Since 1967, the International Board of Books for Young People (IBBY) has celebrated Hans Christian Andersen’s birthday, 2 April, as International Children’s Book Day (ICBD). Celebration aims to inspire a love of reading and to call attention to children’s books.

Each year one of the national bodies of IBBY, sponsors ICBD. Japan is the sponsor for 2024. The theme is “Cross the Seas on the Wings of Imagination”.

This year’s ICBD poster, from IBBY Japan (JBBY), is a collaboration between writer Eiko Kadono and artist Nani Furiya.

Download the poster and flyer to promote this special day.

A special video will be released to members and media.

Friends of the Library Launceston members, have joined IBBY to hold displays of treasured children’s books (including one from 1896), a selection of Libraries Tasmania’s collection of books by Tasmanian children’s authors and three Silent Books. Silent books (wordless picture books) that could be understood and enjoyed by children regardless of language. These books were collected from IBBY National Sections. There are, to date, six collections of Silent Books — you can find them at https://www.ibby.org/awards-activities/activities/silent-books A truly special way to celebrate International Children’s Book Day.

What will you be doing to celebrate?

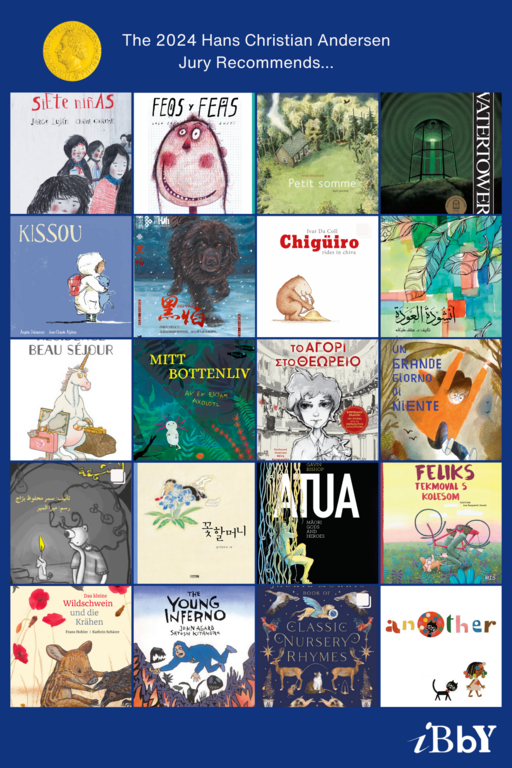

The Hans Christian Andersen Jury, in wanting to help build bridges of understanding, has created a list of twenty outstanding books from the 2024 nominees that they felt were important to merit translation everywhere so that children around the world could read them, thus expanding their access to some of the very best books.

The Watertower by Gary Crew and illustrated by Steven Woolman is on this prestigious list.

IBBY Australia Encouragement Award for a young emerging writer or illustrator

The panel of judges is pleased to announce the shortlists for author and illustrator awards:

Reece Carter, A Girl Called Corpse (Allen & Unwin)

Meg Gatland-Veness, When Only One (Pantera Press)

Jess McGeachin, Kind (Allen & Unwin)

Kirli Saunders, Our Dreaming (Scholastic)

Holden Sheppard, The Brink (Text Publishing)

Rhiannon Williams, Dusty in the Outwilds (Hardie Grant)

Gabriel Evans, A Friend for George (Puffin Books)

Sally Soweol Han, Tiny Wonders (UQP )

Sher Rill Ng, Be Careful, Xiao Xin! (Working Title Press, Harper Collins)

Michelle Pereira, The Boy Who Tried to Shrink His Name (Hardie Grant)

Jeremy Worrall, Etta and the Shadow Taboo (Hardie Grant)

The judges enjoyed reviewing such a diverse range of titles in a variety of genres submitted by publishers of Australia’s emerging writers and illustrators for children and young adults.

Since its inception in 1994, The Ena Noël Award has played a significant role in identifying talented emerging writers and illustrators. Thank you to all the publishers who entered books by young creators for this award. IBBY Australia will announce the winners on International Children’s Book Day (ICBD) 2nd April 2024.

Contact: Claire Stuckey, Coordinator 2024 Ena Noël Award, for any enquiries.

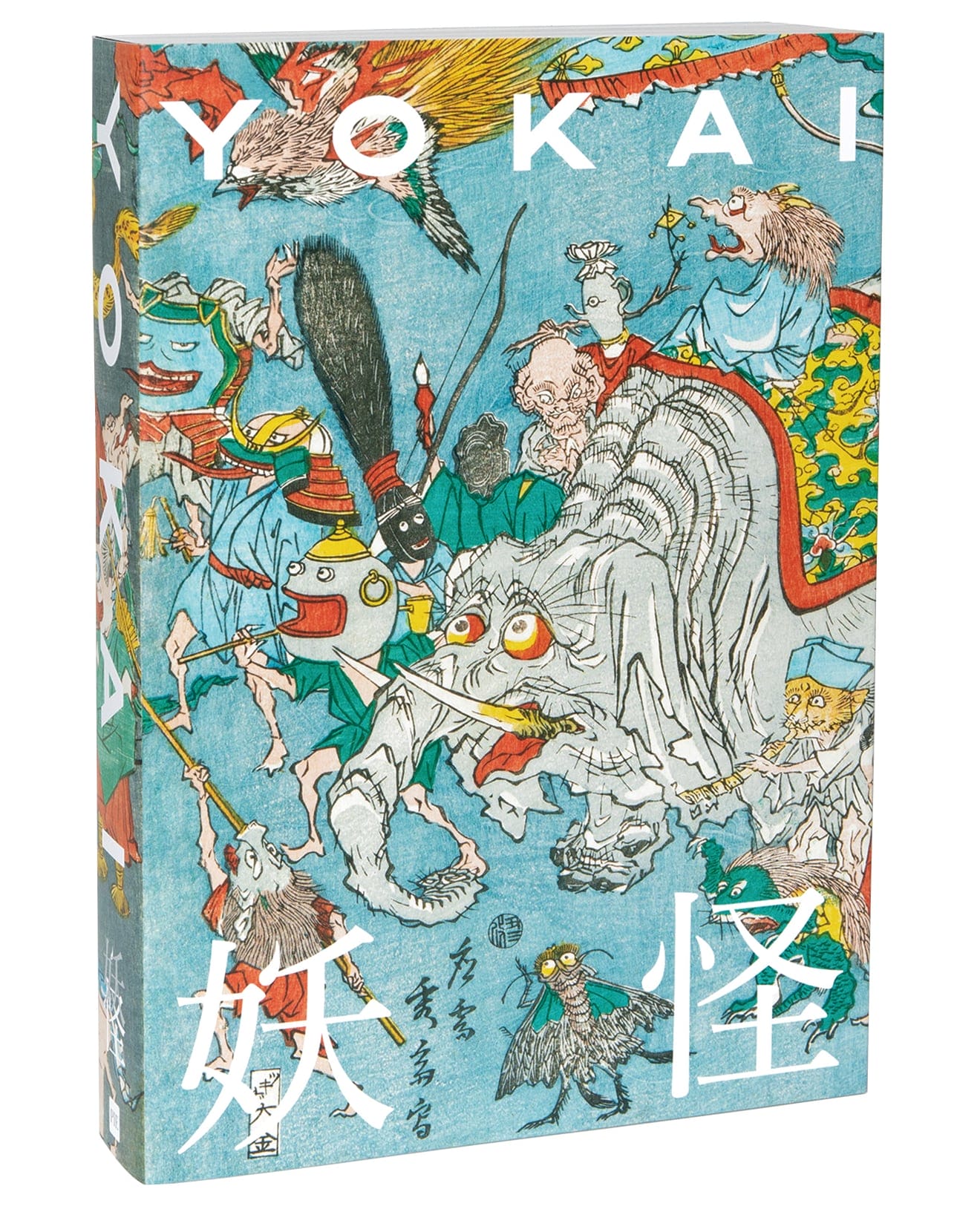

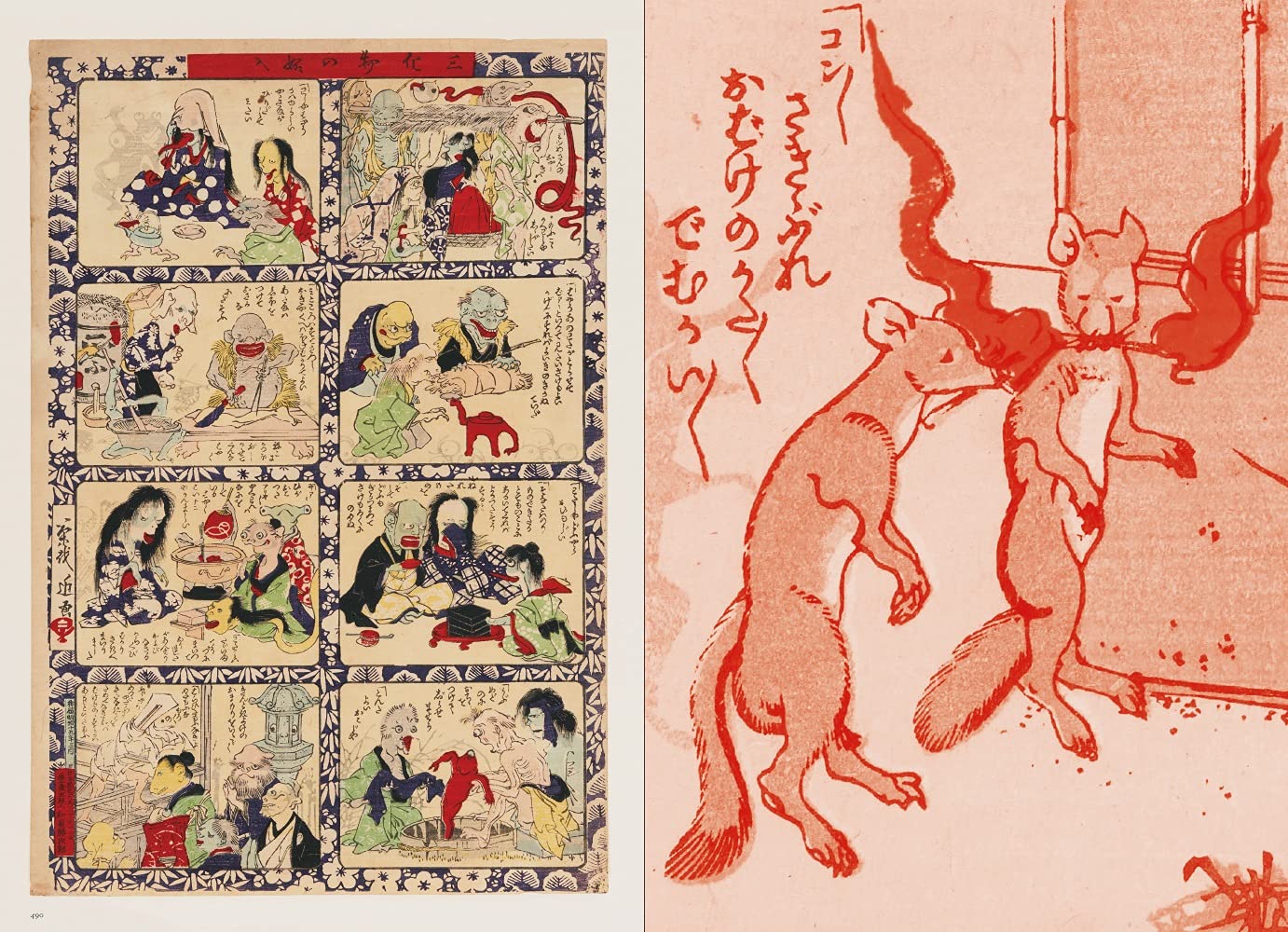

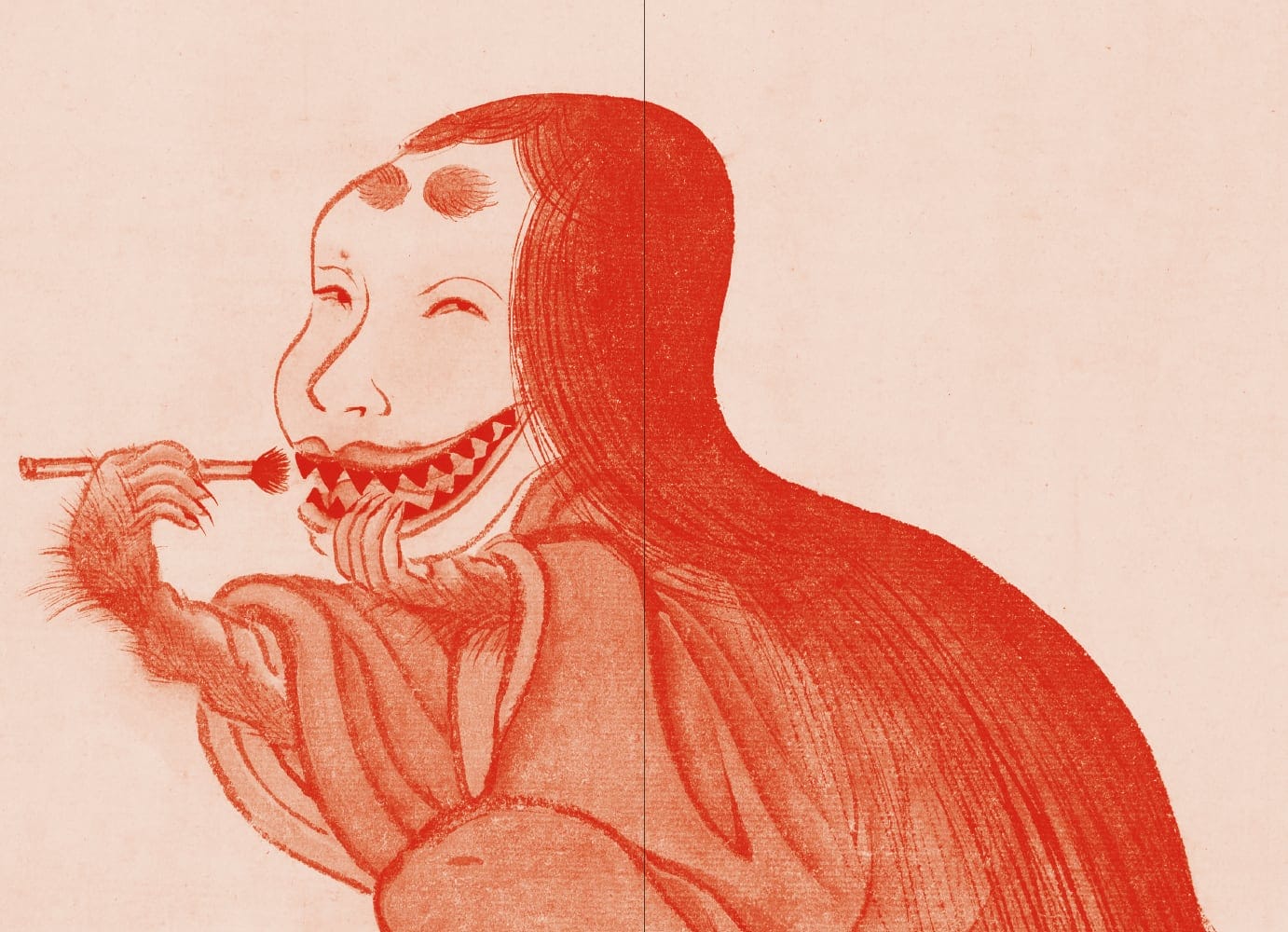

Westerners tend to think of Japan as a land of high-speed trains, expertly prepared sushi and ramen, auteur films, brilliant animation, elegant woodblock prints, glorious old hotels, sought-after jazz-records, cat islands, and ghost towns. The last of those has, of course, not been shown to harbor literal wraiths and spirits. But if that sort of thing happens to be what you’re looking for, Japan’s long history offers up a wealth of mythological chimeras whose form, behavior, and sheer numbers exceed any of our expectations. Welcome to the supernatural realm of the shapeshifting, good- and bad-luck-bringing, trick-playing yōkai.

