When surveyed, eighty to ninety percent of Americans consider themselves possessed of above-average driving skills. Most of them are, of course, wrong by statistical definition, but the result itself reveals something important about human nature. So does another, lesser-known study that had two groups, one composed of professional comedians and the other composed of average Cornell undergraduates, rank the funniness of a set of jokes. It also asked those students to rank their own ability to identify funny jokes. Naturally, the majority of them credited themselves with an above-average sense of humor.

Not only that, explains the host of the After Skool video above, “those who did the worst placed themselves in the 58th percentile on average. They believed that they were better than 57 other people out of 100. Their real score? Twelfth percentile.” Here we have an example of the cognitive bias whereby “people with a little bit of knowledge or skill in an area believe that they are better than they are,” now commonly known as the Dunning-Kruger effect. It’s named for social psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger, who conducted the aforementioned joke-ranking study as well as others in various domains that all support the same basic finding: the incompetent don’t know how incompetent they are.

“When you’re incompetent, the skills you need to produce a right answer are exactly the skills you need to recognize what a right answer is,” Dunning told Errol Morris in a 2010 interview (the first of a five-part series on anosognosia, or the inability to recognize one’s own lack of ability). “In logical reasoning, in parenting, in management, problem solving, the skills you use to produce the right answer are exactly the same skills you use to evaluate the answer.” What’s more, “even if you are just the most honest, impartial person that you could be, you would still have a problem — namely, when your knowledge or expertise is imperfect, you really don’t know it. Left to your own devices, you just don’t know it. We’re not very good at knowing what we don’t know.”

This brings to mind Donald Rumsfeld’s much-mocked remark about “unknown unknowns,” which Dunning actually considered “the smartest and most modest thing I’ve heard in a year.” (Morris, for his part, would go on to make a documentary about Rumsfeld titled The Unknown Known.) But whether you’re the Secretary of Defense, a celebrated filmmaker, a Youtuber, an essayist, or anything else, you’ve almost certainly been afflicted with the Dunning-Kruger effect. But if we can make a habit of subjecting ourselves to bracing objective assessment, we can — at least, at certain times and certain domains — break free of what T. S. Eliot called the endless struggle to think well of ourselves.

Related content:

Bertrand Russell: The Everyday Benefit of Philosophy Is That It Helps You Live with Uncertainty

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

As Lisa Simpson once memorably remarked, “I can see the music.”

Pretty much anyone can these days.

Just switch on your device’s audio visualizer.

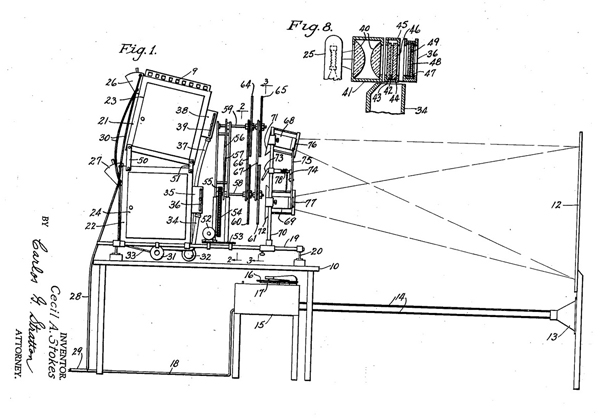

That wasn’t the case in the 1940s, when psychologist Cecil A. Stokes used chemistry and polarized light to invent soothing abstract music videos, a sort of cinematic synesthesia experiment such as can be seen above, in his only known surviving Auroratone.

(The name was suggested by Stokes’ acquaintance, geologist, Arctic explorer and Catholic priest, Bernard R. Hubbard, who found the result reminiscent of the Aurora Borealis.)

The trippy visuals may strike you as a bit of an odd fit with Bing Crosby‘s cover of the sentimental crowdpleaser “Oh Promise Me,” but traumatized WWII vets felt differently.

Army psychologists Herbert E. Rubin and Elias Katz’s research showed that Auroratone films had a therapeutic effect on their patients, including deep relaxation and emotional release.

