Context may not count for everything in art. But as underscored by everyone from Marcel Duchamp (or Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven) to the journalists who occasionally convince virtuoso musicians to busk in dingy public spaces, it certainly counts for something. Whether or not you believe that works of art retain the same essential value no matter where they’re beheld, some environments are surely more conducive to appreciation than others. The question of just which design elements make the difference has occupied museum architects for centuries, and in New York City alone, you can directly experience more than 200 years of bold exercises and experiments in the form.

In the Architectural Digest video above, architect Michael Wyetzner (previously featured here on Open Culture for his exegeses of New York’s apartments, bridges, and subway stations, as well as Central Park and the Chrysler Building) uses his expert knowledge to reveal the design choices that have gone into the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, and the Frick Collection. No two of these famous art institutions were conceived in quite the same period, none look or feel quite the same as the others, and we can be reasonably sure that no single piece of art would look quite the same if it were moved between any of them.

Occupying five blocks of Central Park, MoMA is less a building than a collection of buildings — each added at a different time, in a style of that time — and indeed, less a collection of buildings than “a city unto itself,” as Wyetzner puts it. (No wonder Claudia and Jamie Kincaid could run away from home and go unnoticed living in it.) The comparatively modest MoMA has also grown addition-by-addition, beginning with a “stripped-down form of modernism” that stood well out on the West 53rd street of the late thirties. It opened as the first of the many “clean white boxes” that would appear across the country — and later the world — to show the art of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

The original MoMA building remains striking today, but it’s now flanked by expansions from the hands of Philip Johnson, Cesar Pelli, Yoshio Taniguchi, and Jean Nouvel. Much less likely to have anything attached to it is the Guggenheim, with its instantly recognizable spiral design by Frank Lloyd Wright. Based on an idea by Le Corbusier, its narrow atrium-wrapping galleries do present certain difficulties for the proper display of large-scale artworks. Wyetzner also mentions the oft-heard criticism of Wright’s having “created a monument to himself — but it’s one hell of a monument.”

Last comes “the original building for the Whitney Museum of American Art, which later became the Met Breuer, which now has become the Frick. Who knows what it’ll become next.” The second of its names refers to its architect, the Bauhaus-trained Marcel Breuer (he of the Wassily chair), whose muscular design “slices off” the museum from the brownstone neighborhood that surrounds it. With its “open, loft-like spaces,” it provides a context meant for the art of its time, much as the Met, MoMA, and the Guggenheim do for the art of theirs. But all these institutions have succeeded just as much by carving out contexts of their own in the open-air museum of architecture and urbanism that is New York City.

Related content:

Architect Breaks Down Five of the Most Iconic New York City Apartments

The 5 Innovative Bridges That Make New York City, New York City

An Architect Breaks Down the Design of New York City Subway Stations, from the Oldest to Newest

A Whirlwind Architectural Tour of the New York Public Library — “Hidden Details” and All

A 3D Animation Shows the Evolution of New York City (1524 — 2023)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Nearly two and a half centuries after its founding, the United States of America is still both celebrated and derided as a young country. Examined on the whole, the US may or may not seem less mature than other lands in any obvious way, but the difference manifests much more clearly on the level of cities. For even among those founded before the independence of the country itself, no American city has yet attained 500 official years of age. But in the case of New York City, we can trace its formation through half a millennium of history, as rendered in the 3D animated video from InfoGeek above.

The long version of New York’s story begins in 1524, the year Giovanni da Verrazzano commanded the French ship La Dauphine into what we now know as New York Harbor. While he and his crew did not, of course, get the dramatic forest-of-skyscrapers view for which that approach would later be celebrated, they would, perhaps, have seen an actual forest, as well as other elements of a natural landscape that would have appeared sublimely untouched. A century later, the Dutch there founded the trading outpost of New Amsterdam, which commenced the written history of New York — as well as the aggressive development that would eventually come to characterize the city and its culture.

New Amsterdam became New York in 1664, one of the many historical events that scroll past in the window at the video’s lower-left corner. At that point in time, the population had grown to about 3,600, a figure counted at the bottom of the frame. Yet even as we see streets roll out, buildings rise, and trees sprout rapidly around us over the next 150 or so years of our stroll, and even after New York becomes America’s largest city in 1790, we must bear in mind that its century hasn’t even begun. It’s something of an irony that the hugely destructive Great Fire of 1835 precedes a developmental push that makes the city, even to our twenty-first-century eyes, look almost modern.