“Translating to ‘strange apparition,’ the Japanese word yōkai refers to supernatural beings, mutant monsters, and spirits,” writes Colossal’s Grace Ebert. “Mischievous, generous, and sometimes vengeful, the creatures are rooted in folklore and experienced a boom during the Edo period when artists would ascribe inexplicable phenomena to the unearthly characters.”

Hiroshima Prefecture’s Miyoshi Mononoke Museum, whose opening we announced here on Open Culture in 2019, “houses the largest yōkai collection in the world with more than 5,000 works, and a book recently published by PIE International showcases some of the most iconic and bizarre pieces from the institution.”

Written by ethnologist Yumoto Koichi, a yōkai expert whose donations constitute most of the Miyoshi Mononoke Museum’s collection, the 500-page YOKAI offers “the rare experience of seeing the brushwork of Edo-era painters like Tsukioka Yoshitoshi,” whom we’ve featured here as Japan’s last great woodblock artist. Poised between the human and animal kingdoms, reflecting the ways of the past as well as the forces of nature, yōkai would seem to belong entirely to the tales of a bygone age. But in fact, many of them have joined the canon since Tsukioka’s time, having emerged from haunted-school rumors, the fertile imaginations of manga artists, and even video games. Whether to accept these “modern yōkai” has been a matter of some debate, but as Japanese popular culture has long shown us, every age needs its own monsters.

via Colossal

Related content:

The First Museum Dedicated to Japanese Folklore Monsters Is Now Open

When a UFO Came to Japan in 1803: Discover the Legend of Utsuro-bune

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

The Codex Seraphinianus is not a medieval book; nor does it date from the Renaissance along with the codices of Leonardo. In fact, it was published only in 1981, but in the intervening decades it has gained recognition as “the strangest book ever published,” as we described it when we previously featured it here on Open Culture a few years ago. Since then, Rizzoli has published a fortieth-anniversary edition of the Codex, which author-artist Luigi Serafini has granted interviews to promote. What new light has thus been shed on its more than 400 pages filled with bizarre illustrations and indecipherable text?

“The book is designed to be completely alien to anybody who picks it up,” says the narrator of the Curious Archive video at the top of the post. “Not only are the images utterly mind-bending, it’s written in a made-up and thoroughly untranslatable language. And yet, the more you read, the more you might find a strange sense of continuity among the images. That’s because Serafini intended this book to be an encyclopedia: an encyclopedia of a world that doesn’t exist.”

The experience of reading it — if “reading” be the word — “reminds me of being young and flipping through an encyclopedia, staring at pictures and not comprehending the words, but feeling a strange, untranslatable world hovering just outside my understanding.”

Serafini himself describes the Codex as “an attempt to describe the imaginary world in a systematic way” in the Great Big Story video above. To create it, he spent two and a half years in a state he likens to “going in a trance,” drawing all these “fish with eyes or double rhinoceroses and whatever.” These images came first, and they were all so strange that he “had to find a language to explain” them. The resulting experience lets us experience what it is “to read without knowing how to read” — an experience that has attracted the attention of thinkers from Douglas Hofstadter to Roland Barthes to Serafini’s countryman Italo Calvino, a man possessed of no scant interest in the strange, mythical, and inscrutable.

In a 1982 essay, Calvino writes of Serafini’s “very clear italics,” which “we always feel we are just an inch away from being able to read and yet which elude us in every word and letter. The anguish that this Other Universe conveys to us does not stem so much from its difference to our world as from its similarity.” Clearly, “Serafini’s universe is inhabited by freaks. But even in the world of monsters there is a logic whose outlines we seem to see emerging and vanishing, like the meanings of those words of his that are diligently copied out by his pen-nib.” It all brings to mind a joke I once heard that likens humanity, with its invincible instinct to ask what everything means, to a race of space aliens with enormous trunks. When these aliens visit Earth, they respond to everything we try to tell them with the same question: “Yes, but what does that have to do with trunks?”

Related content:

An Introduction to the Codex Seraphinianus, the Strangest Book Ever Published

Wonderfully Weird & Ingenious Medieval Books

Carl Jung’s Hand-Drawn, Rarely-Seen Manuscript The Red Book: A Whispered Introduction

The Meaning of Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights Explained

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

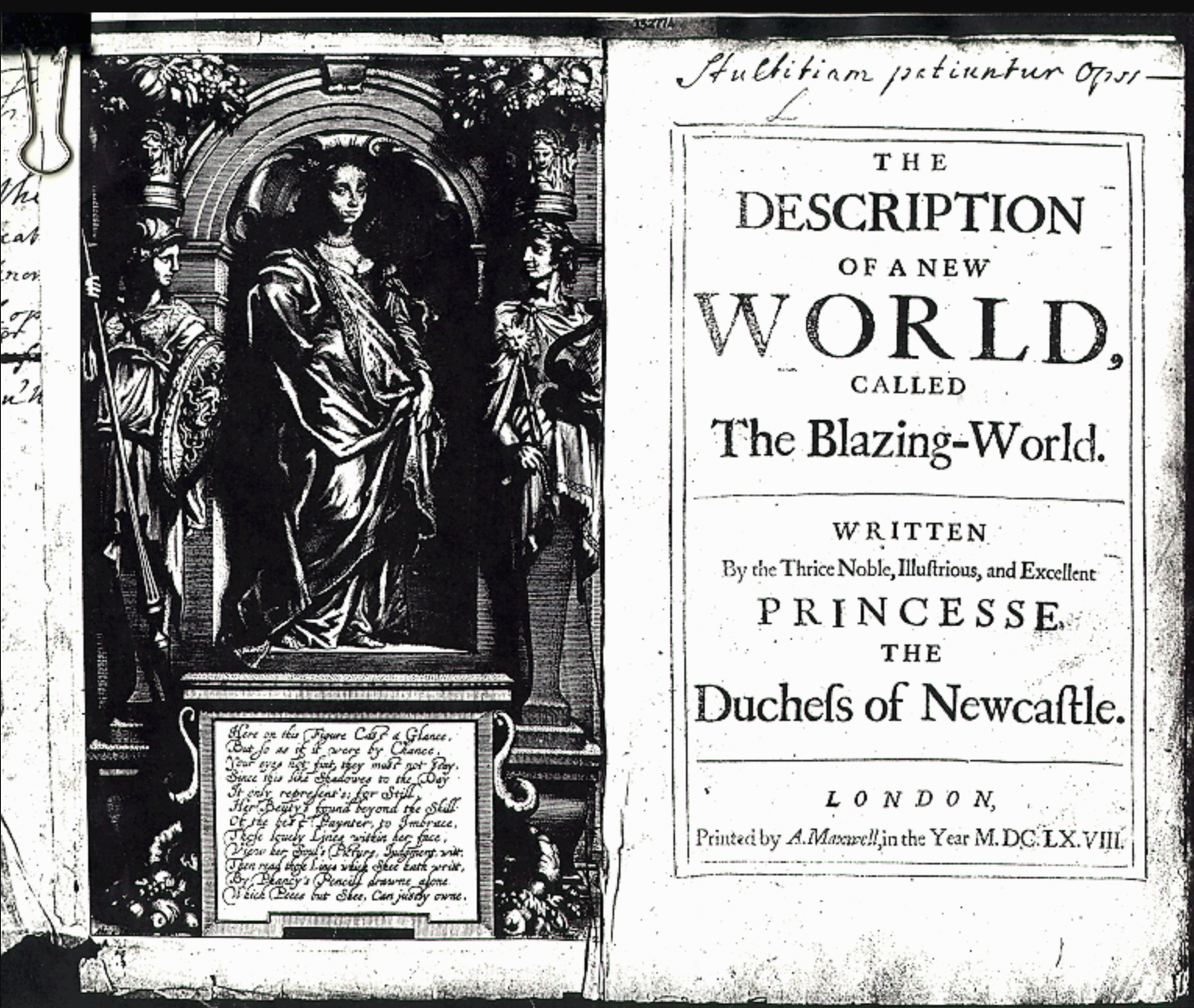

For a variety of reasons, science fiction has long been regarded as a mostly male-oriented realm of literature. This is evidenced, in part, by the eagerness to celebrate particular works of sci-fi written by women, like Ursula K. LeGuin’s Earthsea saga, Octavia Butler’s Parable novels, Joanna Russ’ The Female Man, or Margaret Attwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (uneasily though it fits within the boundaries of the genre). But those who prefer the early stuff can go all the way back to the mid-seventeenth century, where they’ll find Margaret Cavendish’s The Blazing World, readable and downloadable in all its strange glory free online.

“The Blazing World was first published in 1666 and is often considered a forerunner to both science fiction and the utopian novel genres,” writes book blogger Eric Karl Anderson. “It’s a totally bonkers story of a woman who is stolen away to the North Pole only to find herself in a strange bejeweled kingdom of which she becomes the supreme Empress. Here she consults with many different animal/insect people about philosophical, religious and scientific ideas. The second half of the book pulls off a meta-fictional trick where Cavendish (as the Duchess of Newcastle) enters the story herself to become the Empress’ scribe and close companion.”

In the video just below, Youtuber Great Books Prof frames this as not just a work of proto-science fiction, but also a pioneering use of the “multiverse” concept that has undergirded any number of twenty-first-century blockbusters.

The Blazing World continues to inspire: actor-director Carlson Young put out a loose cinematic adaptation just a few years ago. Cavendish herself described the book as a “hermaphroditic text,” possibly in reference to its engagement with topics then addressed almost exclusively by men. But it also occupied two categories at once in that she originally published it as a fictional section of her book Observations upon Experimental Philosophy, one of six philosophical volumes she wrote. In fact, her work qualified her as not just philosopher and novelist, but also scientist, poet, playwright, and even biographer. That last she accomplished by writing The Life of the Thrice Noble, High and Puissant Prince William Cavendish, who happened to be her husband. Let her life be a lesson to those young girls who simultaneously dream of becoming a princess and a writer whose books are read for centuries: sometimes, you can have it all.

Related content:

100 Great Sci-Fi Stories by Women Writers (Read 20 for Free Online)

The First Work of Science Fiction: Read Lucian’s 2nd-Century Space Travelogue A True Story

When Astronomer Johannes Kepler Wrote the First Work of Science Fiction, The Dream (1609)

The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction: 17,500 Entries on All Things Sci-Fi Are Now Free Online

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

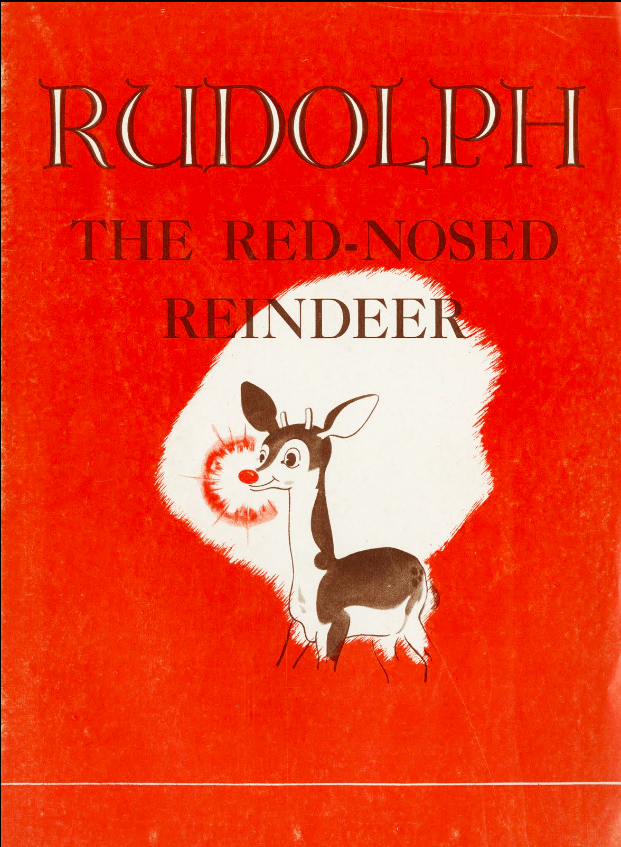

It’s time to forget nearly everything you know about Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer…at least as established by the 1964 Rankin/Bass stop motion animated television special.

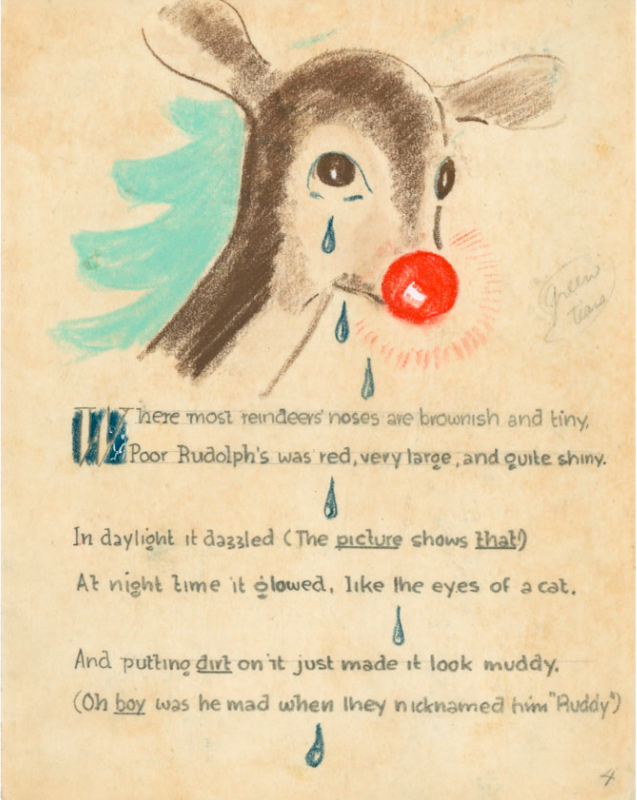

You can hang onto the source of Rudolph’s shame and eventual triumph — the glowing red nose that got him bounced from his playmates’ reindeer games before saving Christmas.

Lose all those other now-iconic elements — the Island of Misfit Toys, long-lashed love interest Clarice, the Abominable Snow Monster of the North, Yukon Cornelius, Sam the Snowman, and Hermey the aspirant dentist elf.

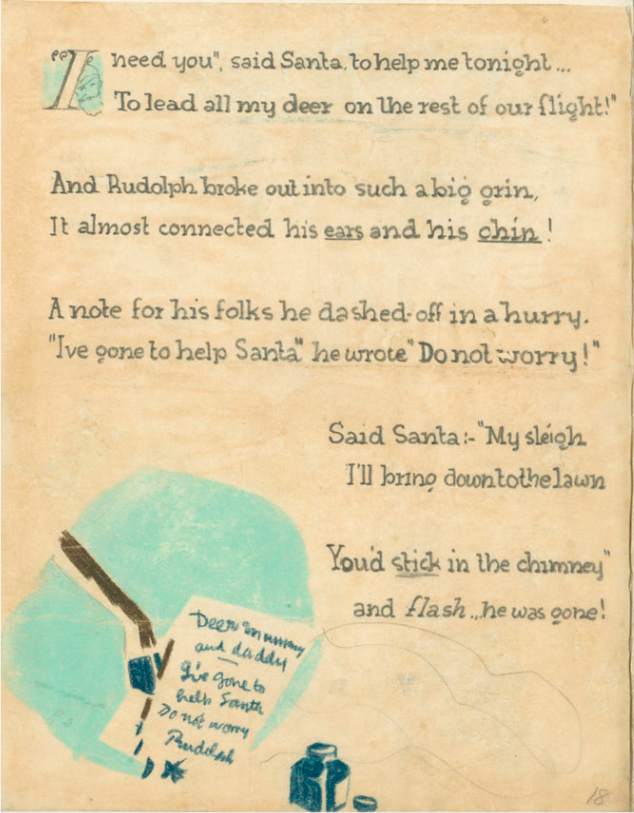

As originally conceived, Rudolph (runner up names: Rollo, Rodney, Roland, Roderick and Reginald) wasn’t even a resident of the North Pole.