The music surely contributed to this positive outcome. Other Auroratone films featured “Moonlight Sonata,” “Clair de Lune,” and an organ solo of “I Dream of Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair.”

Drs. Rubin and Katz reported that patients reliably wept during Auroratones set to “The Lost Chord,” “Ave Maria,” and “Home on the Range” – another Crosby number.

In fact, Crosby, always a champion of technology, contributed recordings for a full third of the fifteen known Auroratones free of charge and footed the bill for overseas shipping so the films could be shown to soldiers on active duty and medical leave.

Technophile Crosby was well positioned to understand Stokes’ patented process and apparatus for producing musical rhythm in color – aka Auroratones – but those of us with a shakier grasp of STEM will appreciate light artist John Sonderegger’s explanation of the process, as quoted in filmmaker and media conservator Walter Forsberg’s history of Auroratones for INCITE Journal of Experimental Media:

[Stokes’] procedure was to cut a tape recorded melody into short segments and splice the resulting pieces into tape loops. The audio signal from the first loop was sent to a radio transmitter. The radio waves from the radio transmitter were confined to a tube and focused up through a glass slide on which he had placed a chemical mixture. The radio waves would interact with the solution and trigger the formation of the crystals. In this way each slide would develop a shape interpretive of the loop of music it had been exposed to. Each loop, in sequence, would be converted to a slide. Eventually a set of slides would be completed that was the natural interpretation of the complete musical melody.

Vets suffering from PTSD were not the only ones to embrace these unlikely experimental films.

Patients diagnosed with other mental disorders, youthful offenders, individuals plagued by chronic migraines, and developmentally delayed elementary schoolers also benefited from Auroratones’ soothing effects.

The general public got a taste of the films in department store screenings hyped as “the nearest thing to the Aurora Borealis ever shown”, where the soporific effect of the color patterns were touted as having been created “by MOTHER NATURE HERSELF.”

Auroratones were also shown in church by canny Christian leaders eager to deploy any bells and whistles that might hold a modern flock’s attention.

The Guggenheim Museum‘s brass was vastly less impressed by the Auroratone Foundation of America’s attempts to enlist their support for this “new technique using non-objective art and musical compositions as a means of stimulating the human emotions in a manner so as to be of value to neuro-psychiatrists and psychologists, as well as to teachers and students of both objective and non-objective art.”

Co-founder Hilla Rebay, an abstract artist herself, wrote a letter in which she advised Stokes to “learn what is decoration, accident, intellectual confusion, pattern, symmetry… in art there is conceived law only –never an accident.”

A plan for projecting Auroratones in maternity wards to “do away with the pains of child-birth” appears to have been a similar non-starter.

While only one Auroratone is known to have survived – and its discovery by Robert Martens, curator of Grandpa’s Picture Party, is a fascinating tale unto itself – you can try cobbling together a 21st-century DIY approximation by plugging any of the below tunes into your preferred music playing software and turning on the visualizer:

via Boing Boing / INCITE

Related Content

How the 1968 Psychedelic Film Head Destroyed the Monkees & Became a Cult Classic

The Psychedelic Animated Video for Kraftwerk’s “Autobahn” (1979)

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

When Jason Arday became a professor at University of Cambridge at the age of 37, he also became the youngest black person ever appointed to a professorship there. That’s impressive, but it becomes much more so when you consider that he didn’t learn to speak until he was eleven years old and read until he was eighteen. Diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder at the age of three, he had to find different ways to develop himself and his life than most of us, and also to take advantage of help from the right collaborators: his mother, for instance, who learned the value of repetition to the autistic mind, and introduced her son to the highly repetitive game of snooker to get him used to mastering tasks.

“It’s hard to say if it worked or not,” Arday says in the Great Big Story video above. “Well, in terms of snooker, it did, because I became a really good snooker player.” An interested high school teacher, Chris Trace, and later a college tutor named Sandro Sandri, encouraged Arday to use his strong focus to not just catch up with but far surpass the average student.