Later in the nineteenth century, we witness the appearance of Central Park and the introduction of motorcars; by the turn of the twentieth, New York’s population approaches three and a half million. Walking down Wall Street (and into the Great Depression), we pass just-materializing landmarks that remain iconic today, like the Chrysler Building, the Empire State Building and — after a somewhat dramatic fast-forward in time — Frank Lloyd Wright’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Minoru Yamasaki’s ill-fated World Trade Center. We’re now well into the New York of living memory, and even when the animation has passed the creative decrepitude of the seventies and eighties and arrives at the city as it was last year (population: 7,888,120), we sense that its evolution has only just begun.

Related content:

New York City: A Social History (A Free Online Course from N.Y.U.)

Immaculately Restored Film Lets You Revisit Life in New York City in 1911

Scenes of New York City in 1945 Colorized & Revived with Artificial Intelligence

The Lost Neighborhood Buried Under New York City’s Central Park

An Architect Demystifies the Art Deco Design of the Iconic Chrysler Building (1930)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

“Modern architecture died in St Louis, Missouri on July 15, 1972, at 3:32pm (or thereabouts).” This oft-quoted pronouncement by cultural and architectural theorist Charles Jencks refers to the demolition of the Wendell O. Pruitt Homes and William Igoe Apartments. The fate of that short-lived public housing complex, better and more infamously known as Pruitt-Igoe, still holds rhetorical value in America in arguments against the supposed social-engineering ambitions made concrete (often literally) in large-scale postwar modernist buildings. Though the true story is more complicated, the fact remains that, whenever we pinpoint it, modern architecture was widely regarded as “dead.” What would come after it?

Why, postmodernism, of course. Jencks did more than his part to define modernism’s anything-goes successor movement with The Language of Post-Modern Architecture, in which he tells the tale of Pruitt-Igoe, which was then relatively recent history.

The first edition came out in 1977, early days indeed in the life of postmodernism, which in a video from Historic England architectural historian Elain Harwood calls “the style of the nineteen-eighties.” Its riots of deliberately incongruous shape and color, as well as its heaped-up unsubtle cultural and historical references, suited that unbridled decade as perfectly as did the elegantly garish furniture of the Memphis group.

In recent years, however, the buildings left behind by postmodernism have got more than a few of us asking questions — questions like, “Are they intentionally weird and tacky, or just designed with no taste?” That’s how Youtuber Betty Chen puts it in the ARTiculations video just above, before launching into an investigation of postmodern architecture’s origin, purpose, and place in the built environment today. In her telling, the style was born in the early nineteen-sixties, when architect Robert Venturi designed a rule-breaking house for his mother in Philadelphia, deciding “to distort the pure order of the modernist box by reintroducing disproportional arrangements of classical elements such as four-pane windows, arches, the pediment, and the decorative dado.”

An important theorist of postmodernism as well as a practitioner (usually working in both roles with his wife and collaborator Denise Scott Brown), Venturi converted arch-modernist Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s declaration that “less is more” into what would become, in effect, postmodernism’s brief manifesto: “Less is a bore.” Venturi described himself as choosing “messy vitality over obvious unity,” and the same could be said of a range of his colleagues in the eighties and nineties: Frank Gehry, Michael Graves, and Charles Moore in America; Also Rossi, Ricardo Bofill, and Bernard Tschumi in Europe; Minoru Takeyama, Kengo Kuma, and Arata Isozaki in Japan.

Postmodern architecture flowered especially in Britain: “The irreverence came from America, the classicism from Europe,” says Harwood. “What British architects did was weave those two elements together.” As one of those architects, Sir Terry Farrell, tells Historic England, “the preceding era had been earnest and anonymous”; after international modernism, the time had come to re-introduce personality, and in a flamboyant manner. His colleague Piers Gough remembers feeling, in the mid-sixties, a certain envy for pop art — “they were doing color, they were doing popular imagery, they had prettier girlfriends” — that inspired them to “ransack popular imagery in architecture.” This project posed certain practical difficulties of its own: “You can design a building to look like a soup can, but the problem really comes when you put the windows in it.”

Renovations to many an aging postmodern building have proven difficult to justify, given that “irreverence and exaggeration are out,” as Brock Keeling writes in a recent Bloomberg piece. “Significant postmodern buildings like the Abrams House in Pittsburgh and the Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego have already been demolished,” and others are endangered: “Fans of the James R. Thompson Center — Helmut Jahn’s 1985 civic building, noted for its sliced-off dome facade and 17-story atrium with blue-and-salmon trim — fear it will deboned in preparation for Google’s new Chicago headquarters.” The true architectural postmodernism enthusiast also appreciates much humbler works, such as Jeffrey Daniels’ Los Angeles Kentucky Fried Chicken franchise that unintentionally evokes of both a chicken and a chicken bucket. Long may it stand.

