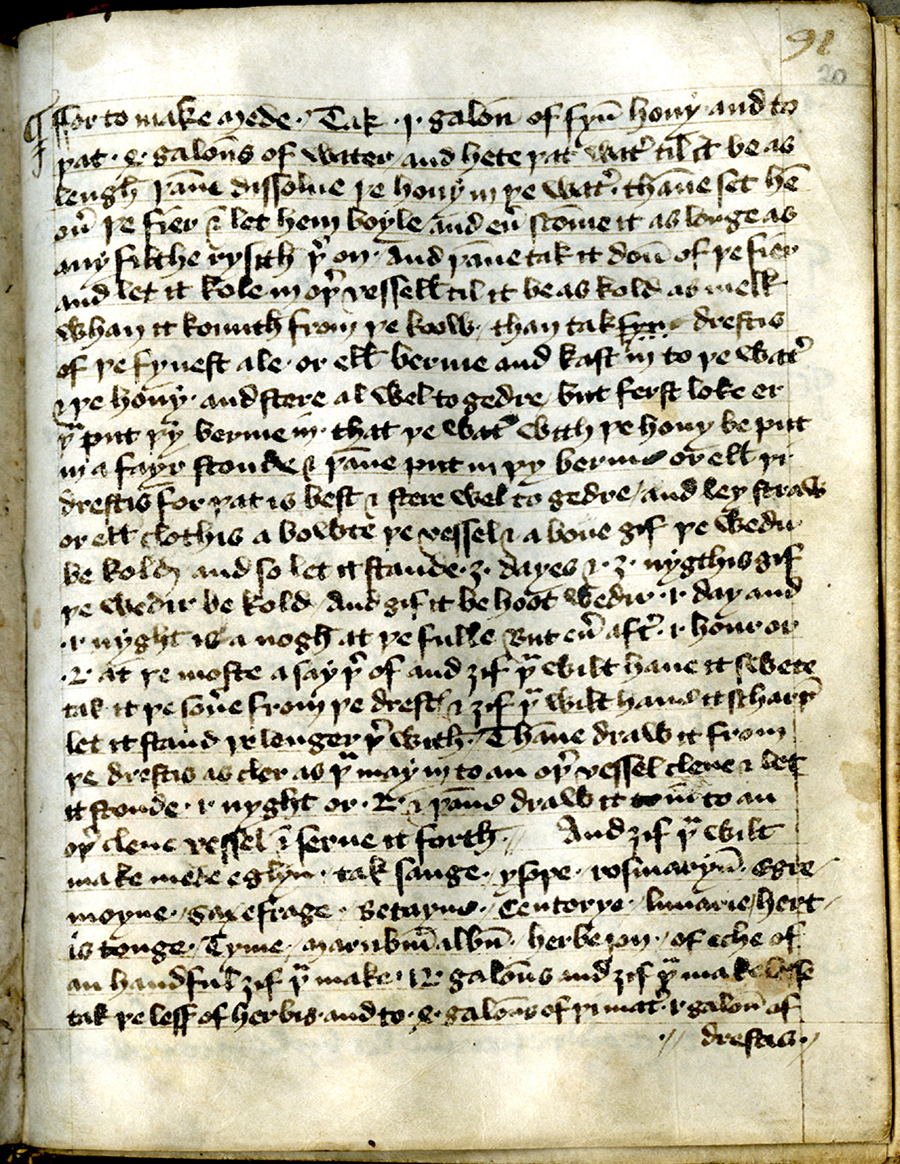

Read a story set in the Middle Ages, Beowulf or anything more recently written, and you’re likely to run across a reference to mead, which seems often to have been imbibed heartily in halls dedicated to that very activity. The same goes for medieval-themed plays, movies, and even video games. Take Assassin’s Creed Valhalla, described by Max Miller, host of Youtube channel Tasting History, as “a history-based game of, like, my favorite time period — Saxons and Vikings, you know, fightin’ it out — so I’m assuming that there’s going to be mead in there somewhere.” He uploaded the video, below, in the fall of 2020, just before that game’s release, but according to the Assassin’s Creed Wiki, he was right: there is, indeed, mead in there.

Perhaps throwing back a digital horn of mead in a video game has its satisfactions, but surely it would only make us curious to taste the real thing. Hence Miller’s episode project of “making medieval mead like a viking,” which requires only three basic ingredients: water, honey, and ale dregs or dry ale yeast. (The set of required tools is a bit more complex, involving several different vessels and, ideally, a “bubbler” to let out the carbonation.)