“I don’t consider myself to be intelligent,” Arday says in the Black in Academia video below, “but I would bet that I’m one of the hardest-working people in the world.” In the Sociology of Education department, he’s directed his own work toward improving the situation of students possessed of similar drive in similarly difficult starting conditions.

Among Arday’s projects, according to the University of Cambridge’s web site, “a book with Dr. Chantelle Lewis (University of Oxford) about the challenges and discrimination faced by neurodiverse populations and students of color,” a program “to support the mental health of young people from ethnic minority backgrounds,” research into “the role of the arts and cultural literacy in effective mental health interventions,” and “a book about Paul Simon’s 1986 album, Graceland, focusing on the ethical dilemmas the singer-songwriter confronted by breaking cultural apartheid in South Africa to involve marginalized black communities in its production.”

Here on Open Culture, we’ve previously featured work on how music has helped autistic young people. It’s certainly helped Arday, who credits certain songs with helping him along in his quest for knowledge and academic credentials. He makes reference to David Bowie’s song “Golden Years,” because “there was a period of five years where it felt like everything I touched turned to gold — and I had another period of five years where it was just really, really difficult.” Overcoming disadvantages seems to have constituted half of Arday’s battle, but no less important, in his telling, has been his subsequent decision to focus on his distinctive set of strengths. Despite the young age at which he made professor, none of this came quickly — but then, he’d been psychologically prepared for that by another of his major musical touchstones: AC/DC’s “It’s a Long Way to the Top (If You Wanna Rock ‘N’ Roll).”

Related content:

“Professor Risk” at Cambridge University Says “One of the Biggest Risks is Being Too Cautious”

The Wisdom & Advice of Maurice Ashley, the First African-American Chess Grandmaster

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Nature doesn’t care if you’re happy, but Yale psychology professor Laurie Santos does.

As Dr. Santos points out during the above appearance on The Well, the goals of natural selection have been achieved as long as humans survive and reproduce, but most of us crave something more to consider life worth living.

With depression rising to near epidemic levels on college campuses and elsewhere, it’s worth taking a look at our ingrained behavior, and maybe making some modifications to boost our happiness levels.

Psychology and the Good Life, Dr. Santos’ massive twice weekly lecture class that actively tackles ways of edging closer to happiness, is the most popular course in Yale’s more than 300-year history.

Do we detect some resistance?

Positive psychology – or the science of happiness – is a pretty crowded field lately, and the overwhelming demand created by great throngs of people longing to feel better has attracted a fair number of grifters willing to impart their proven methodologies to anyone enrolling in their paid online courses.

By contrast, Dr. Santos not only has that Yale pedigree, she also cites other respected academics such as the University of Chicago’s Nicholas Epley, a social cognition specialist who believes undersociality, or a lack of face-to-face engagement, is making people miserable, and Harvard’s Dan Gilbert and the University of Virginia’s Timothy Wilson, who co-authored a paper on “miswanting“, or the tendency to inaccurately predict what will truly result in satisfaction and happiness.

Yale undergrad Mickey Rose, who took Psychology and the Good Life in the spring of 2022 to fulfill a social science credit, told the Yale Daily News that her favorite part of the class was that “everything was cited, everything had a credible source and study to back it up:”

I’m a STEM major and it’s kind of my overall personality type to question claims that I find not very believable. Obviously the class made a lot of claims about money, grades, happiness, that are counterintuitive to most people and to Yale students especially.

With Psychology and the Good Life now available to the public for free on Coursera, even skeptics might consider giving Dr. Santos’ recommended “re-wirement practices” a peek, though be forewarned, you should be prepared to put them into practice before making pronouncements as to their efficacy.

It’s all pretty straightforward stuff, starting with “use your phone to actually be a phone”, meaning call a friend or family member to set up an in person get together rather than scrolling through endless social media feeds.

Other common sense adjustments include looking beyond yourself to help by volunteering, resolving to adopt a glass-is-half-full type attitude, cultivating mindfulness, making daily entries in a gratitude journal, and becoming less sedentary.