Related content:

Why Do People Hate Modern Architecture?: A Video Essay

Meet the Memphis Group, the Bob Dylan-Inspired Designers of David Bowie’s Favorite Furniture

Why People Hate Brutalist Buildings on American College Campuses

How the Radical Buildings of the Bauhaus Revolutionized Architecture: A Short Introduction

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

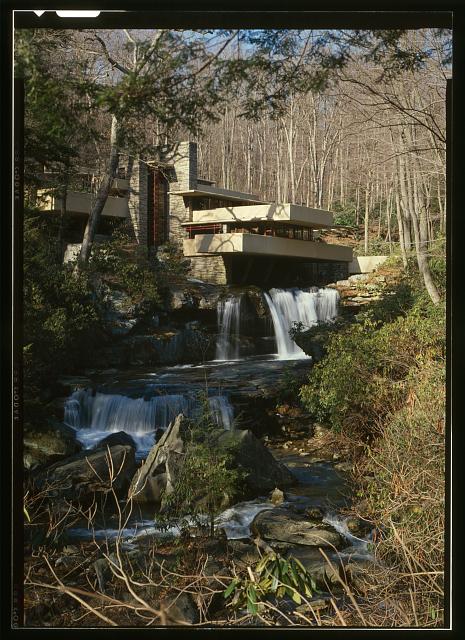

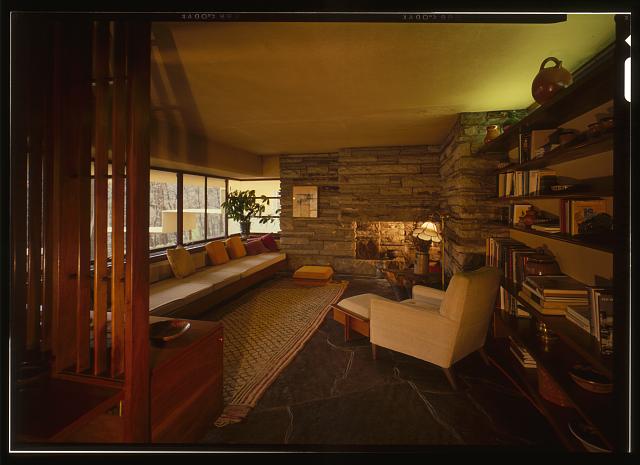

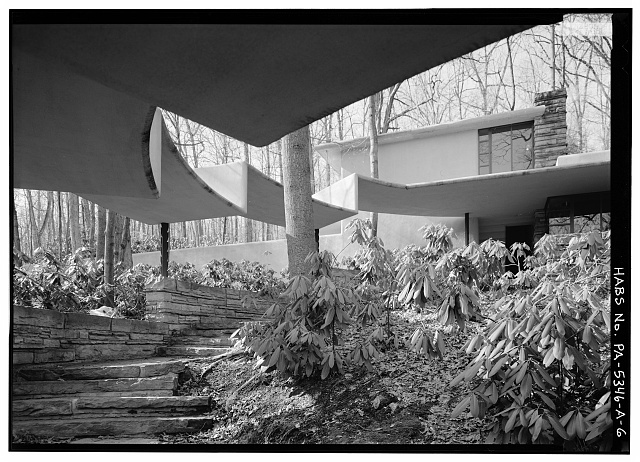

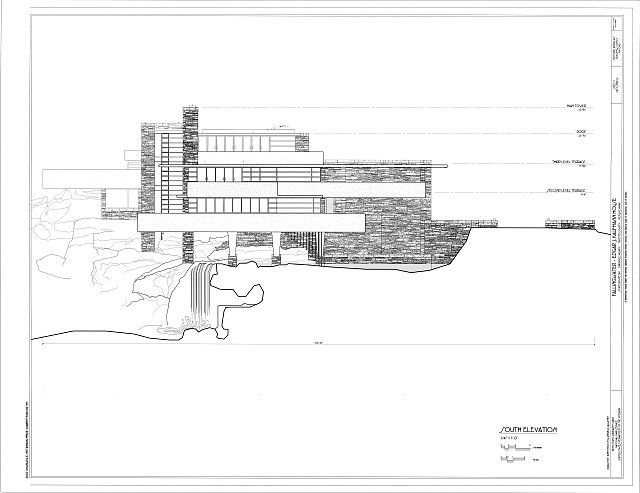

We’ve featured a variety of buildings designed by Frank Lloyd Wright here on Open Culture, from his personal home and studio Taliesin and the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, to a gas station and a doghouse. But if any single structure explains his enduring reputation as a genius of American architecture, and perhaps the genius of American architecture, it must be the house called Fallingwater.

Designed in 1935 for Pittsburgh department-store magnate Edgar J. Kaufmann and his wife Liliane, it sits atop an active waterfall — not below it as Kaufmann had originally requested, to name just one of the disagreements that arose between client and architect throughout the process.