He lived with a bunch of other reindeer in an unremarkable house somewhere along Santa’s delivery route.

Santa treated Rudolph’s household as if it were a human address, coming down the chimney with presents while the occupants were asleep in their beds.

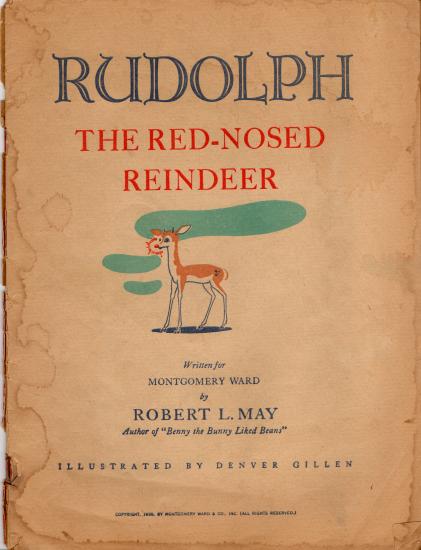

To get to Rudolph’s origin story we must travel back in time to January 1939, when a Montgomery Ward department head was already looking for a nationwide holiday promotion to draw customers to its stores during the December holidays.

He settled on a book to be produced in house and given away free of charge to any child accompanying their parent to the store.

Copywriter Robert L. May was charged with coming up with a holiday narrative starring an animal similar to Ferdinand the Bull.

After giving the matter some thought, May tapped Denver Gillen, a pal in Montgomery Ward’s art department, to draw his underdog hero, an appealing-looking young deer with a red nose big enough to guide a sleigh through thick fog.

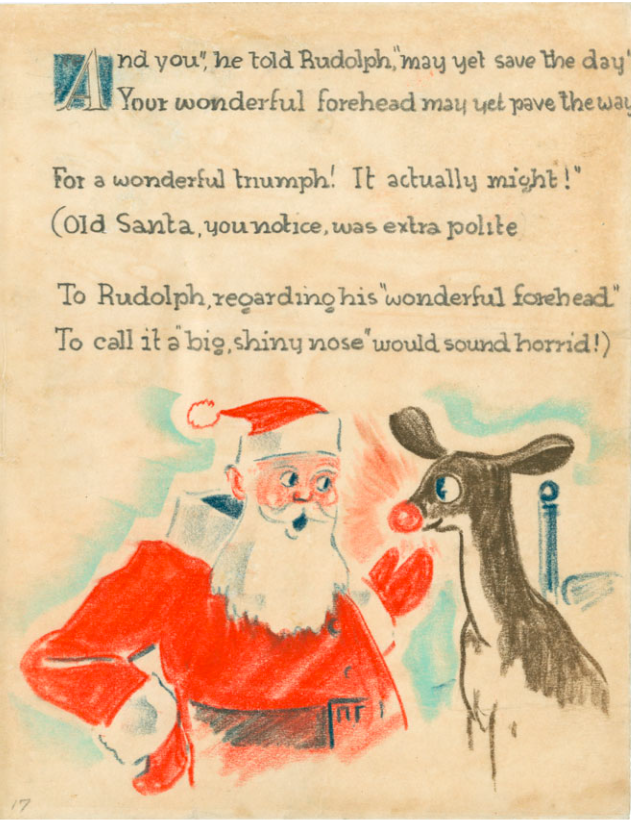

(That schnozz is not without controversy. Prior to Caitlin Flanagan’s 2020 essay in the Atlantic chafing at the television special’s explicitly cruel depictions of othering the oddball, Montgomery Ward fretted that customers would interpret a red nose as drunkenness. In May’s telling, Santa is so uncomfortable bringing up the true nature of the deer’s abnormality, he pretends that Rudolph’s “wonderful forehead” is the necessary headlamp for his sleigh…)

On the strength of Gillen’s sketches, May was given the go-ahead to write the text.

His rhyming couplets weren’t exactly the stuff of great children’s literature. A sampling:

Twas the day before Christmas, and all through the hills,

The reindeer were playing, enjoying the spills.

Of skating and coasting, and climbing the willows,

And hopscotch and leapfrog, protected by pillows.

___

And Santa was right (as he usually is)

The fog was as thick as a soda’s white fizz

—-

The room he came down in was blacker than ink

He went for a chair and then found it a sink!

No matter.

May’s employer wasn’t much concerned with the artfulness of the tale. It was far more interested in its potential as a marketing tool.

“We believe that an exclusive story like this aggressively advertised in our newspaper ads and circulars…can bring every store an incalculable amount of publicity, and, far more important, a tremendous amount of Christmas traffic,” read the announcement that the Retail Sales Department sent to all Montgomery Ward retail store managers on September 1, 1939.

Over 800 stores opted in, ordering 2,365,016 copies at 1½¢ per unit.

Promotional posters touted the 32-page freebie as “the rollickingest, rip-roaringest, riot-provokingest, Christmas give-away your town has ever seen!”

The advertising manager of Iowa’s Clinton Herald formally apologized for the paper’s failure to cover the Rudolph phenomenon — its local Montgomery Ward branch had opted out of the promotion and there was a sense that any story it ran might indeed create a riot on the sales floor.

His letter is just but one piece of Rudolph-related ephemera preserved in a 54-page scrapbook that is now part of the Robert Lewis May Collection at Dartmouth, May’s alma mater.

Another page boasts a letter from a boy named Robert Rosenbaum, who wrote to thank Montgomery Ward for his copy:

I enjoyed the book very much. My sister could not read it so I read it to her. The man that wrote it done better than I could in all my born days, and that’s nine years.

The magic ingredient that transformed a marketing scheme into an evergreen if not universally beloved Christmas tradition is a song …with an unexpected side order of corporate generosity.

May’s wife died of cancer when he was working on Rudolph, leaving him a single parent with a pile of medical bills. After Montgomery Ward repeated the Rudolph promotion in 1946, distributing an additional 3,600,000 copies, its Board of Directors voted to ease his burden by granting him the copyright to his creation.

Once he held the reins to the “most famous reindeer of all”, May enlisted his songwriter brother-in-law, Johnny Marks, to adapt Rudolph’s story.

The simple lyrics, made famous by singing cowboy Gene Autry’s 1949 hit recording, provided May with a revenue stream and Rankin/Bass with a skeletal outline for its 1964 stop-animation special.

Screenwriter Romeo Muller, the driving force behind the Island of Misfit Toys, Sam the Snowman, Clarice, et al revealed that he would have based his teleplay on May’s original book, had he been able to find a copy.

Read a close-to-final draft of Robert L. May’s Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, illustrated by Denver Gillen here.

Bonus content: Max Fleischer’s animated Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer from 1948, which preserves some of May’s original text.

Related Content

Hear Neil Gaiman Read A Christmas Carol Just Like Charles Dickens Read It

Hear Paul McCartney’s Experimental Christmas Mixtape: A Rare & Forgotten Recording from 1965

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

1. Digital Book

2. Bubok

3. eBiblio

4. Textos.info

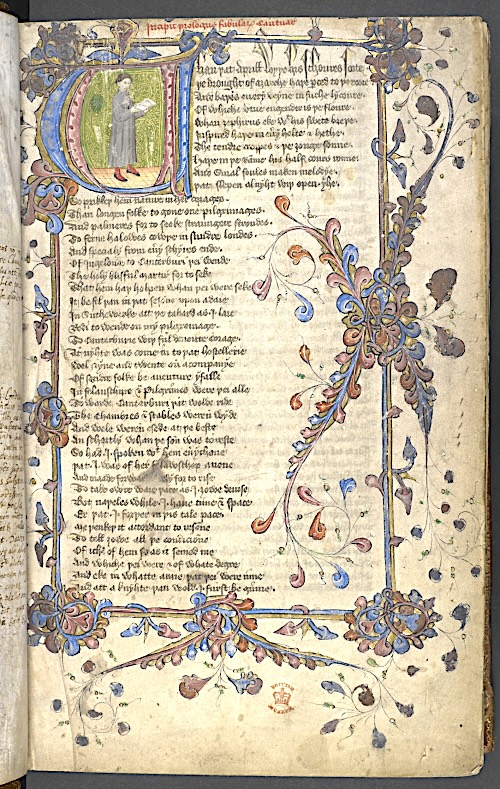

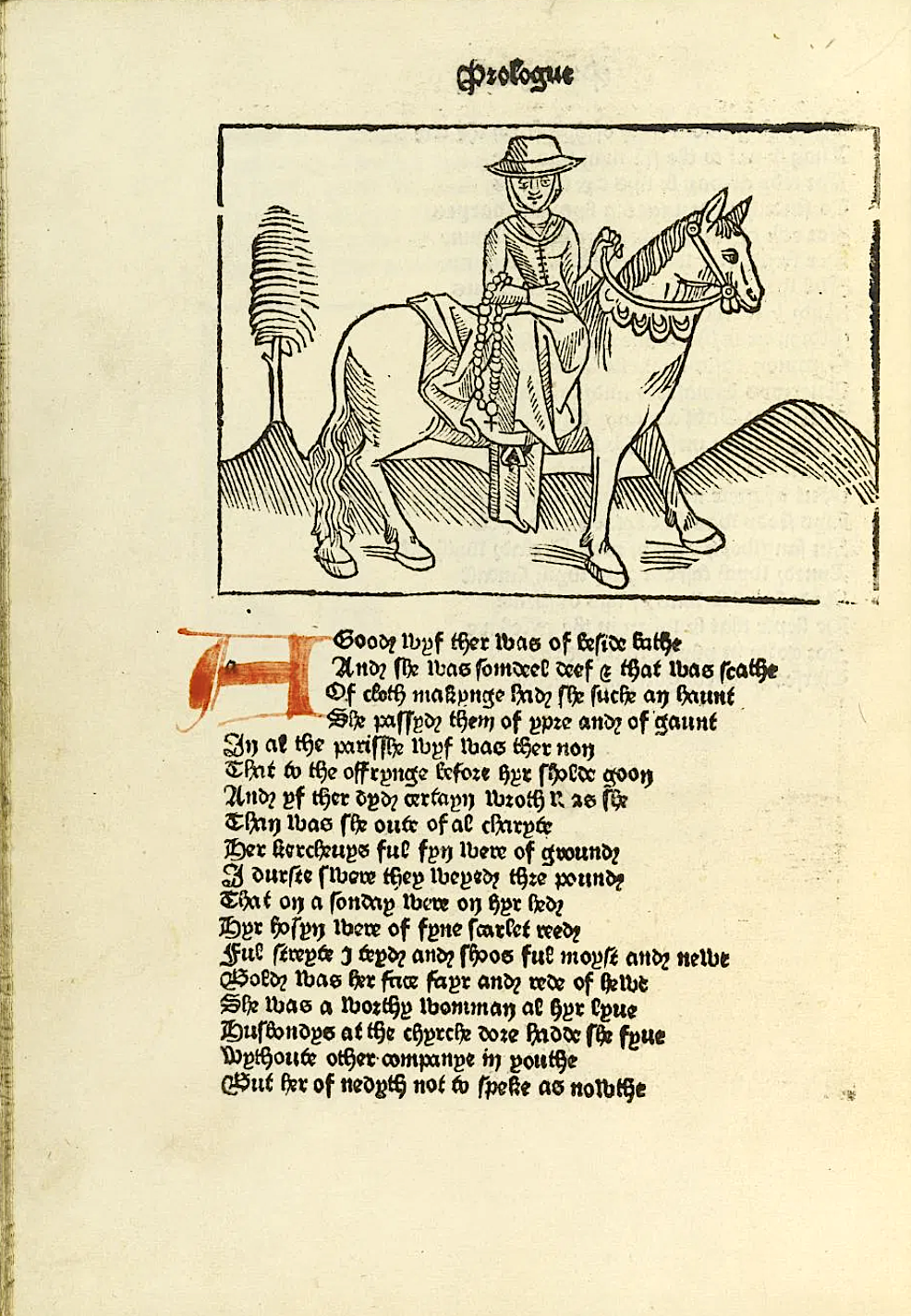

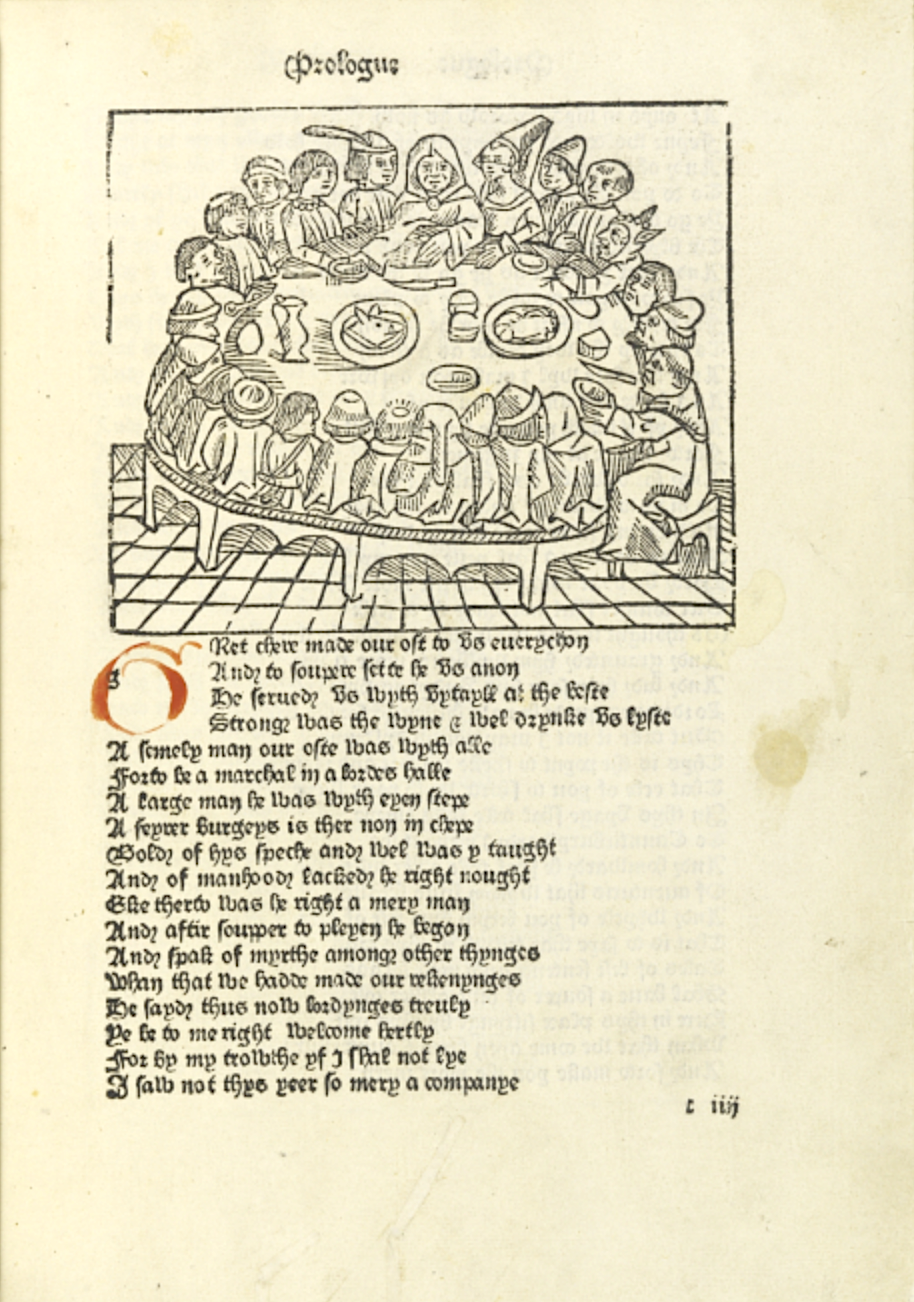

Earlier this year, Oxford professor of English literature Marion Turner published The Wife of Bath: A Biography. Even if you don’t know anything about that book’s subject, you’ve almost certainly heard of her, and perhaps also of her traveling companions like the Knight, the Summoner, the Nun’s Priest, and the Canon’s Yeoman. These are just a few of the pilgrims whose storytelling contest structures Geoffrey Chaucer’s fourteenth-century magnum opus The Canterbury Tales, whose influence continues to reverberate through English literature, even all these centuries after the author’s death. In commemoration of the 623rd anniversary of that work, the British Library has opened a vast online Chaucer archive.