(You might also give Dr. Santos’ Happiness Lab podcast a go…)

Things to guard against are measuring your own happiness against the perceived happiness of others and “impact bias” – overestimating the duration and intensity of happiness that is the expected result of some hotly anticipated event, acquisition or change in social standing.

Below Dr. Santos gives a tour of the Good Life Center, an on-campus space that stressed out, socially anxious students can visit to get help putting some of those re-wirement practices into play.

Sign up for Coursera’s 10-week Science of Well-Being course here.

Related Content

The Science of Well-Being: Take a Free Online Version of Yale University’s Most Popular Course

Free Online Psychology & Neuroscience Courses, a subset of our collection, 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities

What Are the Keys to Happiness? Lessons from a 75-Year-Long Harvard Study

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

When André Breton, a leader of the Surrealist movement and author of its first manifesto, wrote that “the problem of woman is the most marvelous and disturbing problem in all the world,” he was not alluding to the unfair lack of recognition experienced by his female peers.

Marquee name Surrealists like Breton, Salvador Dalí, Man Ray, René Magritte, and Max Ernst positioned the women in their circle as muses and symbols of erotic femininity, rather than artists in their own right.

As Méret Oppenheim, subject of a recent retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, is seen remarking at the outset of Behind the Masterpiece‘s introduction to “the fantastic women of Surrealism”, above, it was up to female Surrealists to free themselves of the narrowly defined role society – and their male counterparts – sought to impose on them:

A woman isn’t entitled to think, to express aggressive ideas.

The first artist Behind the Masterpiece profiles needs no introduction. Frida Kahlo is surely one of the best known female artists in the world, a woman who played by her own rules, turning to poetic, often brutal imagery as she delved into her own physical and mental suffering:

I paint self-portraits, because I paint my own reality. I paint what I need to. Painting completed my life. I lost three children and painting substituted for all of this… I am not sick, I am broken. But I am happy to be alive as long as I can paint.

The National Museum of Women in the Arts notes that Remedios Varo – the subject of a current exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago– and Leonora Carrington “were seen as the ‘femmes-enfants’ to the famous and much older male artists in their lives.”

Their friendship was ultimately more satisfying and far longer lasting then their romantic attachments to Surrealist luminaries Ernst and poet Benjamin Péret. Carrington paid tribute to it in her novel, The Hearing Trumpet.

The pair’s work reveals a shared interest in alchemy, astrology and the occult, approaching them from characteristically different angles, as per Stefan van Raay, author of Surreal Friends: Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, and Kati Horna:

Carrington’s work is about tone and color and Varo’s is about line and form.

The name of Dorothea Tanning, like that of Leonora Carrington, is often linked to Max Ernst, though she made no bones about her desire to keep her artistic identity separate from that of her husband of 30 years.

Her work evolved several times over the course of a career spanning seven decades, but her first major museum survey was a posthumous one.

University of Cambridge art history professor, Alyce Mahon, co-curator of that Tate Modern exhibit, touches on the nature of Tanning’s deceptively feminine soft sculptures:

If I asked for two words that you associate with pin cushions, you would say sewing and craft, and you would associate those with the female in the house. Tanning played with the idea of wifely skills and took a very humble object and turned it into a fetish. She crafted her first one out of velvet in 1965 and randomly placed pins in it and aligned it with a voodoo doll. She says it ‘bristles’ with images. So she takes something fabulously familiar and makes it uncanny and strange to encourage us to think differently.

Tanning rejected the label of ‘woman artist’, viewing it as “just as much a contradiction in terms as ‘man artist’ or ‘elephant artist’.”

Put that in your pipe and smoke it, Sigmund Freud!

The famed psychoanalyst’s concept of the subconscious mind was central to Surrealism, but he also wrote that “women oppose change, receive passively, and add nothing of their own.”

One wonders what he would have made of Object, the fur lined teacup, saucer and spoon that is Oppenheim’s best known work, for better or worse.