In the event, Wright had his way as far as the positioning of the house on the site, as with much else about the project — and so much the better for its stature in the history of architecture, which has only risen since completion 85 years ago.

Inspired by the Kaufmann’s love of the outdoors, as well as his own appreciation for Japanese architecture, Wright employed techniques to integrate Fallingwater’s spaces with one another, as well as with the surrounding nature. Time magazine wasted no time, as it were, declaring the result Wright’s “most beautiful job”; more recently, it’s received high praise from no less a master Japanese architect than Tadao Ando.

When he visited Fallingwater, Ando experienced first-hand a use of space similar to that which he knew from the built environment of his homeland, and also how the house lets in the sounds of nature. Though such a pilgrimage can greatly expand one’s appreciation of the house, rare is the viewer who fails to be enraptured by pictures alone.

Nearly as astute in the realm of publicity as in that of architecture, Wright would have known that Fallingwater had to photograph well, a quality vividly on display in this archive of 137 high-resolution images at the Library of Congress. From it, you can download color and black-and-white photos of the house’s exterior and interior as well as its plans, which — so the story goes — Wright originally drew up in just two hours after months of inaction. Fallingwater thus stands as not just concrete proof of once-brazen architectural notions, but also vindication for procrastinators everywhere.

Related content:

An Animated Tour of Fallingwater, One of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Finest Creations

What It’s Like to Work in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Iconic Office Building

What Frank Lloyd Wright’s Unusual Windows Tell Us About His Architectural Genius

The Unrealized Projects of Frank Lloyd Wright Get Brought to Life with 3D Digital Reconstructions

1,300 Photos of Famous Modern American Homes Now Online, Courtesy of USC

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

“If you’re in Venice, you might not enjoy it so much if you follow a tour-guide route that gets you to the main attractions.” So says Youtuber Manuel Bravo — whom we’ve previously featured here on Open Culture for his videos on Pompeii, the Duomo di Firenze, and the Great Pyramids of Giza — in “Venice Explained” just above. “But if you get off that road, the charm of Venice is that it’s such a tangled mess that nobody ventures out there” — out, that is, into the “wonderful little neighborhoods with little squares with cisterns and little cafés.” Diminutive though that may sound, Venice comes off in Bravo’s analysis as an entire, unique urban realm unto itself.

“Historically, Venice is really detached from Italy proper,” Bravo says. “It was not a Roman town. It does not have the detritus of Roman ruins scattered around. It does not have remnants of a Roman town plan with cardo and decumanus. It does not even have, well, land.”

Indeed, Venice is famous for having been built in the Adriatic Sea, on a “new fortified ground plane” made of strong trees imported from Croatia. As its political and economic importance grew, so did its “incomparable medieval urban landscape that has remained practically unchanged.” This built environment is full of architectural styles and details seen nowhere else, to which Bravo draws our attention through the course of the video.

Though he recommends departing from the tourist-beaten paths, he doesn’t ignore such world-famous Venetian structures as the Ca d’Oro, “perhaps the most beautiful building in Venice”; the Doge’s Palace with its “antigravity” architecture; and — in detail — the Basilica and Piazza San Marco, “one of the most memorable spatial complexes in the history of urban planning.” No first visit would be complete without some time spent at each of these sites. But “Venice is a city of light,” and in order properly to enjoy it, we must “see it at different times of the day and experience all the nuances that it offers”: good advice in this “most visually seductive of all the cities in the world,” but also worth bearing in mind as a means of appreciating even the less majestic places in which most of us usually find ourselves.

Related content:

How Venice Works: 124 Islands, 183 Canals & 438 Bridges

Take a Virtual Tour of Venice (Its Streets, Plazas & Canals) with Google Street View

Take a High Def, Guided Tour of Pompeii

How the World’s Biggest Dome Was Built: The Story of Filippo Brunelleschi and the Duomo in Florence

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Today it would be viewed as cultural appropriation writ large, but when Louis XIV ordered the construction of a 5-building pleasure pavilion inspired by the Porcelain Tower of Nanjing (a 7th Wonder of the World few French citizens had viewed in person) as an escape from Versailles, and an exotic love nest in which to romp with the Marquise de Montespan, he ignited a craze that spread throughout the West.

Chinoiserie was an aristocratic European fantasy of luxurious Eastern design, what Dung Ngo, founder of AUGUST: A Journal of Travel + Design, describes as “a Western thing that has nothing to do with actual Asian culture:”

Chinoiserie is a little bit like chop suey. It was wholesale invented in the West, based on certain perceptions of Asian culture at the time. It’s very watered down.