This archive comes as a culmination of what the Guardian‘s Caroline Davies describes as “a two and a half year project to upload 25,000 images of the often elaborately illustrated medieval manuscripts.” Among these artifacts are “complete copies of Chaucer’s poems but also unique survivals, including fragmentary texts found in Middle English anthologies or inscribed in printed editions and incunabula (books printed before 1501).”

If you’re looking for The Canterbury Tales, you’ll find no fewer than 23 versions of it, the earliest of which “was written only a few years after Chaucer’s death in roughly 1400.” Also digitized are “rare copies of the 1476 and 1483 editions of the text made by William Caxton,” now considered “the first significant text to be printed in England.”

Four centuries later, designer-writer-social reformer William Morris collaborated with celebrated painter Edward Burne-Jones to create an edition W. B. Yeats once called “the most beautiful of all printed books“: the Kelmscott Chaucer, previously featured here on Open Culture, which you can also explore in the British Library’s new archive (as least as soon as its ongoing cyber attack-related issues are resolved). As its wider contents reveal, Chaucer was the author of not just The Canterbury Tales but also a variety of other poems, the classical-dream-vision story collection The Legend of Good Women, an instruction manual for an astrolabe, and translations of The Romance of the Rose and The Consolation of Philosophy. And his Trojan epic Troilus and Criseyde may sound familiar, thanks to the inspiration it gave, more than 200 years later, to a countryman by the name of William Shakespeare.

Related content:

Behold a Digitization of “The Most Beautiful of All Printed Books,” The Kelmscott Chaucer

Discover the First Illustrated Book Printed in English, William Caxton’s Mirror of the World (1481)

40,000 Early Modern Maps Are Now Freely Available Online (Courtesy of the British Library)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

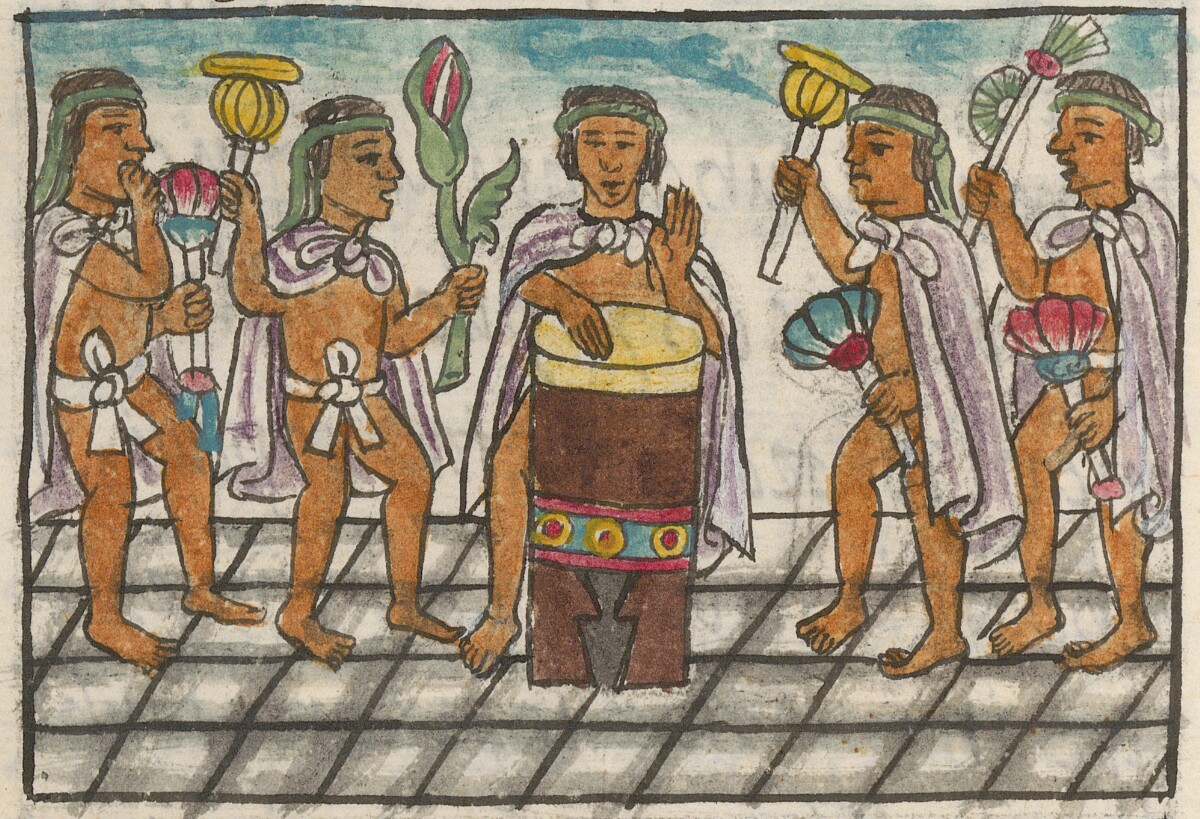

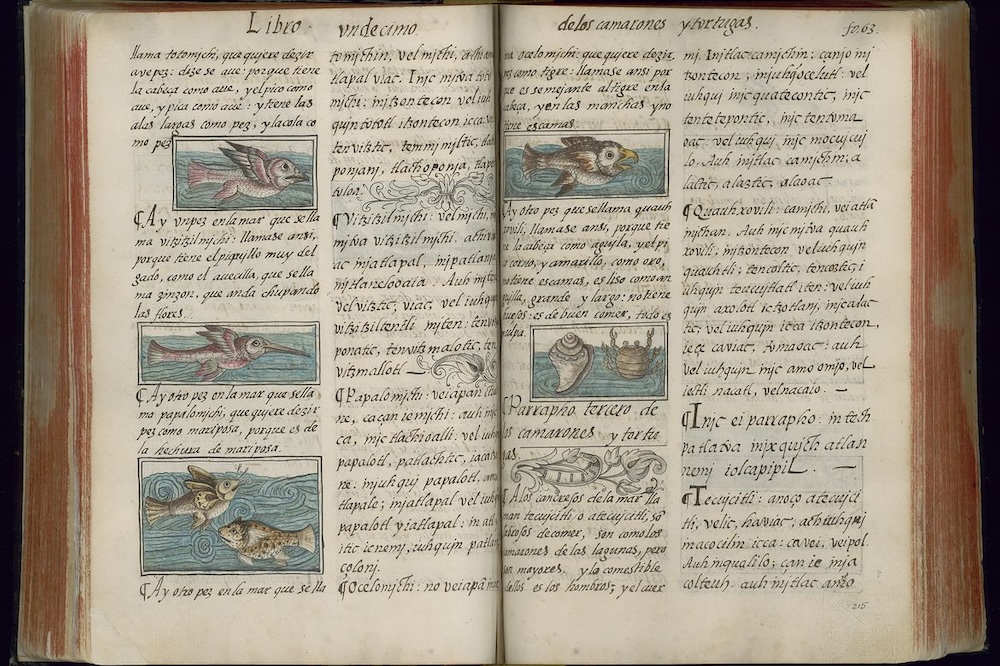

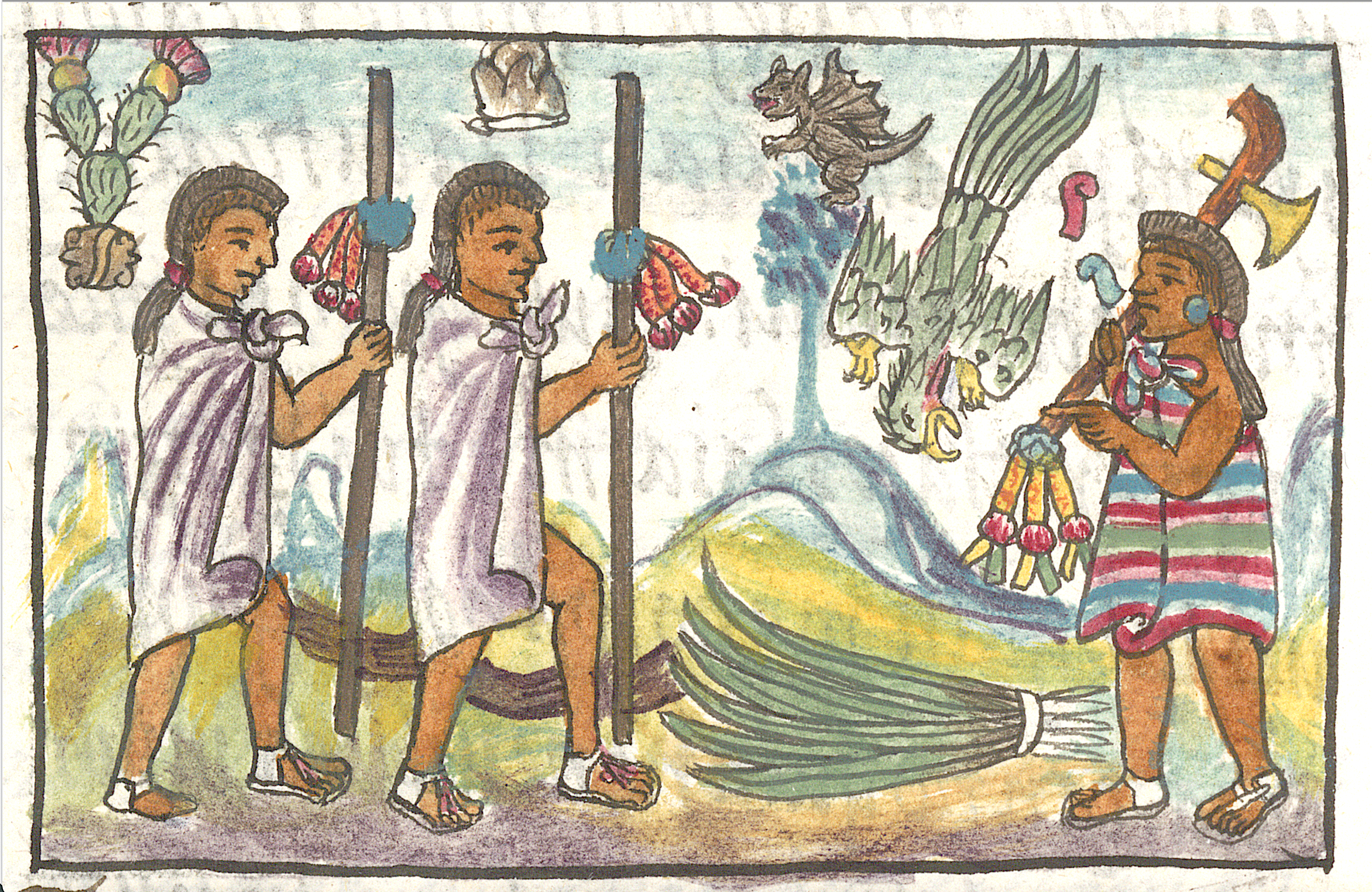

The Spanish conquista of the Americas happened long enough ago — and left behind a spotty enough body of historical records — that we tend to perceive it as much through simplifications, exaggerations, and distortions as we do through facts. What we now call Mexico underwent “essentially an internal conflict between different indigenous groups who saw the arrival of strangers as an opportunity to resist having to pay tribute to the Aztec Empire,” says Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico history professor Berenice Alcántara Rojas. “When the Spaniards initially attacked the Mexica capital, they were swiftly driven out.”

“Only when aided by various groups of Indigenous allies, as well as by the spread of a terrible smallpox epidemic, did they manage to force the ruler Cuauhtemoc and other Mexica leaders to capitulate,” Rojas continues, drawing upon details provided in the version of the events laid out in the Florentine Codex.

That encyclopedic series of twelve 16th-century illustrated manuscripts lavishly documents the known society and nature of that land at the time — and has now, nearly 450 years later, been acknowledged as “the most reliable source of information about Mexica culture, the Aztec Empire, and the conquest of Mexico.”

“In 1547, Bernardino de Sahagún, a Spanish Franciscan friar who committed most of his life to working closely with the Indigenous peoples of Mexico, began collecting information about central Mexican Nahua culture, life, people, history, astronomy, flora, fauna, and the Nahuatl language, among other topics,” says the Getty Research Institute. “Nahua elders, grammarians, scribes, and artists worked with Sahagún to compile a three-volume, 12-book, 2500-page illustrated manuscript, modeling its content on European encyclopedias, especially Pliny the Elder’s Natural History,” all of which has been digitized, translated, and made available at the Getty’s web site.

A thoroughly multicultural project avant la lettre, the Florentine Codex (named for the Medici family library in Florence, where it was sent upon its completion) has only just become accessible to a wide online readership. Though it’s “been digitally available via the World Digital Library since 2012, for most users it remained impenetrable because reading it requires knowledge of sixteenth-century Nahuatl and Spanish, and of pre-Hispanic and early modern European art traditions.” By offering searchable text in modern versions of both those languages as well as English — to say nothing of its browsable sections organized by people, animals, deities, and even by Nahuatl terms like coyote and tortilla — the Digital Florentine Codex re-illuminates an entire civilization.

Related content:

Native Lands: An Interactive Map Reveals the Indigenous Lands on Which Modern Nations Were Built

Explore the Codex Zouche-Nuttall: A Rare, Accordion-Folded Pre-Columbian Manuscript

How the Ancient Mayans Used Chocolate as Money

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

A Secretaria Nacional do Consumidor (Senacon) anunciou que vai multar a Meta em R$ 150 mil para cada dia que a empresa não retirar anúncios fraudulentos relacionados ao Desenrola Brasil do ar no Facebook. A ordem foi dada em 26 de julho, mas não foi cumprida pela big tech, e o valor total é de no mínimo R$ 9,3 milhões.

Leia mais:

Em julho deste ano, a Senacom, vinculada ao Ministério da Justiça, já havia determinado que o Facebook e o Google tirassem as propagandas falsas sobre o Desenrola Brasil, o programa de renegociação de dívidas do governo.

Ambas empresas tiveram 48 horas para remover os anúncios, podendo receber uma multa diária de R$ 140 mil caso não o fizessem.

Além disso, a pasta determinou que as companhias deveriam adotar novas medidas para evitar a circulação de anúncios fraudulentos.

O post Desenrola Brasil: Facebook pode pagar R$ 9,3 milhões por anúncios falsos apareceu primeiro em Olhar Digital.

It can seem that the writing of literature and the theory of literature occupy separate great houses, Game of Thrones-style, or even separate countries held apart by a great sea. Perhaps they war with each other, perhaps they studiously ignore each other or obliquely interact at tournaments with acronymic names like MLA and AWP. Like Thomas Pynchon’s characterization of the political right and left, scholars and writers represent opposing poles, the hothouse and the street. That rare beast, the academic poet, can seem like something of a unicorn, or dragon.

…Or like the ominous talking raven in Edgar Allan Poe’s most famous of poems.

The divide between theory and practice is a recent development, a product of state budgeting, political brinksmanship, the relentless publishing mills of academia that force scholars to find a pigeonhole and stay there…. In days past, poets and scholar/theorists frequently occupied the same place at the same time—Wallace Stevens, T.S. Eliot, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Percy Shelley, and, of course, Poe, whose perennially popular “The Raven” serves as a point-by-point illustration for his theory of composition just as thoroughly as Eliot’s great works bear out his notion of the “objective correlative.”