In an essay for Khan Academy’s AP/College Art History course Josh Rose describes how Museum of Modern Art patrons declared it the “quintessential” Surrealist object when it was featured in the influential 1936-37 exhibition “Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism:”

But for Oppenheim, the prestige and focus on this one object proved too much, and she spent more than a decade out of the artistic limelight, destroying much of the work she produced during that period. It was only later when she re-emerged, and began publicly showing new paintings and objects with renewed vigor and confidence, that she began reclaiming some of the intent of her work. When she was given an award for her work by the City of Basel, she touched upon this in her acceptance speech, (saying,) “I think it is the duty of a woman to lead a life that expresses her disbelief in the validity of the taboos that have been imposed upon her kind for thousands of years. Nobody will give you freedom; you have to take it.”

Related Content

Discover Leonora Carrington, Britain’s Lost Surrealist Painter

A Brief Animated Introduction to the Life and Work of Frida Kahlo

The Forgotten Women of Surrealism: A Magical, Short Animated Film

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

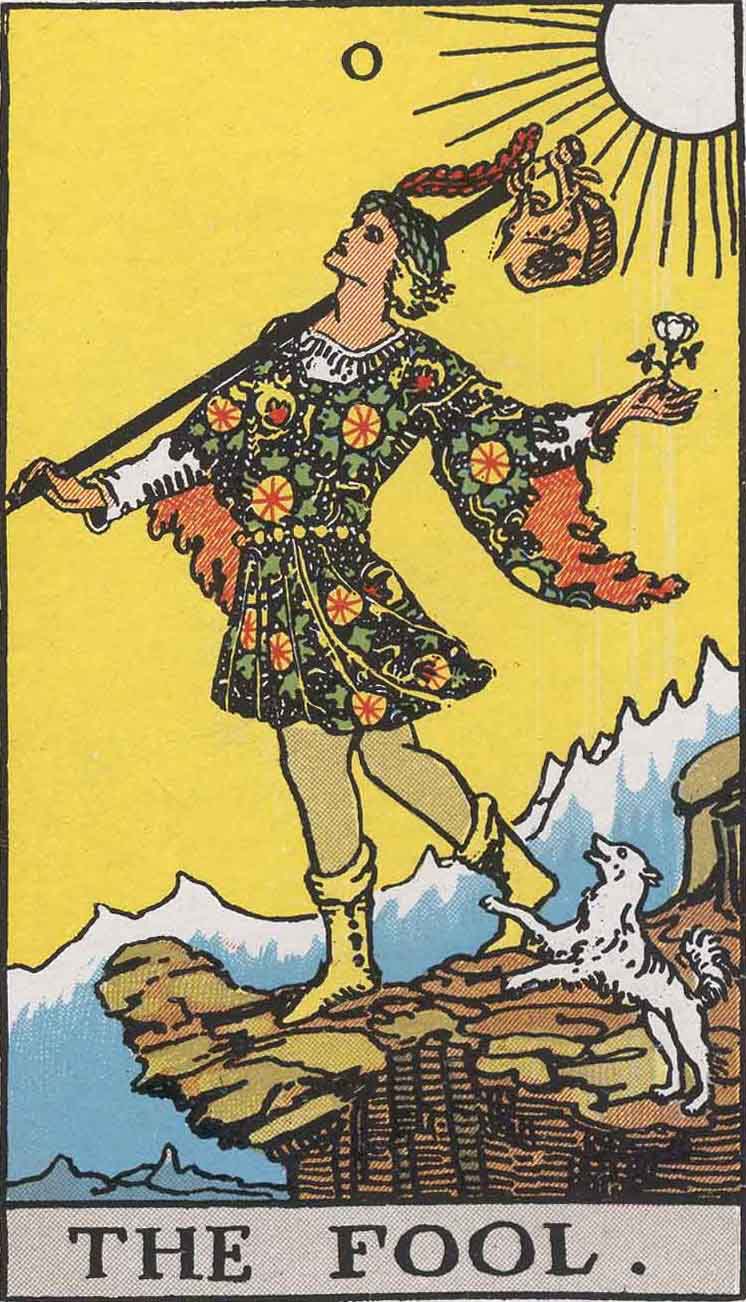

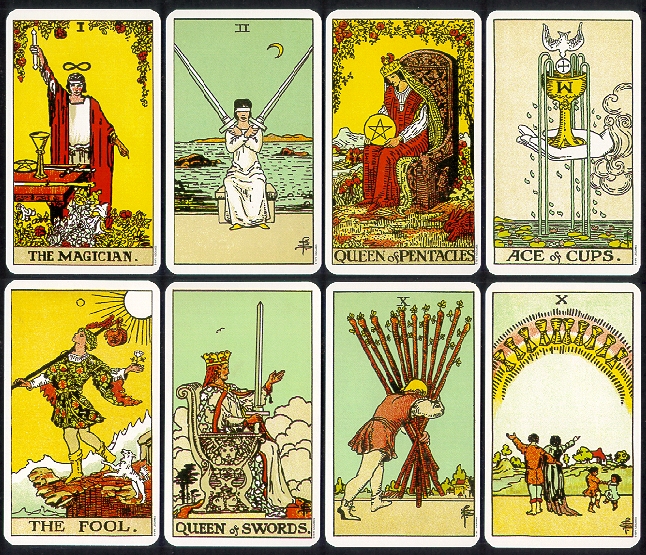

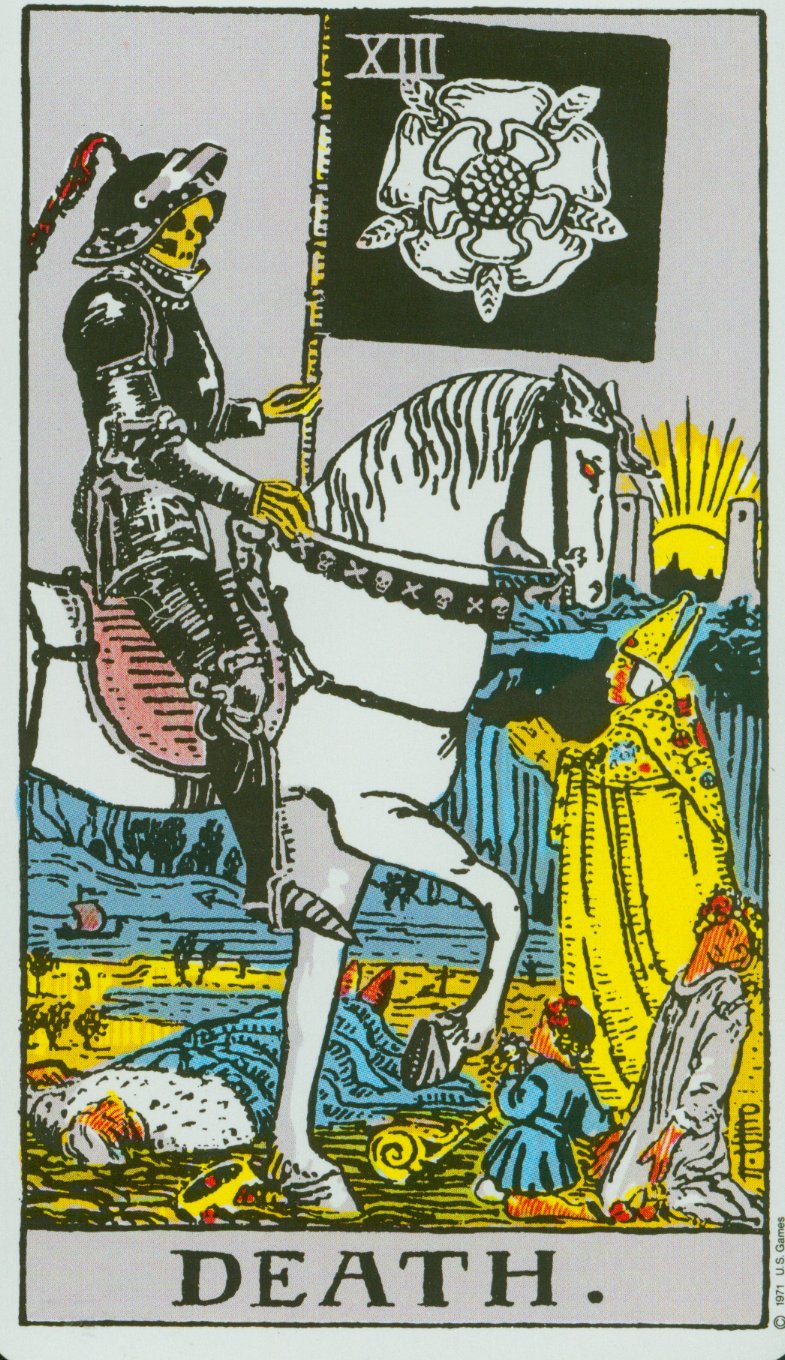