And also way over the top, to judge by the rapturous descriptions of the interiors and gardens of Louis XIV’s Trianon de Porcelaine, which stood for less than 20 years.

Image by Hervé Gregoire, via Wikimedia Commons

The blue-and-white Delft tiles meant to mimic Chinese porcelain swiftly fell into disrepair and Madame de Montespan’s successor, her children’s former governess, the Marquise de Maintenon, urged Louis to tear the place down because it was “too cold.”

Her lover did as requested, but elsewhere, the West’s imagination had been captured in a big way.

The burgeoning tea trade between China and the West provided access to Chinese porcelain, textiles, furnishings, and lacquerware, inspiring Western imitations that blur the boundaries between Chinoiserie and Rococo styles

This blend is in evidence in Frederick the Great’s Chinese House in the gardens of Sanssouci (below).

Image by Johann H. Addicks, via Wikimedia Commons

Dr Samuel Wittwer, Director of Palaces and Collections at the Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation, describes how the gilded figure atop the roof “is a mixture of the Greek God Hermes and the Chinese philosopher Confucius:”

His European face is more than just a symbol of intellectual union between Asia and Europe…The figure on the roof has an umbrella, an Asian symbol of social dignity, which he holds in an eastern direction. So the famous ex oriente lux, the good and wise Confucian light from the far east, is blocked by the umbrella. Further down, we notice that the foundations of the building seem to be made of feathers and the Chinese heads over the windows, resting on cushions like trophies, turn into a monkey band in the interior. The frescoes in the cupola mainly depict monkeys and parrots. As we know, these particular animals are great imitators without understanding.

Frederick’s enthusiasm for chinoiserie led him to engage architect Carl von Gontard to follow up the Chinese House with a pagoda-shaped structure he named the Dragon House (below) after the sixteen creatures adorning its roof.

Image by Rigorius, via Wikimedia Commons

Dragons also decorate the roof of the Great Pagoda in London’s Kew Gardens, though the gilded wooden originals either succumbed to the elements or were sold off to settle George IV’s gambling debts in the late 18th century.

Image by MX Granger, via Wikimedia Commons

There are even more dragons to be found on the Chinese Pavilion at Drottningholm, Sweden, an architectural confection constructed by King Adolf Fredrik as a birthday surprise for his queen, Louisa. The queen was met by the entire court, cosplaying in Chinese (or more likely, Chinese-inspired) garments.

Not to be outdone, Russia’s Catherine the Great resolved to “capture by caprice” by building a Chinese Village outside of St. Petersburg.

Image by Макс Вальтер, via Wikimedia Commons

Architect Charles Cameron drew up plans for a series of pavilions surrounding a never-realized octagonal-domed observatory. Instead, eight fewer pavilions than Cameron originally envisioned surround a pagoda based on one in Kew Gardens.

Having survived the Nazi occupation and the Soviet era, the Chinese Village is once again a fantasy plaything for the wealthy. A St. Petersburg real estate developer modernized one of the pavilions to serve as a two-bedroom “weekend cottage.”

Given that no record of the original interiors exists, designer Kirill Istomin wasn’t hamstrung by a mandate to stick close to history, but he and his client still went with “numerous chinoiserie touches” as per a feature in Elle Decor:

Panels of antique wallpapers were framed in gilded bamboo for the master bedroom, and vintage Chinese lanterns, purchased in Paris, hang in the dining and living rooms. The star pieces, however, are a set of 18th-century porcelain teapots, which came from the estate of the late New York socialite and philanthropist Brooke Astor.

Explore cultural critic Aileen Kwun and the Asian American Pacific Islander Design Alliance’s perspective on the still popular design trend of chinoiserie here.

h/t Allie C!

Related Content

How the Ornate Tapestries from the Age of Louis XIV Were Made (and Are Still Made Today)

Free: Download 70,000+ High-Resolution Images of Chinese Art from Taipei’s National Palace Museum

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

If asked to name the best-known tower in London, one could, perhaps, make a fair case for the likes of the Shard or the Gherkin. But whatever their current prominence on the skyline, those works of twenty-first-century starchitecture have yet to develop much value as symbols of the city. If sheer age were the deciding factor, then the Tower of London, the oldest intact building in the capital, would take the top spot, but for how many people outside England does its name call a clear image to mind? No, to find London’s most beloved vertical icon, we must look to the Victorian era, the only historical period that could have given rise to Big Ben.

We must first clarify that Big Ben is not a tower. The building you’re thinking of has been called the Elizabeth Tower since Queen Elizabeth II’s Diamond Jubilee in 2012, but before that its name was the Clock Tower. That was apt enough, since tower’s defining feature has always been the clock at the top — or rather, the four clocks at the top, one for each face.