Poe’s object, the titular creature, is an “archetypal symbol,” writes Dana Gioia, in a poem that aims for what its author calls a “unity of effect.” In his 1846 essay “The Philosophy of Composition,” Poe the poet/theorist tells us in great detail how “The Raven” satisfies all of his other criteria for literature as well, such as achieving its intent in a single sitting, using a repeated refrain, and so on.

Should we have any doubt about how much Poe wanted us to see the poem as the deliberate outcome of a conceptual scheme, we find him three years later, in 1849, the year of his death, delivering a lecture on the “Poetic Principle,” and concluding with a reading of “The Raven.”

John Moncure Daniel of the Richmond Semi-Weekly Examiner remarked after attending one of these talks that “the attention of many in this city is now directed to this singular performance.” At that point, Poe, who hardly made a dime from “The Raven,” had to suffer the indignity of having all of his work go out of print during his brief, unhappy lifetime. Moncure and the Examiner thereby furnished readers “with the only correct copy ever published,” previous appearances, it seems, having contained punctuation errors.

Nonetheless, for all of Poe’s pedantry and penury, “The Raven”‘s first appearances made him semi-famous. His readings were a sensation, and it’s a sure bet that his audiences came to hear him read the poem, not deliver a lecture on its principles. Oh, for some proto-Edison in the room with an early recording device. What would it be like to hear the mournful, grief-stricken, alcoholic genius—master of the macabre and inventor of the detective story—intone the raven’s enigmatic “Nevermore”?

While Poe’s speaking voice has receded irretrievably into history, his poetic voice may live close to forever. So mesmerizing are his meter and diction that many great actors known especially for their voices have become possessed by “The Raven.”

Likely when we think of the poem, what first comes to the mind’s ear is the voice of Vincent Price, or James Earl Jones, Christopher Lee, or Christopher Walken, all of whom have given “The Raven” its due.

And so have many other notables, such as the great Stan Lee, Poe successor Neil Gaiman, original Gomez Addams actor John Astin, and venerable Beat poet/scholar Anne Waldman (listen here). You will find those recitations here at this round-up of notable “Raven” readings, and if this somehow doesn’t satiate you, then check out Lou Reed’s take on the poem, the Grateful Dead’s musical tribute, “Raven Space,” or a reading in 100 different celebrity impressions.

Finally, we would be remiss not to mention The Simpsons’ James Earl Jones-narrated parody, a worthy teaching tool for distracted young visual learners. Is it a shame that we now think of “The Raven” as a Halloween yarn fit for the Treehouse of Horror or any number of enjoyable exercises in spooky oratory—rather than the theoretical thought experiment its author seemed to intend? Does Poe rotisserie in his grave as Homer snores in a wingback chair? Probably. But as the author told us himself at length, the poem works! It still never fails to excite our morbid curiosity, enchant our gothic sensibility, and maybe send a chill or two down the spine. Maybe we never really needed Poe to explain it to us.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2017. We’re bringing it back for Halloween.

Related Content:

Gustave Doré’s Splendid Illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” (1884)

The Raven: a Pop-up Book Brings Edgar Allan Poe’s Classic Supernatural Poem to 3D Paper Life

A Reading of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” in 100 Celebrity Voices

Edgar Allan Poe’s the Raven: Watch an Award-Winning Short Film That Modernizes Poe’s Classic Tale

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

POWERFUL IMMIGRANT STORIES – IBBY AUSTRALIA’S SELECTIONS FOR INCLUSION IN THE HONOUR LIST 2024

IBBY Australia announces its selection of two extraordinary books to be included in the prestigious biennial IBBY Honour List for 2024.

These books become Australia’s representatives in a travelling exhibition of international titles. The 2024 exhibition will be featured at the IBBY Congress in Trieste, Italy, August 2024, the Frankfurt Book Fair, October 2024, the Bologna Children’s Book Fair 2025, and in many other travelling exhibitions to a variety of countries.

Each of the two books selected this year, powerfully reflect the experiences of immigrants to Australia.

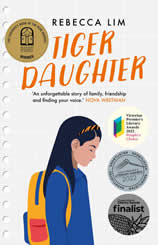

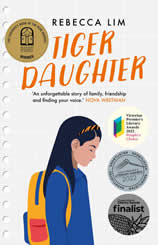

This beautifully crafted novel explores the experiences of Asian immigrants to Australia with wit and authenticity. Wen Zhou is dealing with her father’s overbearing control of their family; helping her friend Henry Xiao develop his English skills; and planning to apply with him for a scholarship to a selective school. But when tragedy strikes the Xiao family, Wen and her mother defy Wen’s father by supporting them.

References to Confucius and other Chinese writers denote philosophical tenets and morals explored in this deeply personal narrative of how Wen seeks to reconcile parental expectations with her contemporary Australian social milieu. Details carry thematic weight, eg. Wen’s mother’s tailored, mended suits present a brittle veneer, camouflaging emotional tensions at home, and her cooking for the Xiaos denotes solace. Heavy themes are explored, such as emotional abuse, mental illness, and grief, but there’s also a lightness to the writing, infused with Wen’s quiet wisdom. Readers are left with the promise that two families have taken steps towards healing, and that for Wen and Henry, all will be well.

Rebecca Lim is an award-winning writer, illustrator and editor and the author of over twenty books, including Tiger Daughter (a CBCA Book of the Year: Older Readers and Victorian Premier’s Literary Award-winner), The Astrologer’s Daughter (A Kirkus Best Book and CBCA Notable Book) and the bestselling Mercy.

Her work has been shortlisted for the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards, NSW Premier’s Literary Awards, Queensland Literary Awards, Margaret and Colin Roderick Literary Award, Foreword INDIES Book of the Year Awards and Isinglass Award, shortlisted multiple times for the Aurealis Awards and Davitt Awards, and longlisted for the Gold Inky Award and David Gemmell Legend Award. Her novels have been translated into German, French, Turkish, Portuguese, Polish and Vietnamese. She co-founded the Voices from the Intersection initiative to support emerging YA and children’s authors and illustrators who are First Nations, People of Colour, LGBTIQA+ and/or living with disability, and co-edited Meet Me at the Intersection, a groundbreaking anthology of YA #OwnVoice memoir, poetry and fiction. Her latest novel is Two Sparrowhawks in a Lonely Sky (2023).

This is an expressive metaphorical exploration of the sacrifices made by immigrant parents for their children to flourish in a new country. The cover depicts a giant child dwarfing his parents; a postage stamp frames the title; endpapers depict teapots from several countries. Told as a fairy tale based on the trope of a bargain – sacrificing centimetres in height each time they give their child what he needs – this is a moving tribute to the parents’ selflessness.

The poetic line: ‘They had old shoes, and empty pockets’ resonates with meaning. The exquisite, muted artwork employs light, shade, and perspective to potent effect, and the metaphor of size is repeated, beginning with an iconic bonsai. Sworder’s inventiveness in format and approach, invested with emotional weight and power, speaks in any language. His technique employs graphite powder, pencils, watercolours, art paper, photo references, and digital technology, and was inspired by Japanese woodblock printmakers, Hokusai and Hiroshige. This universal and timeless story of hope and resilience is a gloriously eloquent paean to Sworder’s parents and to any immigrant.

Zeno Sworder is a Melbourne based writer, artist and picture book maker. He is passionate about literacy, creativity and diversity. He was born into a mixed (Chinese and English) multicultural family in regional Victoria and has worked as a window washer, a dish washer (a step up!), a journalist, an English language teacher, a volunteer for Lifeline, a consular officer and a tribunal advocate for migrants and refugees. But he has always felt most himself sitting at a table drawing pictures and making up stories.

His work has been published in The Age, Meanjin and recognised by the Australia Council for the Arts. His first book, This Small Blue Dot, has been described by the Children’s Book Council of Australia as ‘an example of an insightful contemporary work of art’ and won the CBCA Award for New Illustrator 2021 and Australian Book Design Awards Best Designed Children’s Illustrated Book 2021. My Strange Shrinking Parents won the CBCA Picture Book of the Year Award 2023.

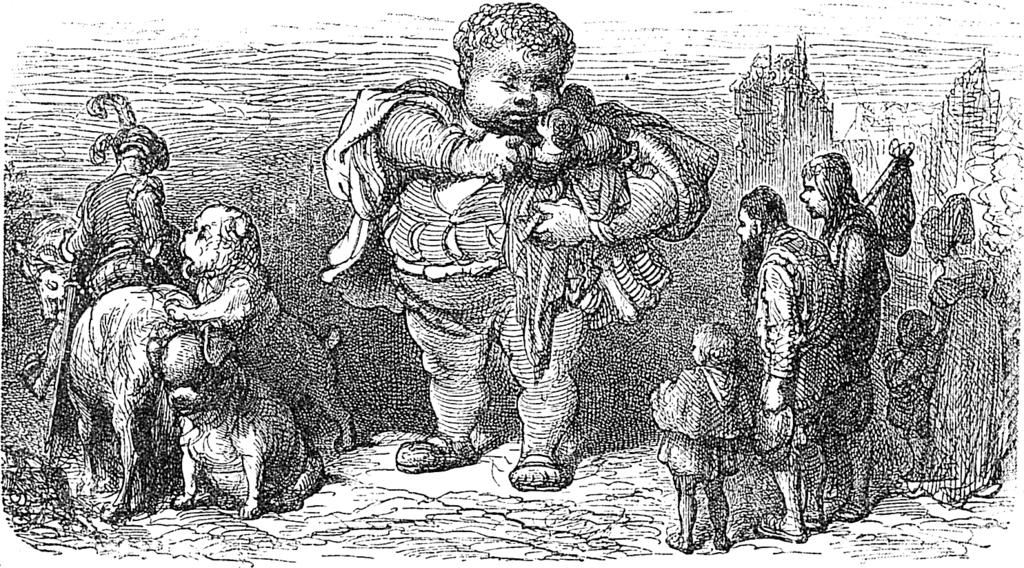

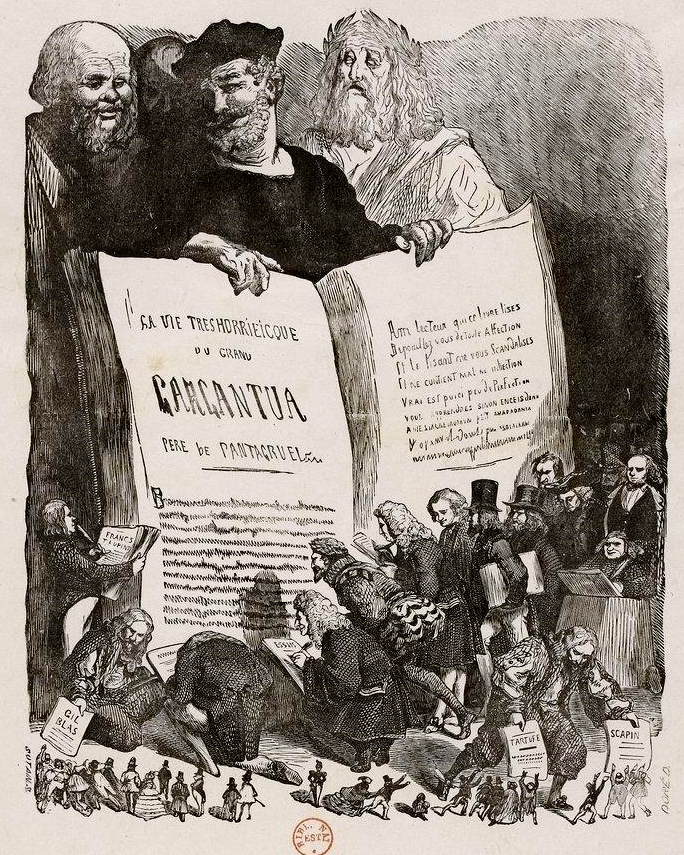

When François Rabelais came up with a couple of giants to put at the center of a series of inventive and ribald works of satirical fiction, he named one of them Gargantua. That may not sound particularly clever today, gargantuan being a fairly common adjective to describe anything quite large. But we actually owe the word itself to Rabelais, or more specifically, to the nearly half-millennium-long legacy of the character into whom he breathed life. But there’s so much more to Les Cinq livres des faits et dits de Gargantua et Pantagruel, or The Five Books of the Lives and Deeds of Gargantua and Pantagruel, whose enduring status as a masterpiece of the grotesque owes much to its author’s wit, linguistic virtuosity, and sheer brazenness.

Nor has it hurt that the books have inspired vivid illustrations from a host of artists, one of whom in particular stands out: Gustave Doré, whom Richard Smyth calls “one of the most prolific — and most successful — book illustrators of the nineteenth century.”

Here at Open Culture, we’ve previously featured the art he created to accompany the work of Dante, Cervantes, and Poe, each a writer possessed of a highly distinctive set of literary powers, and each of whom thus received a different but equally lavish and evocative treatment from Doré.

For Rabelais, says the site of book dealer Heribert Tenschert, the 22-year-old artist produced (in 1854) “100 images that oscillate between the whimsical and the uncanny, between realism and fantasy,” a count he would expand to 700 in another edition two decades later.

You can see a great many of Doré’s illustrations for Gargantua and Pantagruel at Wikimedia Commons. The simultaneous extravagance and repugnance of the series’ medieval France may seem impossibly distant to us, but it can hardly have felt like yesterday to Doré either, given that he was working three centuries after Rabelais.

As suggested by Heribert Tenschert, perhaps these imaginative visions of the Middle Ages — like Balzac’s Rabelaisian Les contes drolatiques, which he also illustrated — “resonated with Doré because they reminded him of the mysterious atmosphere of his childhood, which he had spent in the middle of the medieval city of Strasbourg.” Whatever his connection, Doré created images that still bring to mind a whole range of descriptors: somberly jocular, rigorously voluptuous, compellingly repellent, and above all pantagruelist. (Look it up.)

Related Content:

Gustave Doré’s Exquisite Engravings of Cervantes’ Don Quixote

The Adventures of Famed Illustrator Gustave Doré Presented in a Fantasic(al) Cutout Animation

Gustave Doré’s Dramatic Illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy

Gustave Doré’s Magnificent Illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” (1884)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

We’ve got a thing for creative problem solvers here at Open Culture.

We also love a good community-spirited project.

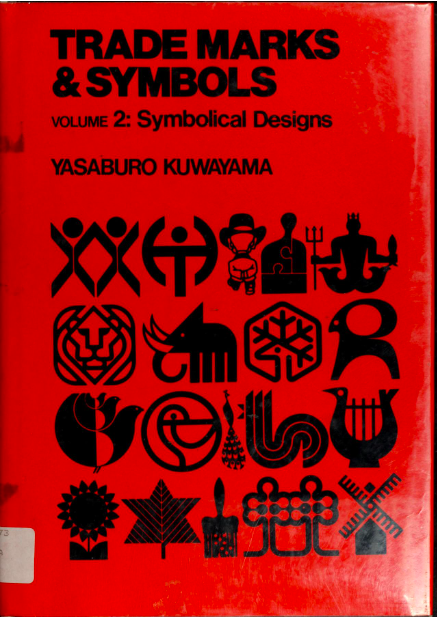

Graphic designer Valery Marier ticks both boxes with archives.design, a free graphic design archive that was born of her frustrations with online research at a time when Covid restrictions shuttered libraries and archives.

The non-profit digital library Internet Archive is rich in interesting material, but its lack of curation can often leave the user feeling like they’re sorting through the world’s most disorganized junk shop, rooting for hidden treasure.

Marier was also discouraged by “a combination of confusing boolean operators and an absolute hodgepodge of different metadata tags and category names:

I figured that if I was having these problems, then there were likely other folks who were as well. So I decided to put my design skills to good use and work on a solution. The biggest issues that I felt needed to be solved were the user experience, and the content curation. For the archive’s curation, I opted to curate each item manually. While I could have likely figured out a way to curate these items using an automated script, I feel that there is an inherent value to human curation. When a collection is curated by a computer it can seem confusing and arbitrary. Whereas with human curation there is often a deliberate connection between each object in the collection. For the navigation I wanted to ensure that it was simple enough that anyone could understand it and operate it. So instead of having a ton of complex operators, I instead decided to organize them by their aspect in design.