It is generally accepted that the standard deck of playing cards we use for everything from three-card monte to high-stakes Vegas poker evolved from the Tarot. “Like our modern cards,” writes Sallie Nichols, “the Tarot deck has four suits with ten ‘pip’ or numbered cards in each…. In the Tarot deck, each suit has four ‘court’ cards: King, Queen, Jack, and Knight.” The latter figure has “mysteriously disappeared from today’s playing cards,” though examples of Knight playing cards exist in the fossil record. The modern Jack is a survival of the Page cards in the Tarot. (See examples of Tarot court cards here from the 1910 Rider-Waite deck.) The similarities between the two types of decks are significant, yet no one but adepts seems to consider using their Gin Rummy cards to tell the future.

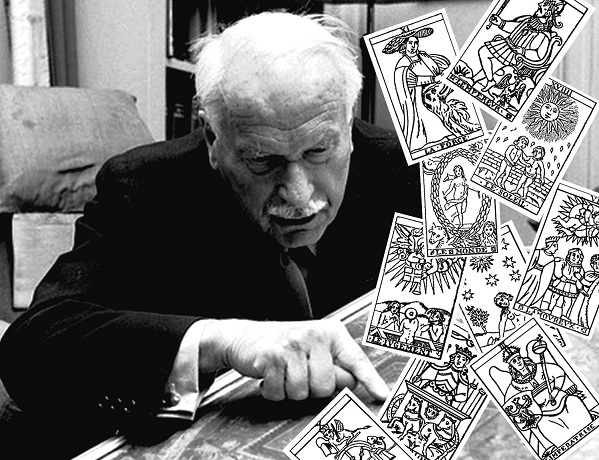

The eminent psychiatrist Carl Jung, however, might have done so.

As Mary K. Greer explains, in a 1933 lecture Jung went on at length about his views on the Tarot, noting the late Medieval cards are “really the origin of our pack of cards, in which the red and the black symbolize the opposites, and the division of the four—clubs, spades, diamonds, and hearts—also belongs to the individual symbolism.