You can see how they work in the animated video from Youtuber Jared Owen above, which provides a detailed visual and verbal explanation of both the structure’s context and its content, including a tour of the mechanisms that have kept it running nearly without interruption for more than a century and a half.

Only by looking into the tower’s belfry can you see Big Ben, which, as Owens says, is actually the name of the largest of its bells. Its announcement of each hour on the hour — as well as the ringing of the other, smaller bells — is activated by a system of gear trains ultimately driven by gravity, harnessed by the swinging of a large pendulum (to which occasional speed adjustments have always been made with the reliable method of placing pennies on top of it). Owens doesn’t clarify whether or not this is the same pendulum Roger Miller sang about back in the sixties, but at least now we know that, technically speaking, we should interpret the following lyrics as not “the tower, Big Ben” but “the tower; Big Ben.”

Related content:

The Growth of London, from the Romans to the 21st Century, Visualized in a Time-Lapse Animated Map

The Oldest Known Footage of London (1890-1920) Features the City’s Great Landmarks

Prague Monument Doubles as Artist’s Canvas

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

In the small town of Cloquet, Minnesota stands a piece of urban utopia. It takes the surprising form of a gas station, albeit one designed by no less a visionary of American architecture than Frank Lloyd Wright. He originally conceived it as an element of Broadacre City, a form of mechanized rural settlement intended as a Jeffersonian democracy-inspired rebuke against what Wright saw as the evils of the overgrown twentieth century city, first publicly presented in his 1932 book The Disappearing City. “That’s an aspirational title,” says architectural historian Richard Kronick in the Twin Cities PBS video above. “He thought that cities should go away.”

Cities didn’t go away, and Broadacre City remained speculative, though Wright did pursue every opportunity he could identify to bring it closer to reality. “In 1952, Ray and Emma Lindholm commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to build them a home on the south side of Cloquet,” writes photographer Susan Tregoning.

When Wright “discovered that Mr. Lindholm was in the petroleum business, he mentioned that he was quite interested in gas station design.” When Lindholm decided to rebuild a Phillips 66 station a few years later, he accepted Wright’s design proposal, calling it “an experiment to see if a little beauty couldn’t be incorporated in something as commonplace as a service station” — though Wright himself, characteristically, wasn’t thinking in quite such humble terms.

Wright’s R. W. Lindholm Service Station incorporates a cantilevered upper-level “customer lounge,” and the idea, as Kronick puts it, “was that customers would sit up here and while their time away waiting for their cars to be repaired,” and no doubt “discuss the issues of the day.” In Wright’s mind, “this little room is where the details of democracy would be worked out.” As with Southdale Center, Victor Gruen’s pioneering shopping mall that had opened two years earlier in Minneapolis, two hours south of Cloquet, the community aspect of the design never came to fruition: though its windows offer a distinctively American (or to use Wright’s language, Usonian) vista, the customer lounge has a bare, disused look in the pictures visitors take today.

Image by Library of Congress, via Wikimedia Commons

There are many such visitors, who arrive from not just all around the country but all around the world. But when it was last sold in 2018, the buyer it found was relatively local: Minnesota-born Andrew Volna, owner of such Minneapolis operations as vinyl-record manufacturer Noiseland Industries and the once-abandoned, now-renovated Hollywood Theater. “Wright saw the station as a cultural center, somewhere to meet a friend, get your car fixed, and have a cup of coffee while you waited,” writes Tregoning, though he never did make it back out to the finished building before he died in 1959. These sixty-odd years later, perhaps Volna will be the one to turn this unlikely architectural hot spot into an even less likely social one as well.

Related content:

Frank Lloyd Wright Designs an Urban Utopia: See His Hand-Drawn Sketches of Broadacre City (1932)

How Frank Lloyd Wright’s Son Invented Lincoln Logs, “America’s National Toy” (1916)

The Modernist Gas Stations of Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe

When Frank Lloyd Wright Designed a Doghouse, His Smallest Architectural Creation (1956)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

The Brooklyn Bridge ignites the passions of tourists and locals alike.

For every 10,000 visitors who pause in its bike lanes to snap selfies, there’s an alum of nearby PS 261 who celebrated its birthday with a song that mentions the fates of its engineers John and Washington Roebling to the tune of I’ve Been Working on the Railroad.

(A sample chorus: Caisson’s disease! Caissons disease! Caisson’s disease is really bad!)

Native son Adam Suerte of Brooklyn Tattoo estimates that he inks its likeness on a half dozen customers per month. (A temporary option is available for those with commitment issues…)

In 1886, a hustler named Steve Brodie claimed to have survived a jump off of it, a tale propagated by Bugs Bunny.

We watch movies at its feet and draw attention to causes by marching across it.