Graphic design nerds, rejoice!

Marier determines which of the finds should make the cut by considering relevance and image quality.

A quick peek suggests graphic designers are not the only ones who stand to benefit from this labor of love.

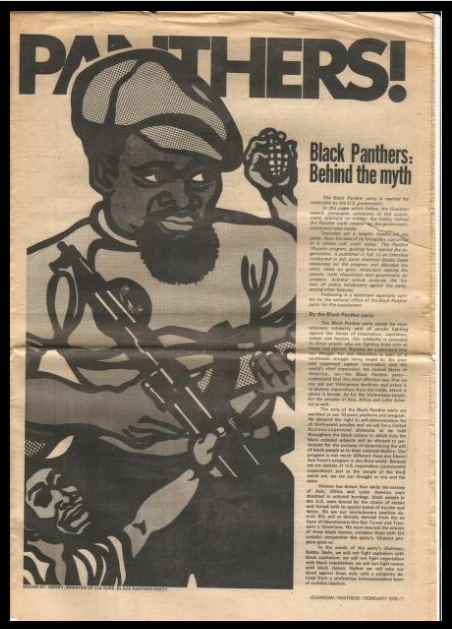

Educators, historians, and activists will be rewarded with a supplement to the Guardian from February 1970, which provided an overview of the Black Panther Party in their own words. There’s a ton of information and history packed into these 8 pages, from its formation and its 10-point program, to an interview with then-incarcerated party chairman Bobby Seale.

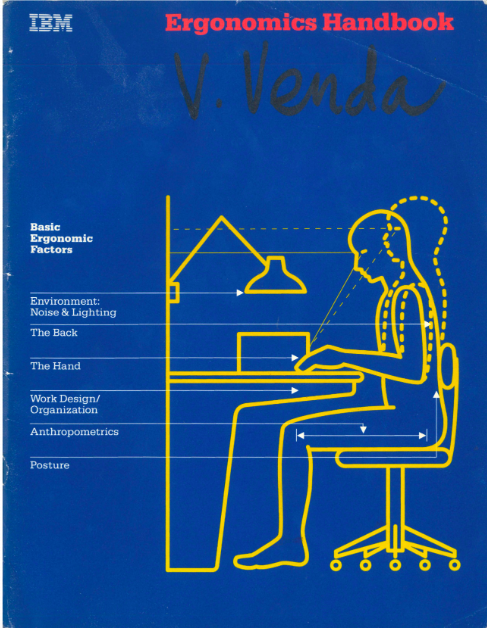

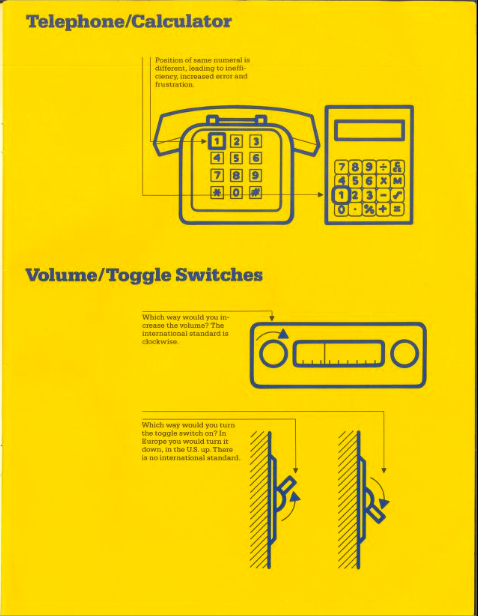

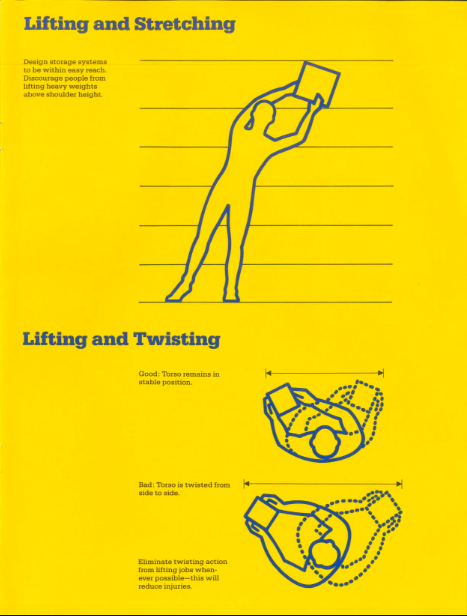

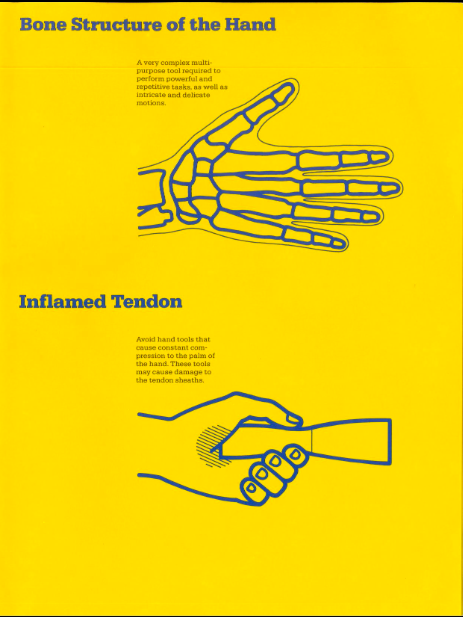

The IBM Ergonomics Handbook from 1989 addresses an evergreen topic. Office managers, physical therapists, and digital nomads should take note. Its recommendations on configuring the work space for maximum efficiency, productivity and employee comfort are solid. It’s not this handsome little yellow and blue employee manual’s fault that references to now-obsolete technology render it a bit quaint:

Think of two fairly recent innovations in our lives – the push button telephone and the pocket calculator. Both have a standard key set layout, but not the same layout.

Marier elected to let each pick be represented by its covers, figuring “what better way to browse designed objects than by how they look.”

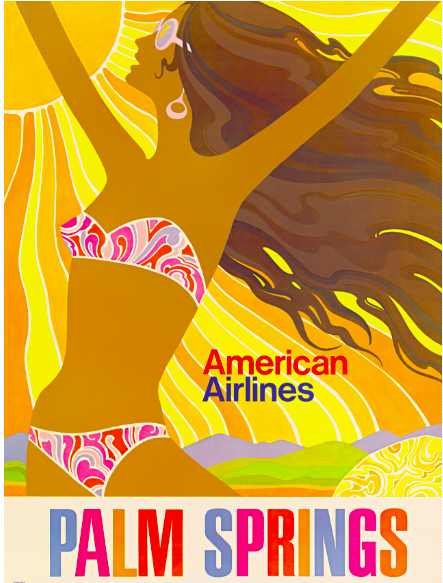

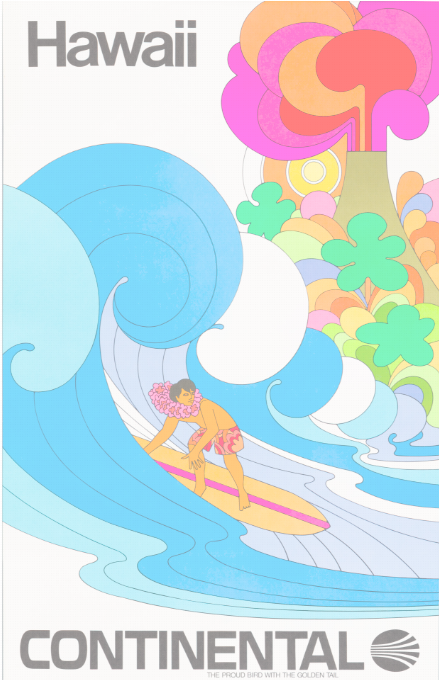

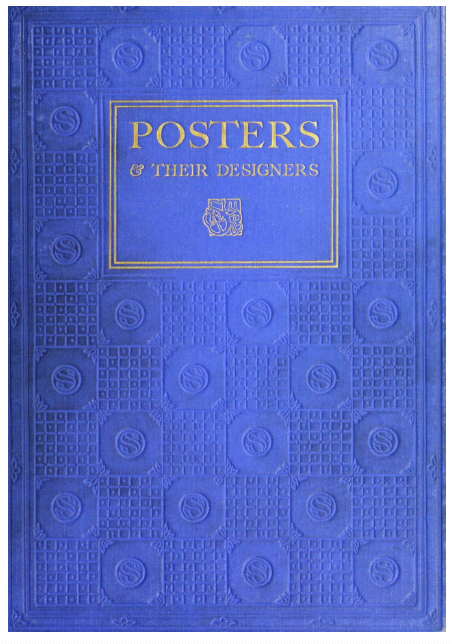

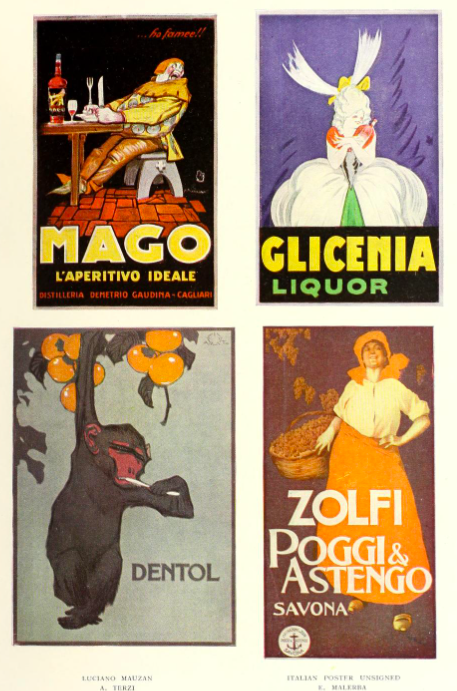

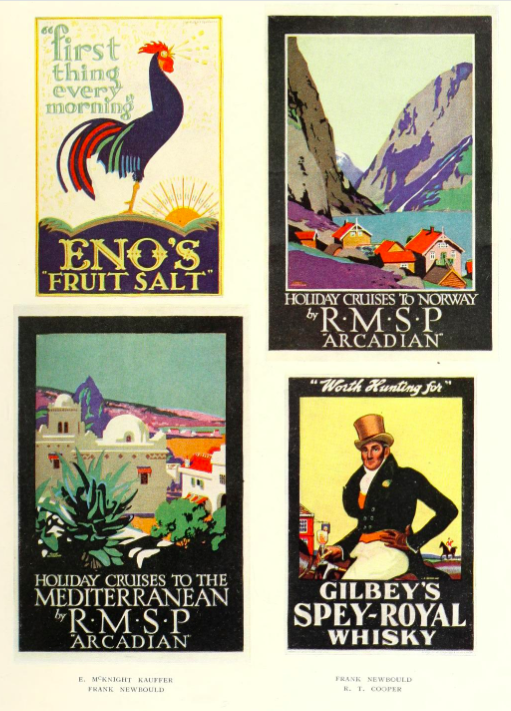

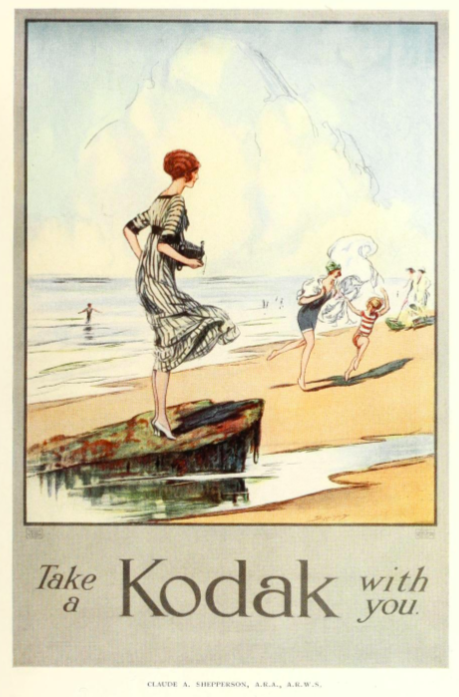

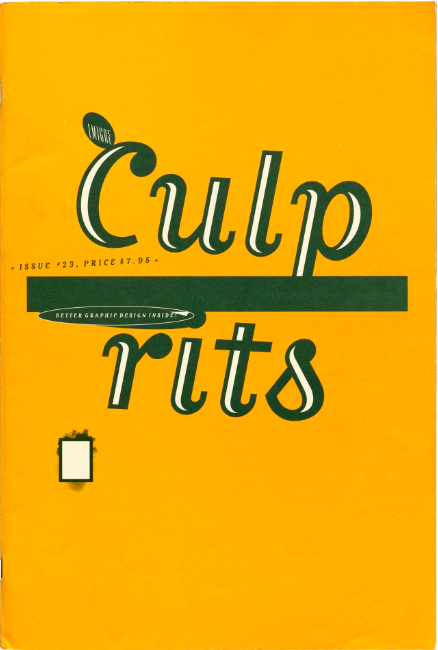

We agree, though we’re worried about where this might leave 1924’s Posters & Their Designers. How can its staid blue cover compete against its sexy neighbors in the posters category?

Small business owners, set dressers and public domain fans should give Posters & Their Designers a chance. Behind that discreet blue cover are a wide assortment of stunning early 20th century posters, including some full color reproductions.

While not specifically typography related, Marier wisely gives this resource a typography tag. Hand lettering loyalists and font fanatics will find much to admire.

We hope to pique your interest with a few more of our favorite covers, below. Begin your explorations of archives.design here.

Related Content

The Letterform Archive Launches a New Online Archive of Graphic Design, Featuring 9,000 Hi-Fi Images

Download 2,000 Magnificent Turn-of-the-Century Art Posters, Courtesy of the New York Public Library

40 Years of Saul Bass’ Groundbreaking Title Sequences in One Compilation

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

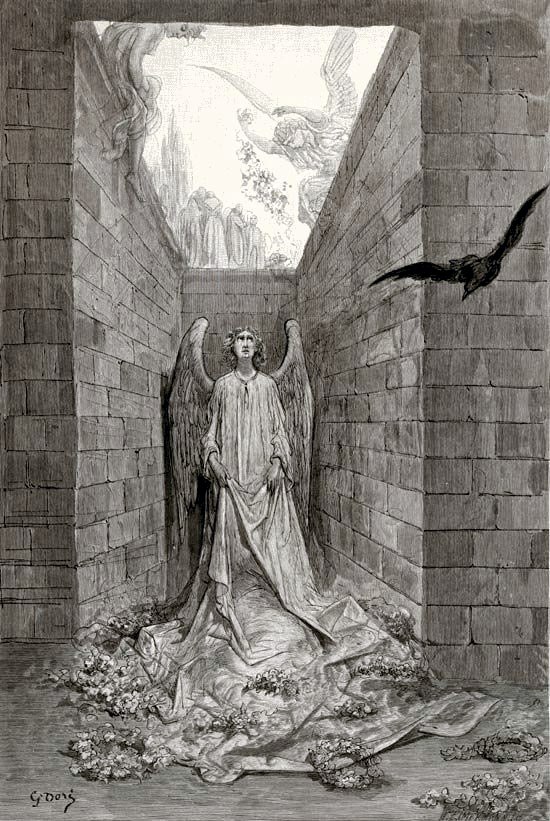

One of the busiest, most in-demand artists of the 19th century, Gustave Doré made his name illustrating works by such authors as Rabelais, Balzac, Milton, and Dante. In the 1860s, he created one of the most memorable and popular illustrated editions of Cervantes’ Don Quixote, while at the same time completing a set of engravings for an 1866 English Bible. He probably could have stopped there and assured his place in posterity, but he would go on to illustrate an 1872 guide to London, a new edition of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner, and several more hugely popular works.