They are psychological images, symbols with which one plays, as the unconscious seems to play with its contents.” The cards, said Jung, “combine in certain ways, and the different combinations correspond to the playful development of mankind.” This, too, is how Tarot works—with the added dimension of “symbols, or pictures of symbolical situations.” The images—the hanged man, the tower, the sun—“are sort of archetypal ideas, of a differentiated nature.”

Thus far, Jung hasn’t said anything many orthodox Jungian psychologists would find disagreeable, but he goes even further and claims that, indeed, “we can predict the future, when we know how the present moment evolved from the past.” He called for “an intuitive method that has the purpose of understanding the flow of life, possibly even predicting future events, at all events lending itself to the reading of the conditions of the present moment.” He compared this process to the Chinese I Ching, and other such practices. As analyst Marie-Louise von Franz recounts in her book Psyche and Matter:

Jung suggested… having people engage in a divinatory procedure: throwing the I Ching, laying the Tarot cards, consulting the Mexican divination calendar, having a transit horoscope or a geometric reading done.

Content seemed to matter much less than form. Invoking the Swedenborgian doctrine of correspondences, Jung notes in his lecture, “man always felt the need of finding an access through the unconscious to the meaning of an actual condition, because there is a sort of correspondence or a likeness between the prevailing condition and the condition of the collective unconscious.”