It continues to mesmerize artists, poets, filmmakers and photographers.

But, as architect Michael Wyetzner makes clear in his most recent video for Architectural Digest, it’s not the only bridge in New York City.

Also, despite what you may have heard, it’s not for sale.

Understandably, the hybrid cable-stayed/suspension superstar connecting Brooklyn to lower Manhattan takes the lead in Wyetzner’s coverage of five bridges that have had an enormous impact on the development of a city whose five boroughs were once traversable solely by ferry.

The other notable players:

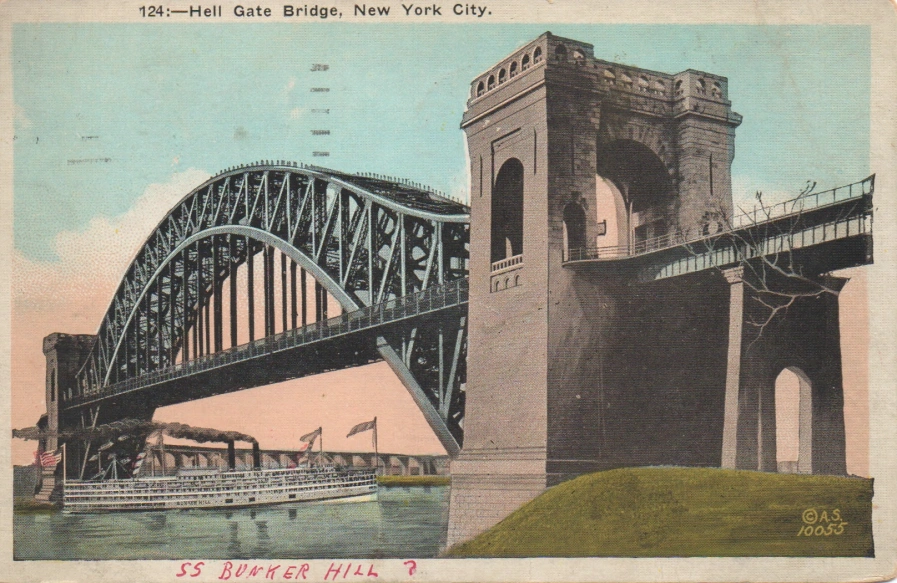

The Hell Gate Bridge – a feat of WWI-era railroad engineering connecting Queens to Randall’s and Wards Island over a particularly perilous stretch of waterway, it was once the longest steel arch bridge in the world.

In his 1921 book New York: The Great Metropolis, painter Peter Marcus noted that “if laid over Manhattan it would reach from Wanamaker’s store at Eighth Street, to One Hundred and Twenty-fifth Street.”

Macomb’s Dam Bridge, a low lying swing bridge whose center portion pivots to accommodate boat traffic on the Harlem River. When construction began in late 1890, the New York Times gushed that it would be a “street built in mid-air” between the Bronx and Washington Heights in upper Manhattan:

It is hardly enough to say of it that it will be the greatest piece of engineering of the kind in the world. Nothing like it has ever been attempted.