In 1884, Doré produced 26 steel engravings for an illustrated edition of Edgar Allan Poe’s gloomy classic “The Raven.” Like all of his illustrations, the images are rich with detail, yet in contrast to his earlier work, particularly the fine lines of his Quixote, these engravings are softer, characterized by a deep chiaroscuro appropriate to the mood of the poem.

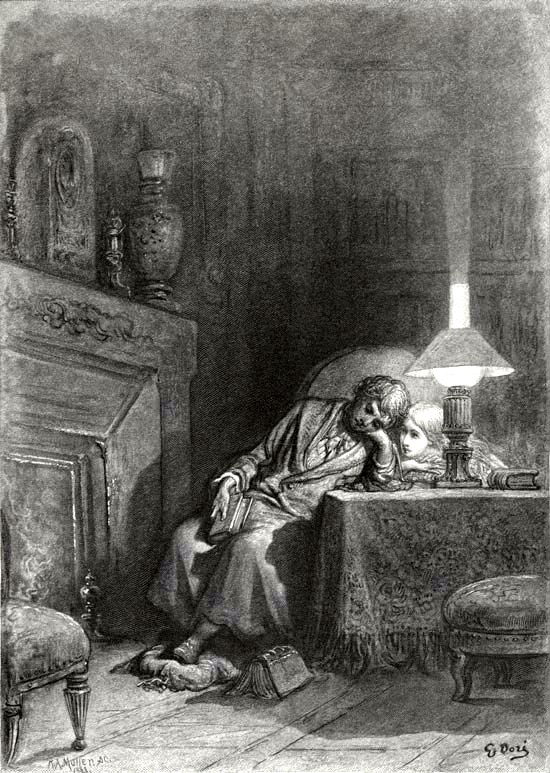

Above see the plate depicting the first lines of the poem, the haunted speaker, “weak and weary,” slumped over one of his many “quaint and curious volume[s] of forgotten lore.”

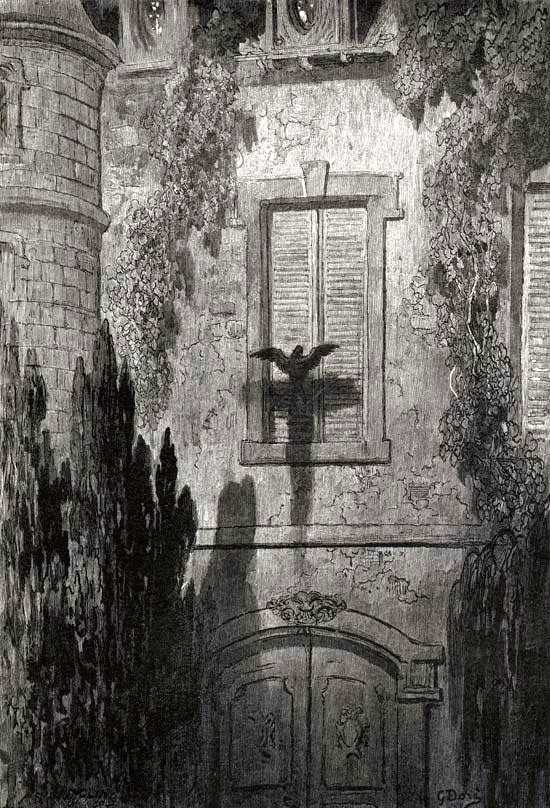

Below, see the raven tapping, “louder than before,” at the window lattice.

By the time Doré’s edition saw publication, Poe’s most famous work had already achieved recognition as one of the greatest American poems. Its author, however, had died over thirty years previous in near-poverty. A catalog description from a Penn State Library holding of one of Doré’s “Raven” editions compares the two artists:

The careers of these two men are fraught with both popular success and unmitigated disappointment. Doré enjoyed phenomenal monetary success as an illustrator in his life-time, however his true desire, to be acknowledged as a fine artist, was never realized. The critics of his day derided his abilities as an artist even as his popularity soared.

One might say that Poe suffered the opposite fate—recognized as a great artist in his lifetime, he never achieved financial stability. We learn from the Penn State Rare Collections library that Doré received the rough equivalent of $140,000 for his illustrated edition of “The Raven.” Poe, on the other hand, was paid approximately nine dollars for his most famous poem.

Project Gutenberg has digital editions of the complete Doré edition of “The Raven,” as does the Library of Congress.

Related Content:

The Raven: a Pop-up Book Brings Edgar Allan Poe’s Classic Supernatural Poem to 3D Paper Life

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Here on Open Culture, we’ve often featured the work of gallerist-Youtuber James Payne, creator of the channel Great Art Explained. Not long ago we wrote up his examination of the work of René Magritte, the Belgian surrealist painter responsible for such enduring images as Le fils de l’homme, or The Son of Man. Payne uses that famous image of a bowler-hatted everyman whose face is covered by a green apple again in the video above, but this time to represent a literary character: Leopold Bloom, the protagonist of James Joyce’s Ulysses. It is that much-scrutinized literary masterwork Payne has taken as his subject for his new channel, Great Books Explained.

Indeed, few great books are regarded as needing as much explanation as Ulysses. It was once described, Payne reminds us, as “spiritually offensive, anarchic, and obscene,” yet “in the hundred years since, the book has triumphed over criticism and censorship to become one of the most highly regarded works of art in the twentieth century.”

The strength of both this acclaim and this condemnation still today inspires a mixture of curiosity and trepidation. But as Payne sees it, Ulysses is ultimately “a novel about wandering, and we as readers should feel free to wander around the book, dip in and out of episodes, read it out aloud, and let the words wash over us like music.” It’s also “an experimental work, often strange and sometimes shocking, but it is consistently witty, and packed with a tremendous sense of fun.”

That latter quality belies the seven years of literary labor Joyce put into the book, all of it distilled into the events of a single day in Dublin, June 16, 1904, as experienced by Bloom, an “ordinary advertising agent” and a Jew among Catholics; the “rebellious and misanthropic intellectual” Stephen Dedalus, Joyce’s alter-ego and the hero of his previous novel A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man; and Leopold’s “passionate, amorous, frank-speaking” wife Molly. (Payne represents Dedalus with Raoul Haussman’s The Art Critic and Molly with Hannah Höch’s Indian Dancer.) In this framework, Joyce delivers kaleidoscopic detail, from the quotidian to the mythological and the sexual to the scatological, all with a formal and linguistic bravado that has kept the reading experience of Ulysses fresh for 101 years and counting.

Related content:

James Joyce’s Ulysses: Download as a Free Audio Book & Free eBook

Why Should You Read James Joyce’s Ulysses?: A New TED-ED Animation Makes the Case

Everything You Need to Enjoy Reading James Joyce’s Ulysses on Bloomsday

The Very First Reviews of James Joyce’s Ulysses: “A Work of High Genius” (1922)

Read the Original Serialized Edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses (1918)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

POWERFUL IMMIGRANT STORIES – IBBY AUSTRALIA’S SELECTIONS FOR INCLUSION IN THE HONOUR LIST 2024

IBBY Australia announces its selection of two extraordinary books to be included in the prestigious biennial IBBY Honour List for 2024.

These books become Australia’s representatives in a travelling exhibition of international titles. The 2024 exhibition will be featured at the IBBY Congress in Trieste, Italy, August 2024, the Frankfurt Book Fair, October 2024, the Bologna Children’s Book Fair 2025, and in many other travelling exhibitions to a variety of countries.

Each of the two books selected this year, powerfully reflect the experiences of immigrants to Australia.

This beautifully crafted novel explores the experiences of Asian immigrants to Australia with wit and authenticity. Wen Zhou is dealing with her father’s overbearing control of their family; helping her friend Henry Xiao develop his English skills; and planning to apply with him for a scholarship to a selective school. But when tragedy strikes the Xiao family, Wen and her mother defy Wen’s father by supporting them.

References to Confucius and other Chinese writers denote philosophical tenets and morals explored in this deeply personal narrative of how Wen seeks to reconcile parental expectations with her contemporary Australian social milieu. Details carry thematic weight, eg. Wen’s mother’s tailored, mended suits present a brittle veneer, camouflaging emotional tensions at home, and her cooking for the Xiaos denotes solace. Heavy themes are explored, such as emotional abuse, mental illness, and grief, but there’s also a lightness to the writing, infused with Wen’s quiet wisdom. Readers are left with the promise that two families have taken steps towards healing, and that for Wen and Henry, all will be well.

Rebecca Lim is an award-winning writer, illustrator and editor and the author of over twenty books, including Tiger Daughter (a CBCA Book of the Year: Older Readers and Victorian Premier’s Literary Award-winner), The Astrologer’s Daughter (A Kirkus Best Book and CBCA Notable Book) and the bestselling Mercy.

Her work has been shortlisted for the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards, NSW Premier’s Literary Awards, Queensland Literary Awards, Margaret and Colin Roderick Literary Award, Foreword INDIES Book of the Year Awards and Isinglass Award, shortlisted multiple times for the Aurealis Awards and Davitt Awards, and longlisted for the Gold Inky Award and David Gemmell Legend Award. Her novels have been translated into German, French, Turkish, Portuguese, Polish and Vietnamese. She co-founded the Voices from the Intersection initiative to support emerging YA and children’s authors and illustrators who are First Nations, People of Colour, LGBTIQA+ and/or living with disability, and co-edited Meet Me at the Intersection, a groundbreaking anthology of YA #OwnVoice memoir, poetry and fiction. Her latest novel is Two Sparrowhawks in a Lonely Sky (2023).

This is an expressive metaphorical exploration of the sacrifices made by immigrant parents for their children to flourish in a new country. The cover depicts a giant child dwarfing his parents; a postage stamp frames the title; endpapers depict teapots from several countries. Told as a fairy tale based on the trope of a bargain – sacrificing centimetres in height each time they give their child what he needs – this is a moving tribute to the parents’ selflessness.

The poetic line: ‘They had old shoes, and empty pockets’ resonates with meaning. The exquisite, muted artwork employs light, shade, and perspective to potent effect, and the metaphor of size is repeated, beginning with an iconic bonsai. Sworder’s inventiveness in format and approach, invested with emotional weight and power, speaks in any language. His technique employs graphite powder, pencils, watercolours, art paper, photo references, and digital technology, and was inspired by Japanese woodblock printmakers, Hokusai and Hiroshige. This universal and timeless story of hope and resilience is a gloriously eloquent paean to Sworder’s parents and to any immigrant.

Zeno Sworder is a Melbourne based writer, artist and picture book maker. He is passionate about literacy, creativity and diversity. He was born into a mixed (Chinese and English) multicultural family in regional Victoria and has worked as a window washer, a dish washer (a step up!), a journalist, an English language teacher, a volunteer for Lifeline, a consular officer and a tribunal advocate for migrants and refugees. But he has always felt most himself sitting at a table drawing pictures and making up stories.

His work has been published in The Age, Meanjin and recognised by the Australia Council for the Arts. His first book, This Small Blue Dot, has been described by the Children’s Book Council of Australia as ‘an example of an insightful contemporary work of art’ and won the CBCA Award for New Illustrator 2021 and Australian Book Design Awards Best Designed Children’s Illustrated Book 2021. My Strange Shrinking Parents won the CBCA Picture Book of the Year Award 2023.

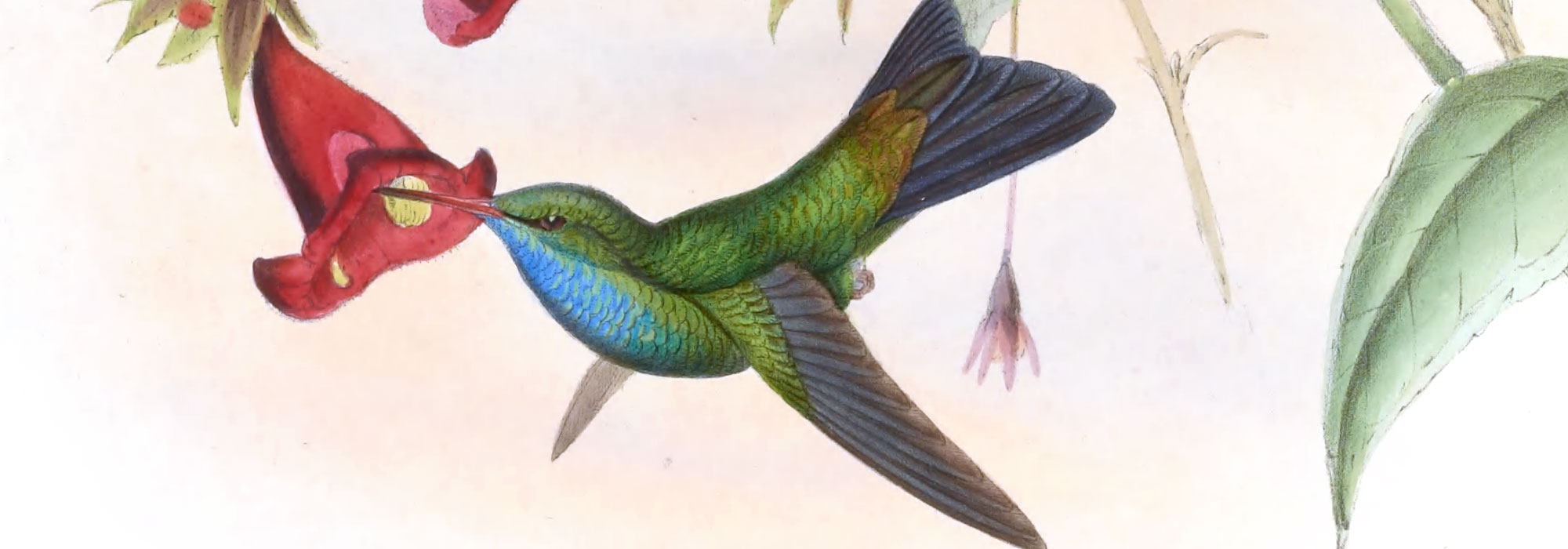

If you don’t live in a part of the world with a lot of hummingbirds, it’s easy to regard them as not quite of this earth. With their wide array of shimmering colors and frenetic yet eerily stable manner of flight, they can seem like quasi-fantastical creatures even to those who encounter them in reality. They certainly captured the imagination of English ornithologist John Gould, who between the years of 1849 and 1887 created A Monograph of the Trochilidæ, or Family of Humming-Birds, a catalog of all known species of hummingbird at the time. As you might expect, this is just the kind of old book you can peruse at the Internet Archive, but now there’s also an online restoration that returns Gould’s illustrations to their original glory.

A Monograph of the Trochilidæ “is considered one of the finest examples of ornithological illustration ever produced, as well as a scientific masterpiece,” writes the site’s creator, Nicholas Rougeux (previously featured here on Open Culture for his digital restorations of British & Exotic Mineralogy and Euclid’s Elements).

“Gould’s passion for hummingbirds led him to travel to various parts of the world, such as North America, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, to observe and collect specimens. He also received many specimens from other naturalists and collectors.” Taken together, the work’s five volumes — one of them published as a supplement years after his death — catalog 537 species, documenting their appearance with 418 hand-colored lithographic plates.

All these images were “analyzed and restored to their original vibrant colors in a process that took nearly 150 hours to complete. As much of the original plate was preserved — including the delicate colors of the scenic backgrounds in each vignette.” You can view and download them at the site’s illustrations page, where they come accompanied by Gould’s own text and classified according to the same scheme he originally used. You may not know your Phaëthornis from your Sphenoproctus, to say nothing of your Cyanomyia from your Smaragdochrysis, but after seeing these small wonders of the natural world as Gould did (all arranged into a chromatic spectrum by Rougeux to make a striking poster), you may well find yourself inspired to learn the differences — or at least to put a feeder outside your window.

via Kottke

Related content:

The Hummingbird Whisperer: Meet the UCLA Scientist Who Has Befriended 200 Hummingbirds

What Kind of Bird Is That?: A Free App From Cornell Will Give You the Answer

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

If those who have read Cal Newport’s Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World — and even more so, those who’ve been meaning to read it — share any one desire, it’s surely the desire to read more books. And for those who have reading habits similar to Newport’s, it wouldn’t actually have been a Herculean task to read more than 400 books over the past seven years since Deep Work‘s publication in 2016. Formidable though that total number may sound, it would only require reading about five books per month, and in the video above, a clip from his podcast Deep Questions, Newport explains his strategies for doing just that.