What he aimed at through the use of divination was to accelerate the process of “individuation,” the move toward wholeness and integrity, by means of playful combinations of archetypes. As another mystical psychologist, Alejandro Jodorowsky, puts it, “the Tarot will teach you how to create a soul.” Jung perceived the Tarot, notes the blog Faena Aleph, “as an alchemical game,” which in his words, attempts “the union of opposites.” Like the I Ching, it “presents a rhythm of negative and positive, loss and gain, dark and light.”

Much later in 1960, a year before his death, Jung seemed less sanguine about Tarot and the occult, or at least downplayed their mystical, divinatory power for language more suited to the laboratory, right down to the usual complaints about staffing and funding. As he wrote in a letter about his attempts to use these methods:

Under certain conditions it is possible to experiment with archetypes, as my ‘astrological experiment’ has shown. As a matter of fact we had begun such experiments at the C. G. Jung Institute in Zurich, using the historically known intuitive, i.e., synchronistic methods (astrology, geomancy, Tarot cards, and the I Ching). But we had too few co-workers and too little means, so we could not go on and had to stop.

Later interpreters of Jung doubted that his experiments with divination as an analytical technique would pass peer review. “To do more than ‘preach to the converted,’” wrote the authors of a 1998 article published in the Journal of Parapsychology, “this experiment or any other must be done with sufficient rigor that the larger scientific community would be satisfied with all aspects of the data taking, analysis of the data, and so forth.” Or, one could simply use Jungian methods to read the Tarot, the scientific community be damned.

As in Jung’s many other creative reappropriations of mythical, alchemical, and religious symbolism, his interpretation of the Tarot inspired those with mystical leanings to undertake their own Jungian investigations into parapsychology and the occult. Inspired by Jung’s verbal descriptions of the Tarot’s major arcana, artist and mystic Robert Wang has created a Jungian Tarot deck, and an accompanying trilogy of books, The Jungian Tarot and its Archetypal Imagery, Tarot Psychology, and Perfect Tarot Divination.

You can see images of each of Wang’s cards here. His books purport to be exhaustive studies of Jung’s Tarot theory and practice, written in consultation with Jung scholars in New York and Zurich. Sallie Nichols’ Jung and Tarot: An Archetypal Journey is less voluminous and innovative—using the traditional, Pamela Coleman-Smith-illustrated, Rider-Waite deck rather than an updated original version. But for those willing to grant a relationship between systems of symbols and a collective unconscious, her book may provide some penetrating insights, if not a recipe for predicting the future.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2017.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content

Carl Jung Offers an Introduction to His Psychological Thought in a 3-Hour Interview (1957)

The Visionary Mystical Art of Carl Jung: See Illustrated Pages from The Red Book

How Carl Jung Inspired the Creation of Alcoholics Anonymous

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

?si=Kq5T7I10zGKJa-bE

These days, psychedelic research is experiencing a renaissance of sorts. And Matt Johnson, a professor of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins, is leading the way. One of “the world’s most published scientists on the human effects of psychedelics,” his research focuses on “unraveling the scientific underpinnings of psychedelic substances, moving beyond their historical and cultural context to shed light on their role in modern therapeutic applications.” Like some other researchers before him, he believes that psychedelics ultimately have the “potential to bring about a paradigm shift in psychiatry, neuroscience, and pharmacology.” In the Big Think video above, the professor answers 24 big questions about psychedelics, from “What are the main effects of psychedelics?,” to “How do psychedelics work in the brain?” and “What are the biggest risks of psychedelics?,” to “Will psychedelics answer the hard problem of consciousness?” Johnson covers a lot of ground here. Settle in. The video runs 2+ hours.

Related Content

Michael Pollan, Sam Harris & Others Explain How Psychedelics Can Change Your Mind

Inside MK-Ultra, the CIA’s Secret Program That Used LSD to Achieve Mind Control (1953-1973)

Aldous Huxley, Psychedelics Enthusiast, Lectures About “the Visionary Experience” at MIT (1962)