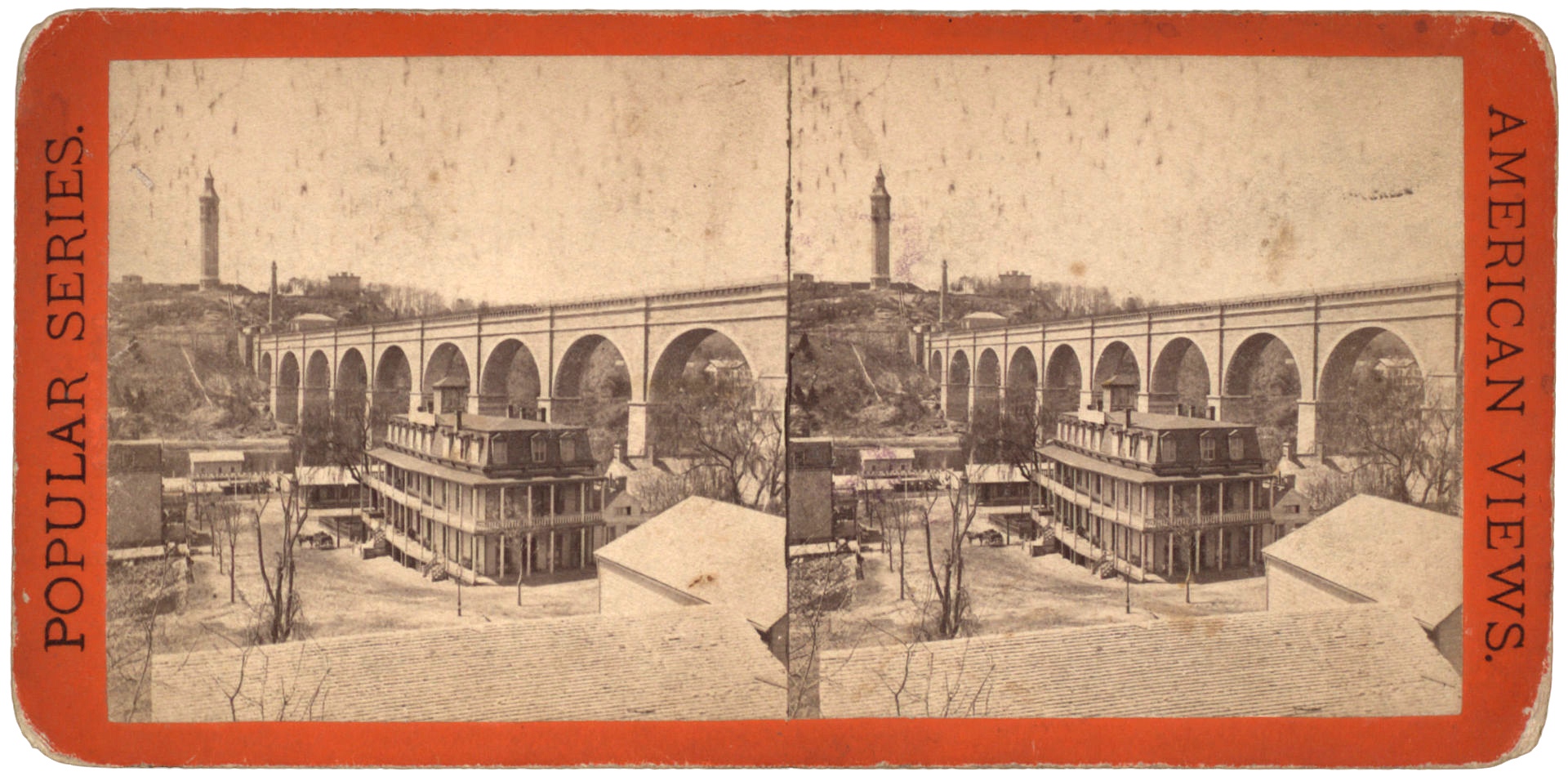

The High Bridge – Originally part of the Croton Aqueduct, it is technically the oldest surviving bridge in the city, as well as a community-led preservation campaign success story. Having languished in the latter part of the 20th century, it is now a beautiful pedestrian bridge whose killer views can be enjoyed without the hassle of Brooklyn Bridge-sized crowds.

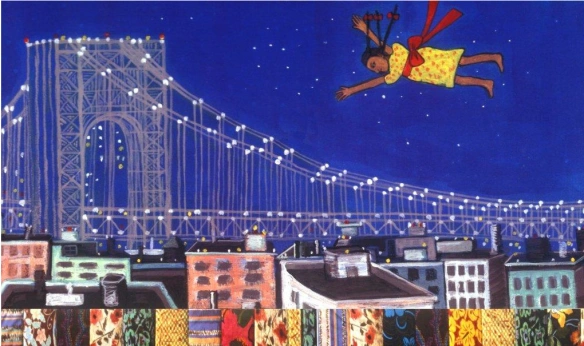

The George Washington Bridge – a major money maker for the Port Authority, it’s not only the world’s busiest bridge, it puts a lot of the bridge in “bridge and tunnel crowd” by connecting Manhattan to New Jersey.

Architecture buffs can geek out on the Concrete Industry Board Award-winning bus station and storied Little Red Lighthouse in its shadow.

The GWB’s most ardent fan has got to be artist Faith Ringgold, who immortalized it in her Tar Beach story quilt and related children’s book:

I never want to be more than three minutes from the George. I could always see it as I grew up. That bridge has been in my life for as long as I can remember. As a kid, I could walk across it anytime I wanted. I love to see it sparkling at night. I moved to New Jersey, and I’m still next to it.

Wyetzner, whose architectural round up shoehorns in a lot of interesting information about public health, economics, transportation, labor practice and New York City history, is actively courting viewers to suggest bridges for a sequel.

We’ll throw our weight behind the Manhattan, the Williamsburg, the Queensboro, the Verrazzano, and the admittedly dark horse 103rd Street Footbridge.

You?

Related Content

How the Brooklyn Bridge Was Built: The Story of One of the Greatest Engineering Feats in History

A Mesmerizing Trip Across the Brooklyn Bridge: Watch Footage from 1899

See New York City in the 1930s and Now: A Side-by-Side Comparison of the Same Streets & Landmarks

An Online Gallery of Over 900,000 Wonderful Photos of Historic New York City

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.