First, Newport recommends choosing “more interesting books”: that is to say, follow your own interests instead of asking, “What book is going to impress other people if they heard I read it?” Read a wide variety of books, changing up the genre, subject, and even format — paper versus audio, for example — every time. (For my part, I’d also recommend reading across several languages, matching the ambitions of your selected books to your skill level in each one.)

Then, schedule regular reading sessions: “Very few people tackle physical exercise with the mindset of, ‘If I have time and I’m in the mood, I’ll do it.’ As we know from long experience, that means you will do exactly zero hours of exercise. The same is true for reading.”

This hardly means you just have to grit your teeth and read. You can “put rituals around reading that make it more enjoyable”: Newport spends his Friday nights in his study with a book and a glass of bourbon, and in the summertime reads on his outdoor couch with a cup of coffee. Also satisfying is making the “closing push,” the final binge when “you’re at that last hundred pages, you have some momentum, you’ve been working on this book for a while, you can see the finish line.” But none of these strategies can have much of an effect if you don’t “take everything interesting off your phone.” Unlike most millennials, Newport has never participated in social media, with the positive side effect that reading books has become “my default activity when I don’t have something else to do.”

If you’d like to know more about how Newport, who’s also a father and a professor of computer science, fits reading into his life, have a look at his discussion of how to become a serious reader. This involves building a “training regime,” beginning with short spurts of whichever books you happen to find most exciting and working your way up to longer sessions with more complex reading material. He also has a video of advice for becoming a disciplined person in general, in which he employs his own specialized concepts, like identifying “deep life buckets” and, from them, drawing “keystone habits.” But as with so much in life, being disciplined in practice is a matter of identity. If you first “convince yourself that you are a disciplined person,” you’ll feel a constant, motivating need to live up to that label. In order to read more, then, declare yourself a reader: not just one who reads a lot, ideally, but one who reads well.

Related content:

Carl Sagan on the Importance of Choosing Wisely What You Read (Even If You Read a Book a Week)

Joseph Brodsky’s List of 83 Books You Should Read to Have an Intelligent Conversation

7 Tips for Reading More Books in a Year

800 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other Devices

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

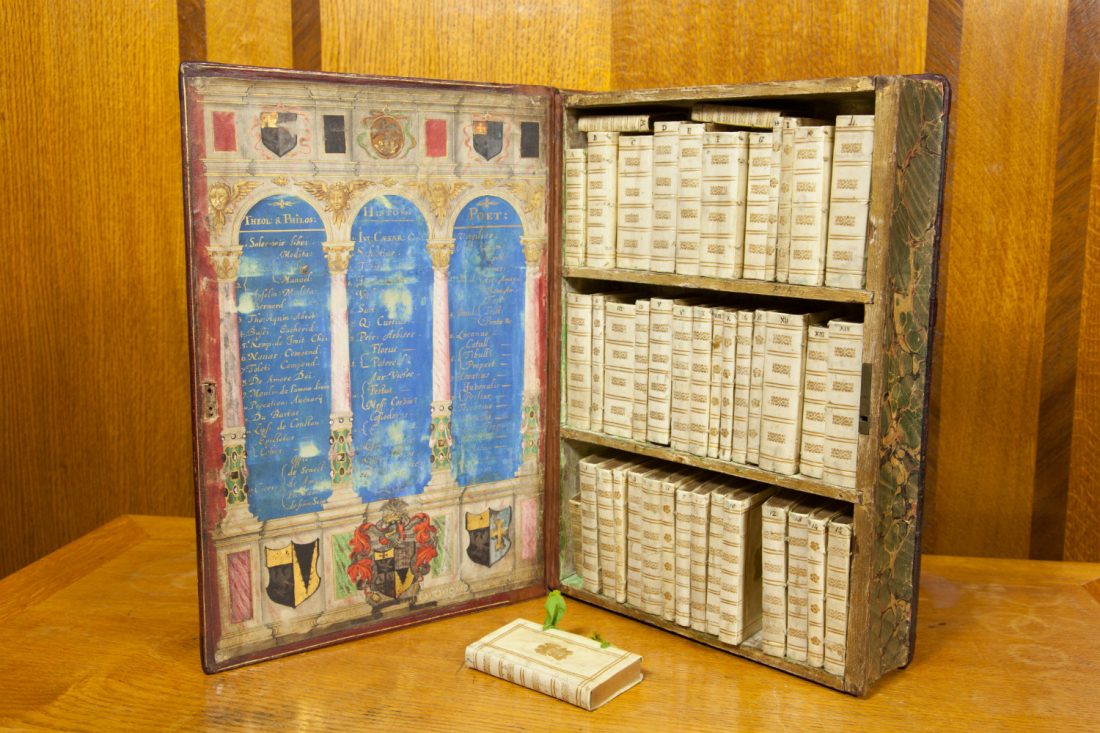

Image courtesy of the University at Leeds

In the striking image above, you can see an early experiment in making books portable–a 17th century precursor, if you will, to the modern day Kindle.

According to the library at the University of Leeds, this “Jacobean Travelling Library” dates back to 1617. That’s when William Hakewill, an English lawyer and MP, commissioned the miniature library–a big book, which itself holds 50 smaller books, all “bound in limp vellum covers with coloured fabric ties.” What books were in this portable library, meant to accompany noblemen on their journeys? Naturally the classics. Theology, philosophy, classical history and poetry. The works of Ovid, Seneca, Cicero, Virgil, Tacitus, and Saint Augustine. Many of the same texts that showed up in The Harvard Classics (now available online) three centuries later.

Apparently three other Jacobean Travelling Libraries were made. They now reside at the British Library, the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, and the Toledo Museum of Art in Toledo, Ohio.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Napoleon’s Kindle: See the Miniaturized Traveling Library He Took on Military Campaigns

The Harvard Classics: Download All 51 Volumes as Free eBooks

The Fiske Reading Machine: The 1920s Precursor to the Kindle

In high school, the language I most fell in love with happened to be a dead one: Latin. Sure, it’s spoken at the Vatican, and when I first began to study the tongue of Virgil and Catullus, friends joked that I could only use it if I moved to Rome. Tempting, but church Latin barely resembles the classical written language, a highly formal grammar full of symmetries and puzzles. You don’t speak classical Latin; you solve it, labor over it, and gloat, to no one in particular, when you’ve rendered it somewhat intelligible. Given that the study of an ancient language is rarely a conversational art, it can sometimes feel a little alienating.

And so you might imagine how pleased I was to discover what looked like classical Latin in the real world: the text known to designers around the globe as “Lorem Ipsum,” also called “filler text” and (erroneously) “Greek copy.”

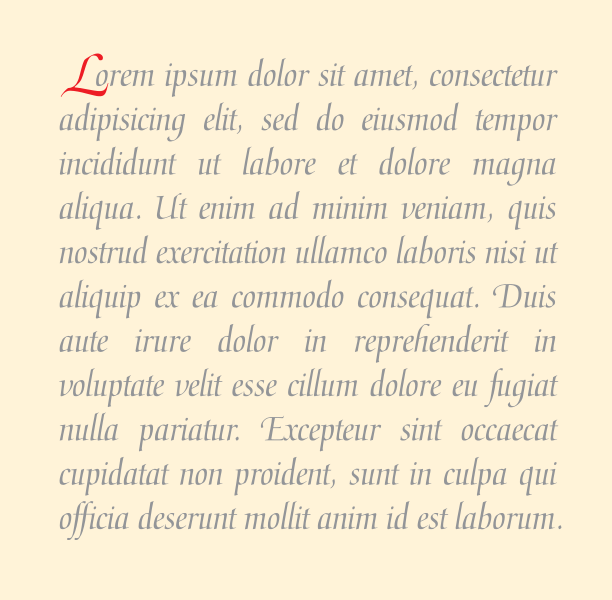

The idea, Priceonomics informs us, is to force people to look at the layout and font, not read the words. Also, “nobody would mistake it for their native language,” therefore Lorem Ipsum is “less likely than other filler text to be mistaken for final copy and published by accident.” If you’ve done any web design, you’ve probably seen it, looking something like this:

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

When I first encountered this text, I did what any Latin geek will—set about trying to translate it. But it wasn’t long before I realized that Lorem Ipsum is mostly gibberish, a garbling of Latin that makes no real sense. The first word, “Lorem,” isn’t even a word; instead it’s a piece of the word “dolorem,” meaning pain, suffering, or sorrow. So where did this mash-up of Latin-like syntax come from, and how did it get so scrambled? First, the source of Lorem Ipsum—tracked down by Hampden-Sydney Director of Publications Richard McClintock—is Roman lawyer, statesmen, and philosopher Cicero, from an essay called “On the Extremes of Good and Evil,” or De Finibus Bonorum et Malorum.

Why Cicero? Put most simply, writes Priceonomics, “for a long time, Cicero was everywhere.” His fame as the most skilled of Roman rhetoricians meant that his writing became the benchmark for prose in Latin, the standard European language of the Middle Ages. The passage that generated Lorem Ipsum translates in part to a sentiment Latinists will well understand:

Nor is there anyone who loves or pursues or desires to obtain pain of itself, because it is pain, but occasionally circumstances occur in which toil and pain can procure him some great pleasure.

Dolorem Ipsum, “pain in and of itself,” sums up the tortuous feeling of trying to render some of Cicero’s complex, verbose sentences into English. Doing so with tolerable proficiency is, for some of us, “great pleasure” indeed.

But how did Cicero, that master stylist, come to be so badly manhandled as to be nearly unrecognizable? Lorem Ipsum has a history that long predates online content management. It has been used as filler text since the sixteenth century when—as McClintock theorized—“some typesetter had to make a type specimen book, to demo different fonts” and decided that “the text should be insensible, so as not to distract from the page’s graphical features.” It appears that this enterprising craftsman snatched up a page of Cicero he had lying around and turned it into nonsense. The text, says McClintock, “has survived not only four centuries of letter-by-letter resetting but even the leap into electronic typesetting, essentially unchanged.”

The story of Lorem Ipsum is a fascinating one—if you’re into that kind of thing—but its longevity raises a further question: should we still be using it at all, this mangling of a dead language, in a medium as vital and dynamic as web publishing, where “content” refers to hundreds of design elements besides font. Is Lorem Ipsum a quaint piece of nostalgia that’s outlived its usefulness? In answer, you may wish to read Karen McGrane’s spirited defense of the practice. Or, if you feel it’s time to let the garbled Latin go the way of manual typesetting machines, consider perhaps as an alternative “Nietzsche Ipsum,” which generates random paragraphs of mostly verb-less, incoherent Nietzsche-like text, in English. Hey, at least it looks like a real language.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2015.

Related Content:

Why Learn Latin?: 5 Videos Make a Compelling Case That the “Dead Language” Is an “Eternal Language”

What Ancient Latin Sounded Like, And How We Know It

Can Modern-Day Italians Understand Latin? A Youtuber Puts It to the Test on the Streets of Rome

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

The IBBY Australia Ena Noël Award (Encouragement Award for Children’s Literature) has been presented from 1994 to 2022 to either a young developing Australian writer or illustrator.

In 2024, to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of the award’s inception, IBBY Australia Committee announces a change, in that two biennial awards will be presented – one to an author and one to an illustrator.

Guidelines for entry and entry forms for publishers are available on the awards page

The IBBY Australia Ena Noël Award (Encouragement Award for Children’s Literature) has been presented from 1994 to 2022 to either a young developing Australian writer or illustrator.

In 2024, to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of the award’s inception, IBBY Australia Committee announces a change, in that two biennial awards will be presented – one to an author and one to an illustrator.

Guidelines for entry and entry forms for publishers are available on the awards page

Hand binding a book, using primarily 15-century methods and materials sounds like a major undertaking, rife with pitfalls and frustration.

A far more relaxing activity is watching Four Keys Book Arts’ wordless, 24-minute highlights reel of self-taught bookbinder Dennis tackling that same assignment, above. (Bonus – it’s a guaranteed treat for those prone to autonomous sensory meridian response tingles.)

Dennis, whose other recent forays into bespoke bookbinding include a number of elegant matchbox sized volumes and upcycling three Dungeons & Dragons rulebooks into a tome bound in vegetable tanned goatskin, labored on the late-medieval Gothic reproduction for over 60 hours.

For research on this type of binding, he turned to book designer J.A. Szirmai’s The Archaeology of Medieval Bookbinding, and while the goal was never 100% period accuracy, Dennis notes that the craft of traditional hand-binding has remained virtually unchanged for centuries:

The medieval binder would have found many of the tools and techniques to be very familiar. The single biggest anachronism is my use of synthetic PVA glue rather than period-appropriate animal glue. The second historic anomaly is my use of marbled paper, though it could be argued that the earliest European marbled papers of the mid-17th century do overlap with this binding style. The nonpareil pattern I have chosen for the endpapers, though, dates from the 1820’s, and so is distinctly out of place. But apart from those, virtually all of the other materials in this book would have been available to the medieval bookbinder.

Those craving a more step-by-step explanation should set time aside to view the longer videos, below, in which Dennis shares such time-consuming, detail-oriented tasks as trimming and tidying the edges with a cabinet scraper and bookbinder’s plough, sewing endbands to support and protect the book’s head and the spine, and decorating the leather cover with a hand-tooled floral pattern embellished with gold foil highlights.

Rather than cut corners, he literally cuts corners – the metal clasp and corner guards – from a .8mm thick sheet of brass.

Only the final video is narrated, so be sure to activate closed captioning / subtitles in the YouTube toolbar to read his commentary.

Materials and tools used in this project:

Text Paper: Fabriano Accademia 120 gsm drawing paper, 65 x 50 cm, long grain

Endpapers: Four Keys Book Arts handmade marbled paper, Fabriano Accademia 120 gsm drawing paper, red handmade paper

Thread: Undyed Linen 25/3, unknown brand

Cords: Leather, unknown type, roughly 3 oz/ 1 mm

Wax: Natural Beeswax

Glue: Mix of Acid-Free PVA and Methyl Cellulose, 3:2 ratio.

Paper Knife (made from an old kitchen knife)

Bone Folder (handmade in-house)

Scrap book board, various sizes/thickness

Pressing Boards (1/2″ maple plywood, made in house)

Cast-Iron Book Press (Patrick Ritchie, Edinburgh, circa 1850)

Stainless Steel rulers, various sizes

Small Stanley Knife

Maple Laying Press (handmade in-house)

Small Carpenter’s Square, unknown brand

Pencil (Blackwing)

Steel dividers, unknown brand

Lithography Stone (circa 1925)

Cotton Rag

Agate Burnisher

Piercing Cradle (handmade in-house)

Awl

2″ natural bristle brush, generic

parchment release paper

blotting paper

Acetate barrier sheets, .01 gauge

Dahle Vantage 12e Guillotine (found at a thrift store)

Scissors

Bookbinding Needles

Sewing Frame (handmade in-house)

Brass H-Keys (handmade in-house)

Linen sewing tapes, 12 mm

Pins

Watch a full playlist of Four Keys Book Arts’ Medieval Gothic Binding videos here. See more of Dennis book binding projects on Four Keys Book Arts’ Instagram.

Related Content

Wonderfully Weird & Ingenious Medieval Books

When Medieval Manuscripts Were Recycled & Used to Make the First Printed Books

The Medieval Masterpiece, the Book of Kells, Has Been Digitized and Put Online

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.